Introduction

It’s been more than a year since the RBA started using a range of unconventional monetary policies in response to the impact on the economy of the pandemic driven lockdowns and we are now seeing a strong recovery. Normally the RBA might now be starting to contemplate rate hikes for some time in the next year but their operating function is now very different to that seen prior to the pandemic.

RBA on hold again

As was widely expected, the RBA left monetary policy on hold at its April meeting. While again acknowledging that the global and Australian economies are recovering faster than expected the RBA reiterated that:

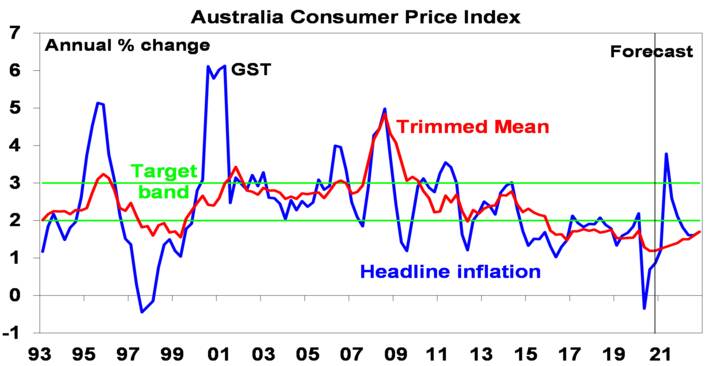

- it will not increase the cash rate from 0.1% until actual inflation is sustainably in the 2 to 3 percent target;

- this will require a much tighter jobs market and much stronger wages growth and these conditions are not expected to be met until 2024 at the earliest; and

- it’s still committed to the 0.1% 3-year bond yield target; and

- it noted that it is prepared to undertake further bond purchases beyond current programs if it would help.

Fortunately, the stabilisation in bond markets and some softening in the $A has taken some pressure off the RBA.

Strong recovery

While some sectors of the economy have lagged in the recovery – notably travel related and CBD services businesses reflecting the ongoing impact of the pandemic – spending and activity has diverted to other parts of the economy (eg, from CBD cafes to suburban cafes and from travel to spending on household goods) and the economy overall has seen a faster than expected recovery as evident in a range of indicators:

- As at December GDP had recovered 85% of its -7.3% slump to be just -1.1% below its pre-pandemic level.

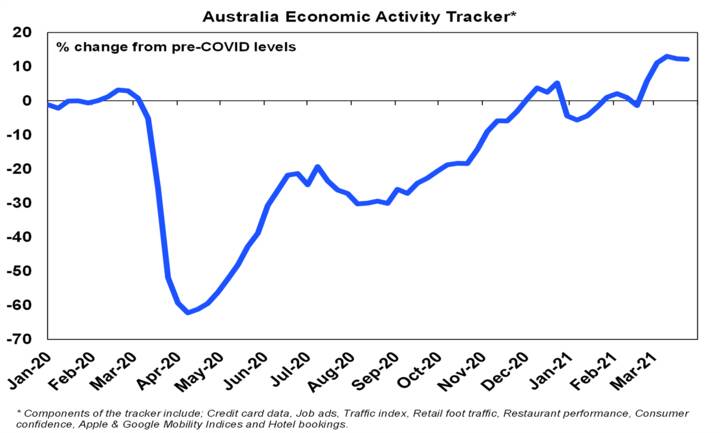

- Our Australian Economic Activity Tracker of weekly economic data is now running well above year ago levels suggesting that GDP is now above pre-coronavirus levels.

- Employment has now recovered 99.8% of the jobs lost in the lockdown. While the end of JobKeeper may see a slight rise in unemployment this is likely to be modest given a sharp decline in those working zero or significantly reduced hours and job ads running well above year ago levels.

The rapid recovery reflects a combination of reopening, government support measures and significant pent-up demand.

On top of this annual headline inflation is likely to rise towards 4% this quarter as last June quarter’s price falls drop out of annual calculations, higher oil and commodity prices along with goods supply bottlenecks impact and flood driven rises in fresh fruit and vegetable prices in Australia impact.

So why is the RBA still so cautious and dovish?

There are several reasons why the RBA remains very dovish.

- First, the recovery remains dependent on getting and keeping coronavirus under control.

- Second, some parts of the economy are lagging with RBA Governor recently singling out business investment.

- Finally, and more fundamentally, the economy is still a long way from operating at full capacity.

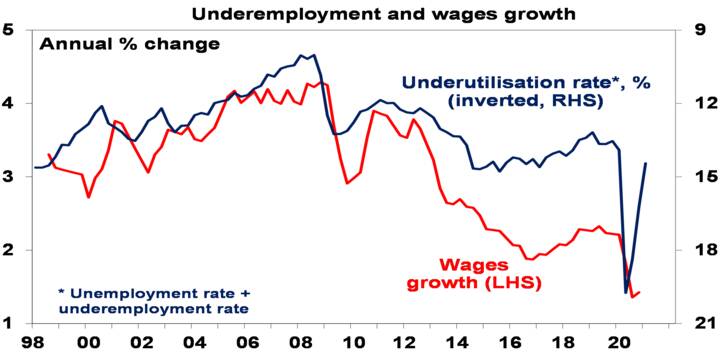

The last point is key. In the absence of a sharp rise in wages growth locking in higher inflationary expectations the pickup in annual headline inflation this year will likely be temporary as the volatility around childcare and petrol prices drops out, goods supply picks up and consumer demand swings back to services. Assuming productivity growth of around 1% a year, annual wages growth really needs to be 3.5% or more to be consistent with inflation sustainably in the 2 to 3% target range. But while labour underutilisation (ie, unemployment and underemployment) has fallen sharply from last year’s highs to 14.4% its only back to the high end of the range it’s been in since 2014 which saw wages growth stuck around 2% a year and was a key reason behind inflation running below target. To get wages growth above 3.5% year on year from 1.4% currently probably requires labour underutilisation to fall to around 10% or below – which in turn likely requires unemployment to fall below 4% with underemployment running around 6%.

