“Never trust money more than gold.” ― Toba Beta.

In today’s note, I’m reviewing the WGC’s latest gold publication, which examines the yellow metal’s enduring role as a strategic asset. To briefly summarise, gold has four fundamental roles in any portfolio:

1. a source of long-term returns

2. a diversifier that can mitigate losses in times of market stress

3. a liquid asset with no credit risk that has outperformed fiat currencies

4. a means to enhance overall portfolio performance.

Introduction

Gold is becoming more mainstream, as evidenced by the fact that since 2001 investment demand for gold worldwide has grown on average by 15% annually. This has been driven in part by the advent of new ways to access the gold market – such as physical gold-backed exchange-traded funds (ETFs) – but also by the expansion of the middle-class in Asia, as well as a renewed focus on effective risk management in the wake of the 2008 GFC.

For institutional investors too, gold is more relevant than ever. Whilst central banks in developed markets are moving to normalise monetary policies, leading to higher interest rates, investors could still feel the effects of quantitative easing and a prolonged period of low interest rates for years to come. These policies may have fundamentally altered what it means to manage portfolio risk and could extend the time needed to meet investment objectives.

In response, institutional investors have embraced alternatives to traditional assets such as stocks and bonds. The share of non-traditional assets among global pension funds has increased from 15% in 2007 to 25% in 2017. And in the US this figure is close to 30%.

Many investors are drawn to gold’s role as a diversifier, due to its low correlation to most mainstream assets and as a hedge against systemic risk and strong stock market pullbacks. Some use it as a store of wealth and as an inflation and currency hedge.

As a strategic asset, gold has historically improved the risk-adjusted returns of portfolios, delivering returns while reducing losses and providing liquidity to meet liabilities in times of market stress.

A Source of Returns

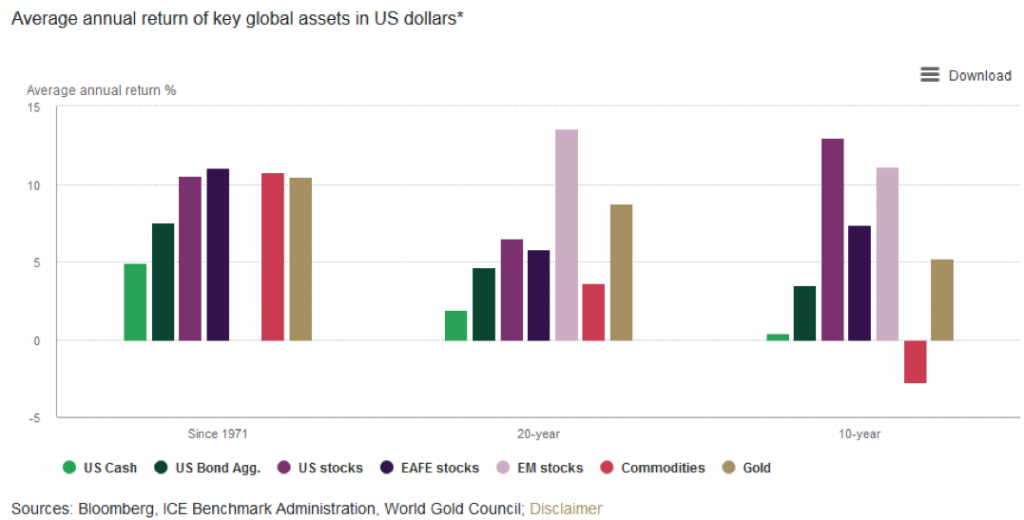

Gold is not only useful in periods of higher uncertainty. Its price has increased by an average of 10% annually since 1971, when gold began to be freely traded following the collapse of Bretton Woods. And gold’s long-term returns have been comparable to stocks and higher than bonds or commodities.

Chart 1: Gold has delivered positive returns over the long run, outperforming key asset classes

There is a good reason behind gold’s price performance – it trades in a large and liquid market, yet it is scarce. Mine production has increased by an average of 1.4% annually for the past 20 years. At the same time consumers, investors and central banks have all contributed to higher demand. On the consumer side, the combined share of global gold demand from India and China grew from 25% in the early 1990s to more than 50% in recent years.

WGC research shows that expansion of wealth is one of the most important drivers of gold demand over the long run. It has had a positive effect on jewellery, technology, and bar and coin demand – the latter in the form of long-term savings. Additionally, investors have embraced gold-backed ETFs and similar products to get exposure to gold. Gold-backed ETFs have amassed more than 2,400 tonnes (t) of gold worth US$100 billion since they were first launched in 2003.

