One disappointment through 2019 was the lack of meaningful Chinese stimulus that appeared in the data. This leads to a host of questions: What exactly are we looking for in a growth rebound? Where could it show up first? What might it mean for global markets? And how does the evolving coronavirus outbreak impact this story?

Let’s begin with the last question. Markets sold off last month on concerns that the coronavirus poses a serious threat to the global economy. From what we know so far, the infection rate of the virus is well above that seen in SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), while the death rate is notably lower. The Chinese government has been more proactive in attempting to contain the virus, as compared to the SARS episode. While it’s still early on, and therefore hard to predict, we think that the virus poses a short-term risk to first-quarter growth in China. However, we also anticipate some catch-up in growth through the rest of the year.

What does a Chinese growth rebound look like?

What are we looking for in a rebound? We expect to see the Chinese economy stabilize at some point this year—with perhaps a slight acceleration in growth—but it’s important to note that we don’t expect the sort of rebound that was seen in 2016. Chinese government leaders have made it very clear that they will be maintaining a defensive easing bias, and we don’t expect them to drop this approach, given their desire to continue the pursuit of deleveraging in the economy. Nevertheless, this defensive easing and the recent pullback in trade tensions should be enough to stabilize and slightly boost growth.

We will also be closely looking for any improvement in the domestic consumption picture. Retail sales in China were generally disappointing through 2019. However, some perspective is useful here—notably, that retail growth rates have not fallen below 8% on a year-over-year basis. The timing of the virus outbreak, in the middle of Lunar New Year, will act as a drag on retail sales through the first half of the year, given the lower rates of tourism and movement around China.

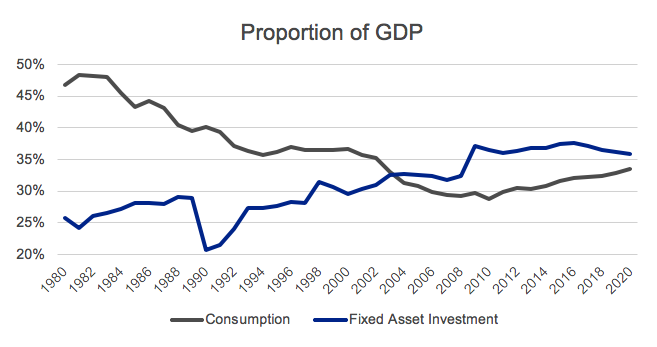

It’s worth reiterating the importance of the domestic consumption story, given the backdrop of an economy that is transitioning from capital/investment-led to consumption-led. Currently, consumption accounts for around 35% of gross domestic product (GDP) in China, compared to around 60% in most developed economies. As per capita income increases and the economy further develops, personal consumption will continue to increase, accompanied by a decline in the currently high saving rate.

Source for chart: Refinitiv Datastream, 31 Dec 2019

Where could growth improvements show up first?

There are three key data points that we are closely watching for signs of a growth resurgence: The manufacturing PMIs (purchasing managers’ indexes—particularly the forward-looking components, such as new orders), credit numbers and trade numbers. We have seen some tentative evidence in the PMIs that manufacturing has bottomed in the economy. The credit numbers remain fairly tepid and are unlikely to see a significant move higher given this deleveraging campaign. The trade numbers are pointing to a slight tick upward in domestic demand through imports and should benefit further as headwinds from the China-U.S. trade situation abate through the year.

Implications of the Phase 1 trade deal

The signing of the trade deal between the U.S. and China, and the subsequent easing of trade tensions, has been a positive development. We’ve already started to see signs of improvement in Chinese and Asian trade numbers, which is encouraging. However, it’s important to note that the level of purchases that the Chinese have agreed to over the next two years is quite significant—a $200 billion increase from 2017 levels.

This has two implications. First, it is unlikely that China will actually be able to achieve these levels over the next two years. This difficulty will be exacerbated if containment of the coronavirus is drawn out. We don’t see this as being a catalyst for a re-escalation of trade tensions this year, but it could have implications if President Trump is re-elected in November. Secondly, the increase in U.S. imports is going to require China to buy less from other regions (such as Europe for manufacturing, and South America for agriculture).

Potential market impact

So, what could a Chinese rebound mean for global markets? It would likely provide an additional shot in the arm for markets. Why? For starters, the outlook for the global economy in 2020 appears to be a bit better than expected, as risks around the trade war ease. Given that non-U.S. economies slowed the most in 2019, we expect that this year, these same economies will lead the way. In short, non-U.S. equity markets should see a bit of outperformance. We would also expect the U.S dollar to be a bit softer this year, as stronger non-U.S. fundamentals attract international capital flows into those economies and strengthen their currency versus the dollar.

The bottom line

The coronavirus outbreak has put the brakes on a Chinese growth rebound in the short-term, but assuming that the outbreak is contained, we expect a slight pickup in China’s year-over-year growth rate. Positive news on the trade front, an increase in personal consumption and tentative signs of a recovery in the manufacturing sector will likely provide a boost to China’s economy, and to global markets overall.