At present with unemployment at 5.8% and underemployment at 8.5% we still have a long way to go. So, it makes sense for the RBA to remain dovish and cautious. The RBA has now been undershooting its 2-3 percent inflation objective since around 2015, and wages growth has been running below levels necessary to meet the target since 2012. Since mid-last decade the RBA’s inflation forecasts have proved chronically too optimistic (as did most economists’) and so too did its periodic assertions that the next move in rates is likely to be up.

The danger for the RBA is that a premature tightening in monetary policy before full employment and 3.5% wages growth are met will keep inflation averaging below the 2-3% target. And the longer this persists the more it will become entrenched and harder it will get to meet the target.

So, having learned its lesson from the post GFC experience the RBA (like the Fed) has changed its approach to focussing on actual inflation being sustained within the target rather than forecast inflation and to a focus on the labour market conditions necessary to achieve this. The shift to focussing on actual as opposed to forecast inflation means that it will necessarily be slower to raise rates which in turn will provide a window for inflation expectations and hence wages growth to move higher to help ensure inflation averages in the target range.

But why not just lower the inflation target?

Put simply, lowering the target would be nuts: if the target is moved whenever it’s breached, it won’t be taken seriously; statistical measures of inflation tend to overstate actual inflation and targeting too low inflation could mean we are knocked into deflation; deflation is not good if it means falling wages, high unemployment, falling asset prices and rising real debt burdens; and, it’s not just about below target inflation but also about achieving full employment and decent wages growth. A failure to achieve this is not socially desirable as its unfair, contributes to a sense of dissatisfaction & can give rise to social tensions.

What are the risks with the RBA’s approach?

There are two key risks: financial instability associated with asset price bubbles & excessive debt on the back of a lengthy period of ultra-low interest rates; and a breakout in excessive inflation. Dealing with these in turn:

- The main concern around financial instability relates to the property market. The experience since 2017 indicates that this can be dealt with partly by tightening lending standards when rates can’t be raised. The RBA and APRA are keeping a close eye on it but don’t seem too worried about lending standards just yet. History tells us though that booming prices like we are now seeing invariably leads to lax lending standards, so it makes sense to start tapping the lending standards brake sooner rather than later.

- The RBA’s now ultra-aggressive approach to boosting inflation risks higher than desired inflation on a medium-term view say in the next 3-5 years.

What is the outlook for RBA policy?

Given the speed of the recovery we think there is a good chance that the RBA’s objectives for a rate hike will be achieved before the “2024 at the earliest” that it refers to and so are allowing for a first rate hike in late 2023. But that’s still a long way off. Key to watch will be unemployment heading towards 4% and wages growth heading above 3%.

However, if the economy continues to recover as expected (or faster) it will be appropriate to start winding down/ending some of its other monetary policy support measures this year.

- The provision of cheap funding to banks under the Term Funding Facility is scheduled to end in June and this is appropriate given funding markets are functioning well.

- It would make sense to leave the 0.1% bond yield target focussed on the April 2024 bond rather than moving out to the November 2024 bond to allow the period of the 0.1% target to “time decay” as the bond matures.

- Tapering longer dated bond buying (from around $5bn a week now to say $2.5bn a week) from September providing the $A is not too far above that justified by commodity prices and other central banks are also slowing QE is also likely.

Implications for investors?

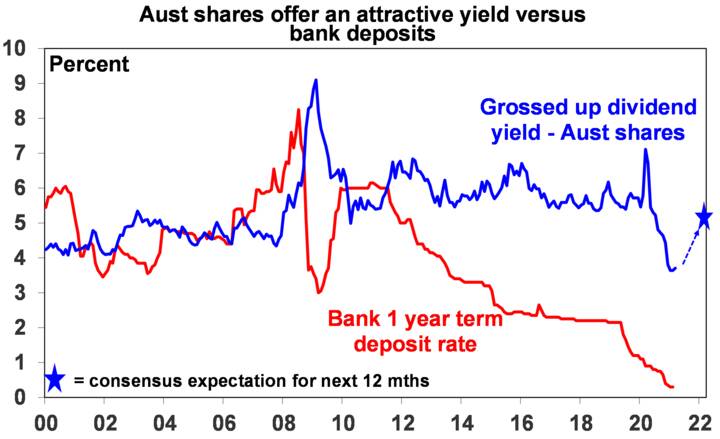

There are a number of implications for investors from the RBA’s slower reaction function. First, ultra-low interest rates will likely be with us for several more years, keeping bank deposit rates unattractive. Second, the low interest rate environment means the chase for yield is likely to continue to some degree supporting assets offering relatively high sustainable yields. This is likely to include Australian shares where dividends are rapidly recovering and likely to result in a grossed-up dividend yield of 5.2% over the next 12 months.

Third, variable rates will remain ultra-low supporting the property market for a long while yet but bear in mind that four year fixed mortgage rates are now edging up with the rise in long term bond yields and this along with continuing low population growth will start to take some of the heat out of the property market through 2021-22.