We spend a significant amount of time explaining to investors our process for entering and exiting investments. We call this process technical research.

The technical process for entering and exiting positions occurs once a stock has met our fundamental criteria and gives us a framework on how best to enter and exit a position.

Technical research is based largely on the “psychology of the market” or the “psychology of a particular stock”. The process is designed to eliminate as much emotion as possible from the investment process.

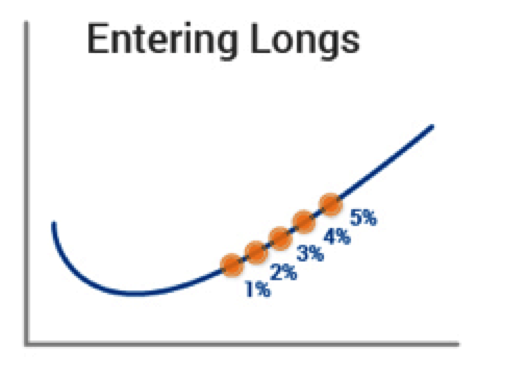

Scaling into a position

Diagram 1 (below) illustrates how we purchase a stock that we think is fundamentally cheap. We commence by adding a 1 per cent position (1 per cent of our portfolio value). We will only commence buying a 1 per cent position once a stock has finished falling and is rising in price.

There is a lot of emotion and psychology contained even in this initial 1 per cent purchase. If this stock is fundamentally cheap, how did it get cheap? Market participants must have been selling it. Why would they be selling a fundamentally cheap stock?

Why did some stocks during the global financial crisis halve in value despite earnings actually going up? Was it based on fundamentals or psychology or the most important of emotions, fear?

The other important point to note is that any initial position is only a 1 per cent position, that is, we are not “betting the farm”. And if we are wrong, we simply sell the position and take a small loss.

This means that each investment decision is not a life and death decision but merely part of an established process.

Diagram 1: Purchasing a fundamentally-cheap stock

Diagram 1: Entering Longs

We do not add to an initial 1 per cent position unless the stock price is going up. We add to our positions in 1 per cent increments and never add to the position if it falls in price. More often than not, potential investors who pride themselves on being deeply fundamental investors challenge this approach.

Common questions are: If you liked it at $1, don’t you like it more at $0.90? Actually no, we have already lost over 10 per cent on the first position and do not want to throw good money after bad.

What if the fundamentals we have evaluated are wrong? Then we would simply be adding to the size of a position that is already going against us.

Another common emotional state is that “you never go broke taking a profit,” so instead of adding another 1 per cent to a position that has gone up in value, why not just sell the first 1 per cent for a profit?

The answer is that while you cannot go broke making a 5 per cent or 10 per cent profit on a 1 per cent position, you will never make much either and you will not be around to benefit if the stock doubles, triples, quadruples or goes up tenfold (what Peter Lynch calls “ten-baggers” in his book One Up On Wall Street).

We add an additional 1 per cent to positions as a stock increases in price up to a maximum of 5 per cent exposure (at cost). In this way, we accumulate a 5 per cent position which is a “winning” position, that is, we could only have accumulated a 5 per cent position if the initial position was purchased at lower prices. In this way, we add to our winning positions and become more relaxed as our profit in the position grows.

Some investors I talk to agree to take an initial 1 per cent position at $1.00 but will then add to the position if it falls to 90 cents and then add to it again at, say, 80 cents.

What an emotional rollercoaster it must be. You have made an investment, you add to a losing position, now you are losing twice as much money on the same position and the best solution you can come up with is to add further to a losing position.

Now you have a 3 per cent position losing even more money, and where does this logic end? How often can you add to a losing position and how much pain can you bear.

And once you have added to a losing position several times, how well equipped are you emotionally to admit you have made a mistake, and at what cost? This is simply not a methodology we implement within our strategy.

