There are few investors currently prepared to take a contrary view on inflation. Most are expecting it to rise but view it as transitory – a shorter-term consequence of COVID-19 that’s already broadly priced into markets.

But what if near-term inflation surprises on the upside? What if higher inflation is here to stay for the longer term? We’d argue many portfolios are poorly positioned for these outcomes, yet there are some major socio-macroeconomic shifts that could see inflation skewed higher for longer.

At Antipodes, we’re expecting more volatility in inflation relative to what we’ve seen in recent history. Our inflation modelling suggests US headline inflation could hit north of 5% by the end of the year, versus an average closer to 2% over the last two decades, while core inflation (excludes food and energy) could begin to rise in a sustained manner from next year.

There are a number of key drivers supporting the notion of higher inflation, for longer.

Never-before-seen fiscal stimulus

40% of all money ever created occurred in the last year. This is a dramatic figure that puts into perspective just how much stimulus and money creation we’ve seen in response to the pandemic.

Today, quantitative easing (QE) is being used to fund aggressive fiscal stimulus – a change from what we’ve seen in recent history.

Fiscal stimulus finds its way more directly into the real economy, stimulating activity not just asset prices. Because of this, there can be much more volatility in inflation relative to what we have seen in previous periods of QE.

Consider US households. Thanks to stimulus and underspending in 2020, personal savings rates in the US are nearly 30% of disposable income. This is almost 5x the long-term average of 6%. That’s a lot of firepower that can be deployed as the US economy fully reopens.

The extent to which this excess savings and pent-up demand is inflationary will depend on how much is spent versus saved. But to labour the point, US consumers have accumulated $3t in above trend excess savings – this is equivalent to almost 20% of total annual personal consumption in the US, with more stimulus in the pipeline for middle-income Americans. Even if just one-third of this $3t is spent, it equates to 5% of GDP. This is pretty powerful.

The point is consumption can overshoot in the near term. This means inflation can overshoot too.

Now, you may ask – what about Japan which experimented with QE well before the rest of the world and has failed to generate any meaningful inflation?

Every time Japanese policymakers caught a whiff of inflation, the brakes were tapped. Money supply growth rarely exceeded 5% in the last 35 years. This is different to the actions of policymakers today, particularly in the US and Eurozone, where it’s pedal to the metal. Today, global money supply growth is 35% higher yoy.

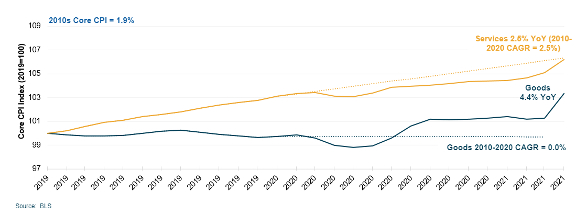

Service sector inflation vs goods inflation

Over the last ten years goods inflation has run flat in the US; a consequence of China entering the global trading system. Since the pandemic, however, the goods sector has been inflating, now running well above trend at 4.4% YoY. This is thanks to disruptions in supply chains, and rising raw material, energy, transport and labour costs.

Service sector inflation, on the other hand, has just reached ten-year trend levels. It had been running below trend as travel, eating out, entertainment was a big source of underspending during the lockdown.

So what could the longer-term picture look like? Spending on services is quickly normalising as economies fully reopen. Undoubtedly, there are pandemic related pressures in the goods sector that will fall away, but some of this inflation could prove sticky over the longer term due to structural forces.

If goods inflation remains above trend at, for example, 1.7% YoY, US core inflation could settle around 2.2%, which is 0.3% above trend.

While this doesn’t sound like a lot, it’s meaningful in the context of the consensus view.

Populism and China: Structural shifts in longer-term inflation

The rise in populism

Policymakers globally are being forced to address the rise in populism and wealth inequality. There is evidence of this unfolding almost everywhere we look.

Taking the US as an example, both sides of politics appear committed to addressing wealth disparity. This is bedded in part by self-interest; apart from avoiding social unrest, these citizens are the bulk of the voter base.

Today’s unemployment benefits in the US are around 30% higher than the minimum wage, thanks to generous transfer payments from both the Trump and Biden administrations. So those that would normally earn the minimum wage are receiving a 30% pay rise to not work.

