“You have to choose (as a voter) between trusting to the natural stability of gold and the natural stability of the honesty and intelligence of the members of the Government. And, with due respect for these gentlemen, I advise you, as long as the Capitalist system lasts, to vote for gold.” — George Bernard Shaw.

We’ve witnessed an extraordinary breakout with respect to the price of gold over recent months. The yellow metal broke out above its critical level of technical resistance during the month of June, rising above the high reached during July 2016 of $1380 per ounce. Importantly too, it has managed to remain well above that level.

Gold’s robust performance has been driven by a confluence of factors – all positive – including falling interest rates, economic growth concerns, political instability, and uncertainty surrounding the ongoing trade war between the US and China. There have been other factors too, such as geopolitical concerns, including unrest in Hong Kong, as well as the recent attack on Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities.

After briefly touching the $1550 per ounce mark during early September, the gold price has since consolidated somewhat, which is entirely rational, but importantly has remained firmly above the $1450 per ounce level.

The bottom-line is that investors and traders have moved strongly towards gold, reinforcing its traditional role as a safe-haven during times of political and economic uncertainty.

A Rally that Began 20 Years Ago

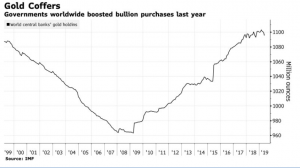

It can be argued that the bull market in gold began at the start of this century. Ironically, following the Bank of England’s decision to liquidate half of its gold reserves at prices as low as $250 per ounce, gold’s recovery began. This is a far cry from the days of the Bank of England and Australia’s Reserve Bank selling vast volumes of gold reserves, central banks around the world these days are net buyers of the metal, at price levels six times higher than where the Bank of England sold.

Central Bank Accumulation

Central-bank accumulation of bullion has emerged as an increasingly important trend in the global market, offering additional support for prices that have rallied to the highest level since 2013 on rising demand. Authorities have been adding to reserves as growth slows, trade and geopolitical tensions rise, and some nations seek to diversify away from the dollar. Official purchases now account for about 10% of worldwide consumption.

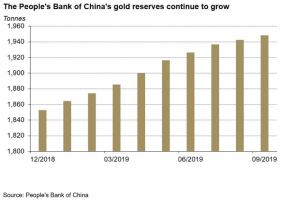

The Peoples’ Bank of China recently added a further 6 tons to its gold reserves during the month of September. This represents the tenth consecutive month of gold purchases, with the nation’s gold reserves now standing at 1,948t at the end of September. So far in 2019, China has added 95.8t of gold to its reserves.

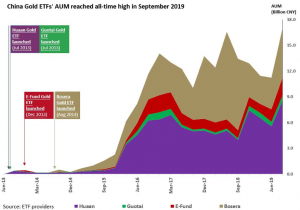

Meanwhile, the total Assets Under Management (AUM) of Chinese gold ETFs reached 17 billion yuan or US$2.4 billion as at the end of September, a new all-time record. As of 30th September, holdings of China’s four gold-backed ETFs’ totalled 50t, a 3.5t month-on-month rise. Chinese gold ETF investors tend to be more sophisticated and longer-term oriented, thus treating any dip in the gold price as an opportunity to expand their gold allocations.

In all, the world’s central banks added 374.1 tons to their holding during the first six months of 2019, helping push total bullion demand to a three-year high. The trend is expected to continue, with a recent survey of central banks showing 54% of respondents expect global holdings to climb in the next 12 months.

While the central banks of emerging nations have provided gold price support through their purchases, many of the central banks from the world’s biggest nations have provided gold price support through their policy actions – specifically debt.

Gold’s best friends remain the world’s debt-addicted central banks. What started out as a temporary post-GFC measure to try and avoid international economic catastrophe, has now morphed into a dangerous addiction. It has now become a seemingly-permanent means of keeping the international economic wheels turning on a day-to-day basis.

The Dangers of Perpetually Low-Interest Rates

Keeping rates low for several quarters is a very different situation from keeping them there for years. What has transpired is that the low-rates scenario has unintentionally punished savers and distorted market prices, in turn encouraging enormous and destabilizing financial speculation.

Furthermore, central bank policies of inducing negative real rates to effectively ‘incentivize’ borrowing has expanded the money supply and devalued currencies – in turn forcing investors to chase riskier assets in order to generate returns. It is little wonder therefore that investors are increasingly seeking refuge in gold.

Base interest rates in industrialised nations have remained low since the financial crisis of 2008. Frequently throughout this period the rate of inflation has been higher than this, implying a loss in spending power over time for each unit or currency.

In the USA, the August 2019 inflation reading showed that ‘core’ consumer prices (excluding volatile food and energy prices) rose to an 11-year high of 2.4% growth year-on-year. Not since September 2008 have prices expanded so fast and this doesn’t include the effects of the 15 tariffs on $112 billion in Chinese goods that the U.S. imposed on 1st September.

Conclusion

Gold’s robust recent performance has been driven by a confluence of factors – all positive. Right now, gold markets are in a consolidation phase following its strong run from below $1300 in June to a high of $1550.

One of the persistent arguments against owning gold is that it “does nothing.” Unlike cash that earns interest, gold is a non-yielding asset. However, in today’s world of close-to-zero and negative interest rates, the old-fashioned notion that favours holding cash over gold is increasingly defunct.

Encouragingly too, gold’s ascent has taken place against a background of US strength (typically a negative for the gold price), thanks in part to strong central bank buying. Gold is likely to continue to trade between $1450 and $1500 in the near-term.