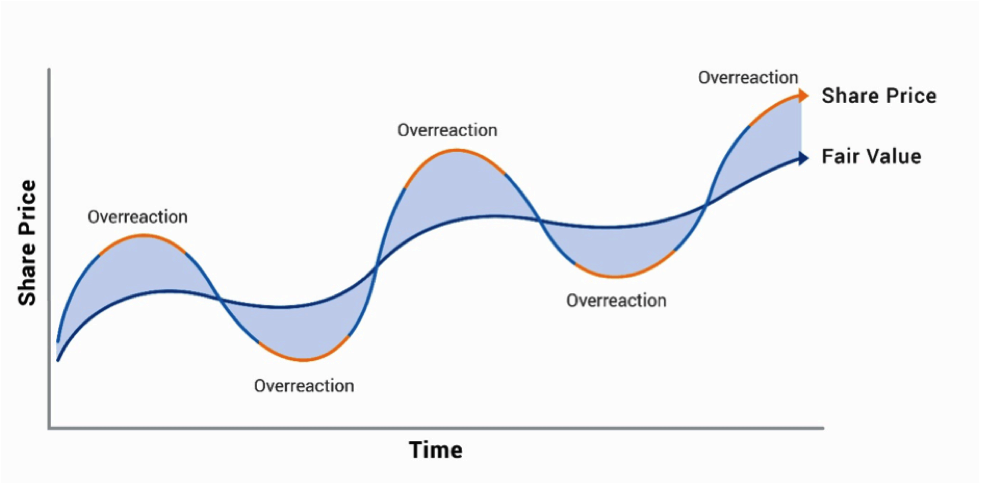

Why do share prices overreact?

Turing to Diagram 2 (below), we see that stocks move well beyond their fundamental value and I am sure we have all experienced incidences where stocks have moved significantly higher or lower than what we might deem their fundamental value.

Diagram 2: Share price overreactions

Diagram 2: Share price overreactions

Share price overreactions

Why does this happen? Jesse Livermore gives three main reasons for this phenomenon in his book Reminiscences of a Stock Operator — hope, fear and greed! These three emotions affect the psychology of the market or a particular stock.

We experience these emotions despite what the fundamentals are saying. Remember the very point at which you need to rely on your fundamentals is the very same point when you start to doubt your fundamentals.

(It is important to note at this stage that the phrase “fundamental analysis” is generally incorrectly used. These so-called fundamentals are in fact future earnings estimates for a particular company, which are at best informed guesses and at worst pure pie in the sky fabrications.)

We start to doubt our future earnings estimates (that is, act emotionally) at the very moment we need to rely on them.

We see time and time again the huge role psychology plays in investment and to suggest that psychology does not play an important role is to invest in a bubble.

We believe that an investor’s fundamental investment process has to be adapted to take account of psychology and in our case this involves a disciplined approach to entering and exiting fundamental positions.

Generally speaking, stock prices tend to move up on good news and earnings growth, and down on poor news and poor earnings growth. As outlined above these moves tend to “overshoot” in each direction.