These unemployment benefits will last until at least September, and in the meantime, US companies big and small, across a variety of industries are indicating that an inability to hire workers is emerging as a key constraint.

Just a few weeks ago McDonald’s announced it is lifting its hourly wage by 10% in a bid to attract more workers. McDonald’s isn’t alone. There have been similar announcements from Walmart, CostCo, Bank of America. Even Amazon’s committed to lifting wages for more than 500,000 employees.

Wage hikes by some of the largest employers in America is a change worth paying attention to. Generous unemployment benefits may permanently impact the minimum wage and add an additional pulse to longer-term inflation.

Populism along with geopolitical tensions is also forcing governments to bring supply chains home. COVID brought to the fore risks relying on a very lean, just-in-time inventory system that’s dependent on manufacturing capacity in other parts of the world.

At the same time some major shifts are underway in China – the engine room of global manufacturing over the past few decades.

Changing China

Over the last 30 years, China’s industrial sector developed into the largest scale, lowest cost production centre the world has seen – which has made China a major global deflationary force.

The Central Government, however, is now prioritising decarbonisation and weaning weak and inefficient state-owned enterprises off government aid. Inefficient capacity is closing in addition to capacity restrictions in industries with high carbon intensity, like steel, aluminium and chemicals. We could see structurally higher raw materials prices going forward.

China’s integration into the world economy also saw a one-time doubling of the global supply of labour, and the cost of this labour was significantly cheaper than the rest of the world. In 1990 labour in China was 60% cheaper than in the US.

But this labour arbitrage has been closing – by 2018 the gap had fallen to 20% cheaper. What investors need to focus on is the transition in China’s demographics that’s occurring over the next decade or so.

Today, around 50% of Chinese households have an average household income of US$7,200. By 2030 we believe this will shrink to less than 20% of total households. Incomes are rising. The pool of low-cost labour that the rest of the world has tapped into is significantly shrinking.

The question is can other emerging nations fill the void? China had a unified national strategy when it came to industrialisation, as well as access to cheap, and seeming limitless, capital. This allowed China to achieve scale that has so far been unmatched. On the margin, some manufacturing will bleed into other low-cost regions but it will be near impossible to replicate the China model.

What does a higher inflation outlook for longer mean for equities?

To answer this we need to consider where the market is today and how we got here.

In recent years investors have been prepared to pay more for stocks with bond-like characteristics than they have in the past, similar to levels we last saw during the dot.com bubble.

These are high growth business where investors expect meaningful cash flows in the future as well as defensive businesses with stable returns. This isn’t just a preference for tech stocks – we can see a preference for bond-like equities in every sector, globally.

The low-yield environment over the past decade has driven this preference.

Bond yields are an outcome of future expectations of inflation and real economic growth. As inflation rises so too will bond yields. This will ultimately force the market to reassess what it’s willing to pay for these bond-like equities, given they are on very high multiples.

This has important implications for diversification. Stocks and bonds usually move in the opposite direction, but as inflation rises bonds and equities will sell-off together. This has the potential to be extreme given bond-like equities account for over half of today’s global market cap.

That doesn’t mean we can’t diversify using bonds and equities – but it does mean we need to be selective about the stocks we own. Higher yields are typically a tailwind for low multiple, or value, stocks.

When it comes to equities, we’re focusing on resilient businesses that are market leaders; companies that can pass on higher costs to customers.

Examples of dominant brands in our portfolio include Lowe’s, the second-largest US home improvement chain, Yum China, the largest quick-service restaurant franchise in China, and our auto exposures like VW and Toyota which are already passing on higher input costs.

Weaker businesses won’t be in the same position to protect profitability as costs rise.

We also have exposure to companies that will be the source of inflation, like global aluminium producer Norsk Hydro. Norsk will be a direct beneficiary of rationalisation of capacity in China and may be able to charge a premium for its ‘green’ aluminium made from hydropower versus the traditional coal-based producers.

Remember, bond yields will respond to inflation. We need to be careful what we pay for growth, as growth traps will be revealed in higher inflation and higher yield environment.

It’s why we think searching for pragmatic value opportunities is so important.

The Antipodes Global Fund invests in companies listed on global share markets and aims to achieve absolute returns in excess of the Benchmark over the investment cycle (typically 3-5 years).