And since 2010 central banks have been net buyers of gold in order to expand their foreign reserves as a means of diversification and safety.

Performance Well Above Inflation

During the period of the Gold Standard and subsequently the Bretton Woods system (when the US dollar was backed by and pegged to the price of gold), there was a close link between gold and US inflation. But once gold became free-floating, US inflation was not its main price driver.

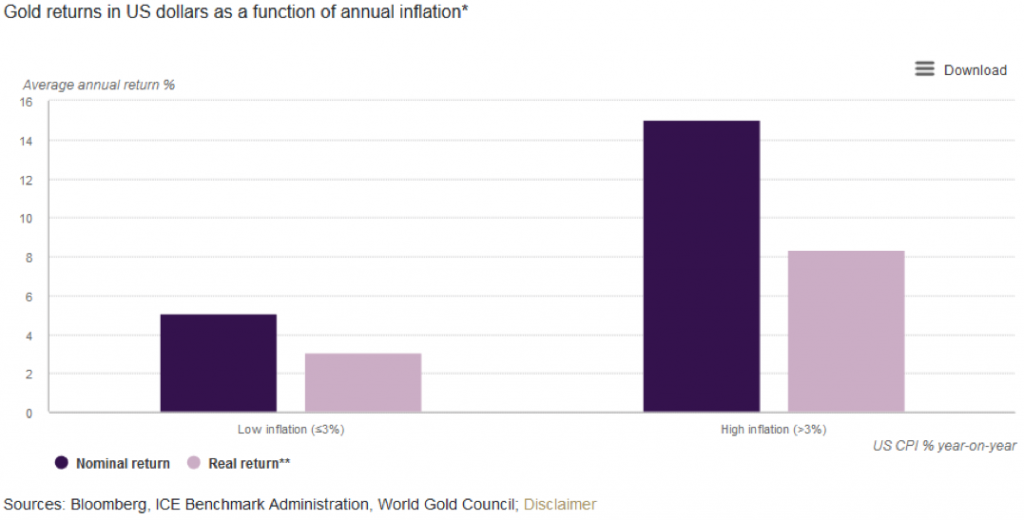

Sure enough, gold returns have outpaced the US consumer price index (CPI) over the long run, due to its many sources of demand. Gold has not just preserved capital, it has helped it grow. Gold has also protected investors against extreme inflation. In years when inflation has been higher than 3%, gold’s price has increased by 15% on average. Additionally, research by Oxford Economics shows that gold should do well in periods of deflation.

Chart 2: Gold has historically rallied in periods of high inflation

A High-Quality, Hard Currency

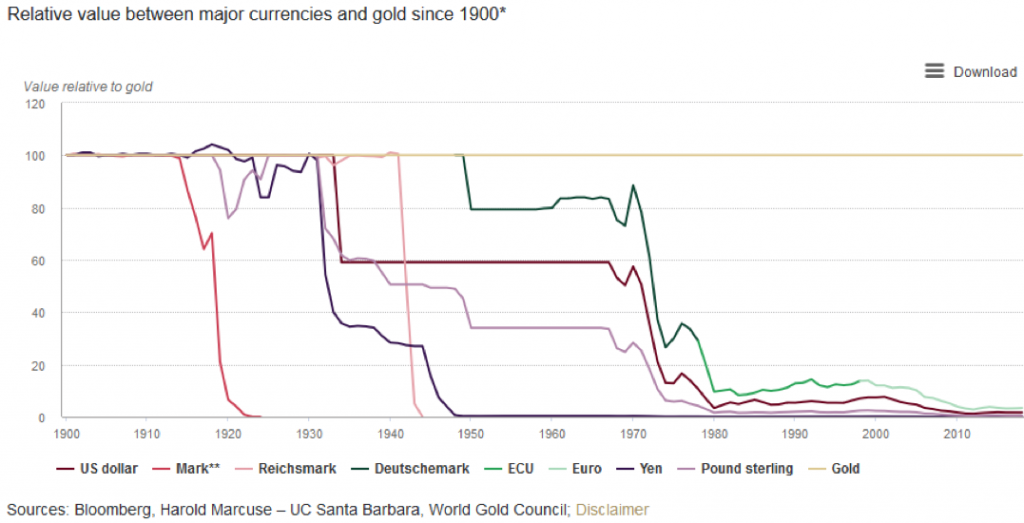

Over the past century, gold has greatly outperformed all major currencies as a means of exchange. This includes instances when major economies defaulted, sending their currencies spiralling downwards, as well as after the end of the Gold Standard. One of the reasons for this robust performance is that the available above-ground supply of gold has changed little over time – over the past two decades increasing by approximately 1.6% annually through mine production.