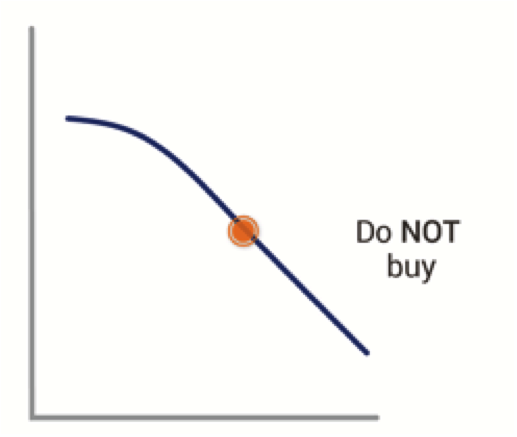

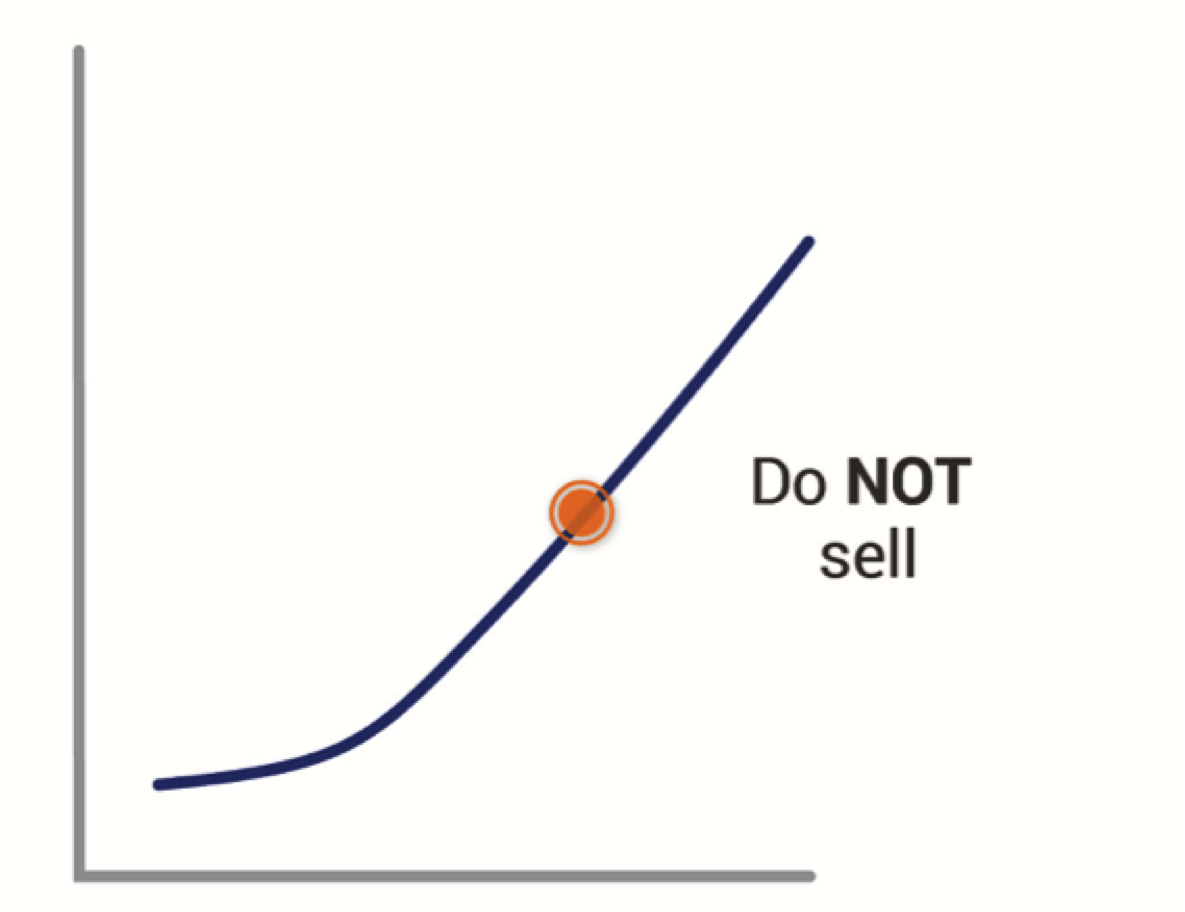

The diagrams below illustrate two basic rules that prevent an investor making very common emotional mistakes in the market and should help prevent buying or selling into an overreacting market.

Two simple, but very important, rules.

Rule Number 1: Do not buy a falling stock

Why are investors attracted to buying falling stocks? Emotions. If it was cheap at higher prices it must be cheaper now. I want to pick the bottom and look like a hero. I fear missing out on getting the lowest price and may have to pay more if the price goes back up.

Rule Number 2: Do not sell a rising stock

Again, why would someone sell a rising stock? Emotions. The stock has doubled, so it must be expensive. I fear if I do not sell now the stock will fall again. If I lock in a profit after doubling my money I will be safe. The desire to lock in a profit and be safe is potentially one of the biggest investment mistakes we can make.

You would think these two simple rules — do not buy stocks that are falling and do not sell stocks that are going up — would be easy to follow. Rationally speaking, they are easy rules to follow but all the emotions tied up when trying to follow these rules prevent most people from being able to do so.

As always, we could write a book on this topic and many authors have. The main point to convey in this short editorial is that ignoring the psychology of the market is like investing in a bubble.

Furthermore, each investor should realise that with every buy and sell decision they make, they are bringing to the table a number of powerful and potentially destructive emotions.

Good investors should recognise these emotions when they are experiencing them and have processes to deal with them.