by Michael S. Canter and Monika Carlson

The market for single-family homes in the US has been solid since the global financial crisis ended, but the pandemic accelerated recent trends. As constrained housing supply met amplified demand, home prices heated up. In past hot markets, rising interest rates reduced affordability, which slowed or even reversed home price trends. Could this time be different?

Housing Supply Is Anemic…

Even before the pandemic, the supply of single-family homes had never recovered from the global financial crisis. Construction workers displaced when the housing market froze in 2008 found other jobs. Builders burned by the housing collapse refocused their attention on the steadier multifamily sector. Over the last four years, immigration policy changes helped keep the construction labor market tight, increasing costs. Post-crisis budget-cutting municipal layoffs also contributed to the bottleneck, with fewer building-permit clerks and building inspectors.

The pandemic exacerbated this housing shortage. Home-buying intentions fell off a cliff early in the pandemic, though that rapidly reversed course. Then the pre-pandemic supply problem worsened. Potential sellers postponed listing their homes, causing a decline in existing homes available for purchase. New home construction couldn’t make up the supply shortage (Display).

The forbearance and rental assistance programs enacted during the pandemic also reduced the available housing supply by preventing foreclosures, keeping those homes off the market. And this effect should last: Because many homeowners either refinanced or brought their mortgages current under those programs, we don’t expect a glut of homes to hit the market when the programs end.

…While Housing Demand Is Robust

In past housing booms, harmful lending practices and excess supply encouraged demand. In contrast, there are three good reasons for strong demand in today’s market.

First, a generational phenomenon is raising demand for single-family homes. Millennials—an even larger cohort than baby boomers—have recently moved into their home-buying years, driving demand.

Then came the pandemic. For many, urban living lost its charm. Others found they needed more room. For some, low rates meant they could buy sooner than anticipated.

Absent anything else, this generational shift would create a slow and steady increase in demand, but with housing stock restricted by the pandemic, the resulting upward pressure on the housing market has been profound.

Second, after months of lockdowns and work-from-home requirements, many Americans became interested in changing their surroundings, moving away from dense populations and out of multifamily housing. A survey conducted by UBS Evidence Lab found that 45% of respondents had an increased interest in homeownership since the pandemic began.

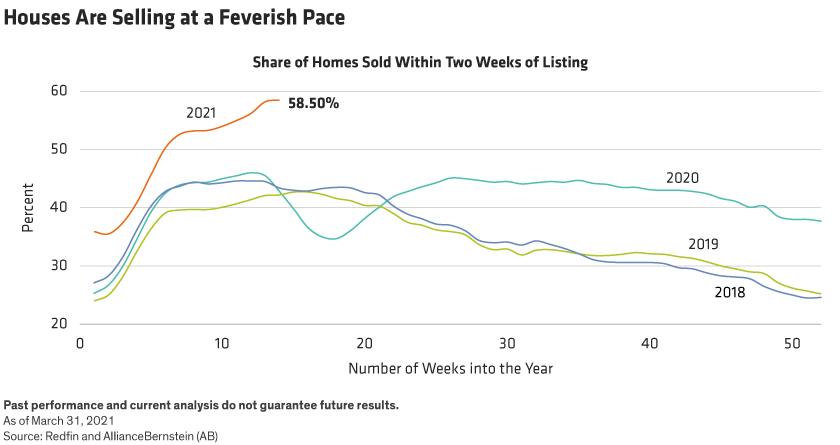

In less densely populated areas, single-family homes with more room, yards and privacy are selling with record speed—and on average nearly 60% of homes are selling within two weeks of listing (Display).

As a result of the quick turnover, while home prices are up only 2.4% for the most densely populated cities, prices increased more than 10% year-over-year in less densely populated areas.

Finally, institutional buyers—a new source of single-family housing demand—have bid up prices. Several publicly traded companies and hedge funds use technology to buy and manage thousands of single-family homes across the country as rentals. We expect these investors to be a permanent part of the demand for US housing.

Housing Price Slump Coming? Not So Fast.

In theory, rising home prices combined with rising interest rates reduce affordability, which could lead to a housing market slump. Here’s why we don’t think that’s likely to happen this time.

Low rates have helped keep housing affordable for some time. Even though the benchmark 10-year US Treasury rose from about 0.90% to 1.74% in the first quarter, mortgage rates remain near historic lows. Central bank officials worldwide are signaling that rates will stay low for a very long time. Even if interest rates rise by 50 or 100 basis points, we expect the affordability index to remain in the range we’ve seen since 2009 (Display).

Consumers are in a better position to afford homes, too. Household savings rates shot up during the pandemic, and the incomes for potential homebuyers increased faster than the median income over the past several years. As a result, even in the face of significantly tighter mortgage underwriting standards, credit-worthy consumers can join the home-buying frenzy.

However, the affordability picture isn’t entirely bright, because prices continue to rise quickly. Eventually, the job and economic growth will need to catch up with the increase in housing prices, or these gains may become difficult to sustain.

Keys to Housing’s Future

We expect solid demand for housing to continue post-pandemic. Over the next year, economics and demographics will drive single-family home price appreciation at a less frantic pace than the current 11.2% year-over-year increase. In the near-term, prices should increase between 3% and 6%, in our view.

Over time, pandemic-induced housing pressures will cool down, but other demand drivers and relative affordability are likely to keep the market warm. Pent-up demand, greater work-from-home flexibility, disciplined homebuilders, relatively low mortgage rates, institutional buyers and home-hungry millennials should support prices for the foreseeable future. Additionally, while mortgage underwriting standards tightened significantly during the pandemic, some easing to more normal levels could also help support demand.

Investors can take advantage of these expectations for continued housing market strength through investments such as credit risk–transfer securities. While the housing market can run hot and cold, we expect the confluence of these unusual forces to keep it in balance.

Michael Canter is Director—Securitized Assets and US Multi Sector at AB, and Monika Carlson is Senior Investment Strategist—Fixed Income at AB.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams and are subject to revision over time.