By contrast, fiat money can be printed in unlimited quantities to support monetary policies.

Chart 3: Gold has outperformed all major fiat currencies over time

Diversification that Works

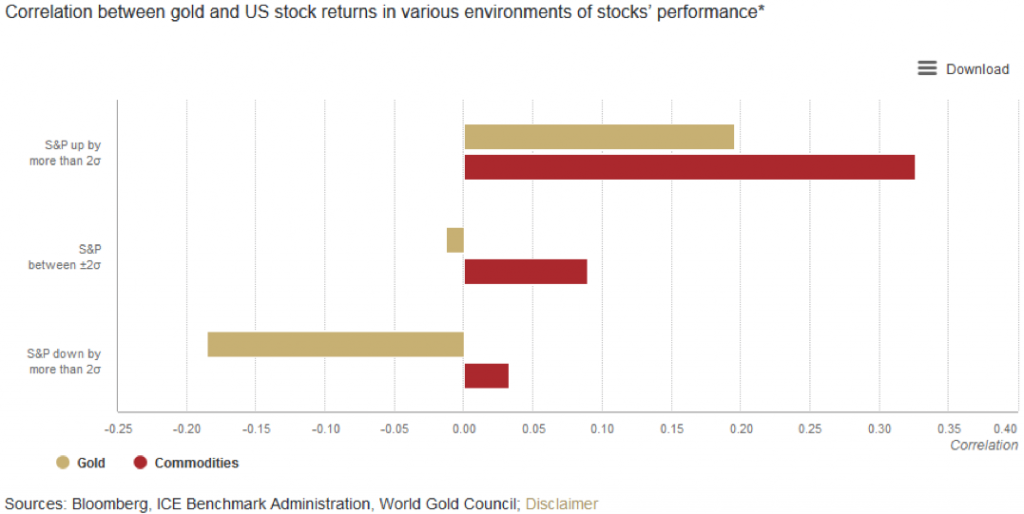

Although most investors agree about the relevance of diversification, effective diversifiers are not easy to find. Correlations tend to increase as market uncertainty (and volatility) rises, driven in part by risk-on/risk-off investment decisions. Consequently, many so-called diversifiers fail to protect portfolios when investors need it most.

For example, during the 2008–2009 financial crisis, hedge funds, broad commodities and real estate, long deemed portfolio diversifiers, sold off alongside stocks and other risk assets. This was not the case with gold.

Gold historically benefits from flight-to-quality inflows during periods of heightened risk. By providing positive returns and reducing portfolio losses, gold has been especially effective during times of systemic crisis, when investors tend to withdraw from stocks. Gold has also allowed investors to meet liabilities, while less liquid assets in their portfolio were undervalued and possibly mispriced.

In fact, the greater the downturn in stocks and other risk assets, the more negative gold’s correlation to these assets becomes.

But gold’s correlation doesn’t only work for investors during periods of turmoil. Due to its dual nature as a luxury good and an investment, gold’s long-term price trend is supported by income growth. As such, research shows that when stocks rally strongly their correlation to gold can increase, driven by the wealth effect and, sometimes, by higher inflation expectations.

Chart 4: Gold’s correlation with stocks helps portfolio diversification in good and bad economic times

Enhancing Portfolio Performance

The combination of all these factors means that adding gold to a portfolio can enhance risk-adjusted returns. Over the past decade, the WGC estimates that institutional investors with an asset allocation equivalent to the average US pension fund would have benefitted from including gold in their portfolio. Adding 2%, 5% or 10% in gold would have resulted in higher risk-adjusted returns.

Conclusion

What all of this tells us is that the arguments and incentives for holding gold are stronger than ever. It would surprise many to know that gold has increased in price by an average of 10% annually since 1971. Returns have also outpaced the US consumer price index (CPI) over the long run and during years when inflation has been above 3%, gold’s price has increased by 15% on average. Gold has also over the past century greatly outperformed all major currencies as a means of exchange. And unlike fiat money, which can be printed by governments in unlimited quantities to support monetary policies (think Venezuela and Zimbabwe in recent times), gold is in limited supply and therefore maintains its value.