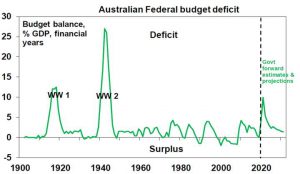

The Federal Government has updated its budget deficit projections and economic assumptions in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO). Thanks to a combination of stronger than expected economic growth and a higher than expected iron ore price, revenue growth has increased and projections for outlays have been lowered. As a result, the budget deficit for 2020-21 has been revised down to $197.7bn (or 9.9% of GDP) from $213.7bn just 10 weeks ago in the October Budget. This is still a record budget deficit, and as a share of GDP is still the largest since WW2. However, it’s likely that – providing we continue to keep coronavirus under control in Australia and vaccines become widely available through 2021 enabling a continuing recovery in the economy – we have now seen the peak in the budget deficit

Little new policy stimulus

This is the first major budget/fiscal policy announcement since March that has not seen significant new fiscal stimulus. There was a bit more on aged care and since the Budget, we have seen an extension of Coronavirus Supplement payments and additional vaccine funding – but it only amounts to additional stimulus of $4.9bn for this financial year in contrast to the extra stimulus of $159.8bn that had been announced up until the Budget. With the economy recovering faster than expected and the Government having announced an extra $41bn in stimulus mostly in or around October’s Budget, significant additional new stimulus is not required at this stage. Note that total fiscal stimulus since last December’s MYEFO now amounts to a massive $164.7bn for this financial year.

Economic growth revised up

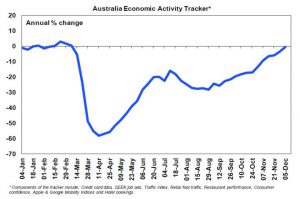

Since the Budget, the economy has recovered faster than expected – highlighted by a 3.3% rebound in September quarter GDP despite the Victorian lockdown. Stronger than expected data for confidence, employment, retail sales, car sales and housing related indicators suggests that this is continuing in the current quarter. In fact, our Australian Economic Activity Tracker (based on weekly data releases for things like restaurant and hotel bookings, credit and debit card transactions, mobility, job ads and confidence) is now back to around year ago levels, after being down 58% in April.

Source: AMP Capital.

Consistent with this, the Government has revised up its 2020-21 GDP growth forecast to +0.75% from -1.5% and has revised down its unemployment forecasts for the years ahead, with the peak now expected to be 7.5%, which is down from 8%. Based on November’s jobs data even this may be too pessimistic.

Source: Australian Treasury, AMP Capital

Budget deficit revised down a bit

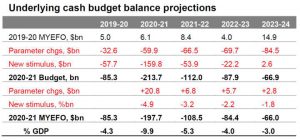

The Government’s revised budget projections are shown in the next table. Since the October Budget, the upgraded economic growth forecasts, along with a much higher than expected iron ore price, has seen revenue revised up and spending revised down (with for example 1.5 million jobs now subject to the reduced JobKeeper subsidy as opposed to an estimate at the time of the Budget of 2.2 million jobs). As a result, “parameter changes” (i.e. the impact on the budget of changed economic assumptions) have reduced the 2020-21 budget deficit by $20.8bn. With additional stimulus of just $4.9bn, this has seen this year’s budget deficit revised down to $197.7bn. This is still a record and at 9.9% of GDP is the highest since WW2.

However, the faster and earlier economic recovery and associated boost to revenue and reduction in spending projections has also seen the deficit revised down slightly for subsequent years. Note that the Government is still cautiously assuming that the iron ore price will fall back to $US55/tonne by the end of September next year, compared to the current price of around $US150/tonne, so if it continues to surprise on the upside, the budget deficit will be several billion dollars lower.

Source: Australian Treasury, AMP Capital

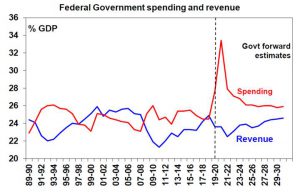

Assuming the economy continues to recover as forecast, we have now likely seen the peak in the budget deficit. Over the forward estimates to 2023-24, the deficit is still projected to fall rapidly as temporary support programs phase down, leading to a sharp decline in Government spending.

Source: Australian Treasury, AMP Capital

But it’s still going to be a long hard slog back to surplus, with the budget likely to remain in deficit for the next decade. Even if the post GFC “budget repair” experience is replicated, budget balance is unlikely until around 2032 and that is optimistic, as the GFC did less damage to the budget.

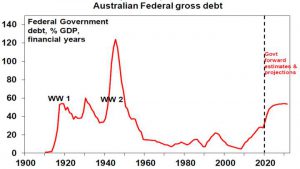

While productivity enhancing reforms will help grow the economy, it’s unlikely to be enough to achieve anything like the rapid post WW2 decline seen in the debt to GDP ratio. In fact, the Government is still projecting the debt to GDP ratio to head higher in the years ahead before peaking in the second half of the current decade at around 53% of GDP. The risk is that it could head even higher to around 70% of GDP early next decade, from around 35% of GDP now, or to nearly $2 trillion.

Source: Australian Treasury, AMP Capital

Source: Australian Treasury, AMP Capital

Assessment

The faster rebound in the economy and associated faster than expected recovery in jobs has taken some pressure off the budget and reduced the threat posed by the so-called fiscal cliff next year as direct income support and the bank payment holiday phase down. The fiscal cliff threat had already been reduced by the Government’s move to phase down support measures rather than abruptly end them but if the economy continues to recover as expected then their phasing down (as we already saw with JobKeeper and JobSeeker at the end of September) won’t pose a big threat to the economy as the economy will become less and less reliant on these support measures. For example, only 1.5 million jobs are now “protected” by JobKeeper which is well down from 3.6 million six months ago. High levels of pent up demand and saving also provide a big buffer here.

More broadly, notwithstanding the improvement seen in MYEFO, our assessment remains that the blow out in the budget deficit this year was appropriate and is affordable. Without the stimulus, the short term hit to businesses, jobs and incomes as well as the long-term scarring to workers would have been far greater, the recovery a lot slower and the budget deficit ultimately a lot worse. Moreover, the starting point for public debt in Australia is very low compared to many comparable countries, Australia is not borrowing in foreign currencies so does not run the risk of an old fashioned “foreign currency crisis” and public debt interest costs are very low.

Implications for Australian assets

The improved budget outlook, albeit marginal, is consistent with the faster than expected rebound so far in the economy. There is still a fair way to go but it should be supportive of Australian shares, the property market and the Australian dollar over the year ahead.