Introduction

A year ago, the big worry was depression and deflation, but the big worry now appears to have shifted to inflation. Just as share markets surprised with their rebound, and economic conditions did the same, now it seems inflation will do likewise. But what’s driving higher inflation? Is the inflation surge permanent or transient? What’s the longer-term inflation outlook? What will it mean for investment markets? And what are the best hedges against higher inflation?

Inflation on the rise

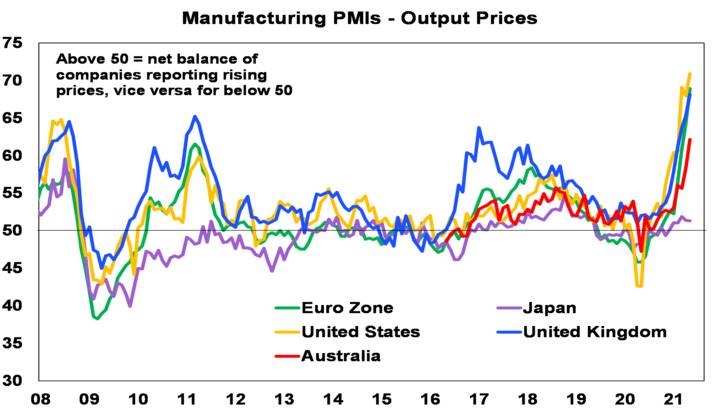

An uplift in inflationary pressures has been increasingly evident over the last six months or so. First, in higher commodity prices, then in various business surveys indicating goods supply bottlenecks and rising input & output prices (see next chart) along with higher producer price inflation in some countries.

Source: Markit, AMP Capital

And now in accelerating consumer prices. This is most evident in the US with April CPI inflation surging to 4.2% year on year, and now in signs of higher wages growth there.

So far, it’s less evident in other countries’ inflation measures – which have moved up but only to 1.6% yoy in Eurozone and to –0.4% yoy in Japan in April and have only increased to 1.1% yoy in Australia for the March quarter. For Europe & Japan this may be because their recovery has lagged, but it’s likely they will see a further rise too given global pressures. In Australia CPI inflation is likely to rise to around 3.7% this quarter.

What’s driving the rebound in inflation?

The key drivers of the rebound in inflation are a combination of:

- base effects – as last year’s deflation drops out of annual calculations, eg, US consumer prices fell -1.1% over the three months to May 2020 and Australian consumer prices fell -1.9% in the June quarter last year;

- higher commodity prices as pandemic related stimulus focussed on boosting investment, particularly in China;

- goods supply bottlenecks due to cuts to production in the pandemic and then consumers switching spending to goods from services leading to low inventories;

- reopening leading to a rebound in some prices; and

- higher wages growth as extended unemployment benefits discourage workforce participation.

In line with this, it’s notable that the surge in inflation in the US in April was not broad based. Just four groups with a weight of about 12% in the core (ex food & energy) CPI accounted for around 70% of the 0.9% monthly rise in core inflation – including used car and truck prices, airfares and hotels. The median CPI which gives a better guide to underlying inflation rose just 0.2% in April or 2.1% yoy and indicates the rise in CPI inflation was not broad based. In the months ahead, annual inflation in the US and elsewhere will likely push even higher as base effects have further to go, bottlenecks persist and reopening continues.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

Is the inflation spike permanent or transient?

No one knows for sure, but while the risks have increased, we are of the view that the inflation spike will prove temporary as:

- the base effects will drop out and then reverse, eg, a +1.4% rise in US consumer prices over the 3 months to August 2020 and a +1.6% rise in the CPI in Australia in the September quarter 2020 will drop out of annual calculations;

- industrial production will pick up in response to the surge in prices, boosting supply and depressing prices;

- consumer spending will rotate back to services from goods;

- some sectors like traditional retailing, corporate travel and CBD services will see a longer lasting hit to jobs; and

- in the US school re-openings and the ending of enhanced unemployment benefits in September will push more workers back into the workforce.

So, inflation is likely to fall back again from later this year. There are some very tentative early signs of this with some commodity prices rolling over (eg, lumber, corn and iron ore) with China’s removal of stimulus and crackdown on speculation impacting, semiconductor chip prices trending down and business surveys showing a decline in the ratio of new orders to inventories. There is a long way to go before this is confirmed though.

Source: Markit, AMP Capital

How will central banks react?

For the last few decades central banks – mindful of avoiding a return to the high inflation 1970s – acted aggressively to head off excessive inflation by tightening monetary policy whenever growth picked up in advance of higher inflation. This kept inflation low and most importantly kept inflation expectations low – which prevented inflationary shocks, eg, higher oil prices, feeding through to a permanent rise in inflation. But in the post-GFC period, along with aggressive deflationary forces, we saw inflation start to run well below target. So last year the Fed and the RBA committed not to raise rates until actual inflation (opposed to forecast inflation) is sustained at target (or above target for the Fed). This is aimed at pushing demand & inflation expectations up to be more consistent with inflation targets.

So, the Fed and other major central banks are likely to avoid rushing into rate hikes. Major central banks fear that jumping at what should be a transitory spike in inflation will risk slowing recovery prematurely and repeat the mistakes of recent times. They would rather look through any spike in inflation and allow the recovery to continue until full employment is reached, generating higher wages growth which may be a few years away – Australia needs 3% plus wages growth to be consistent with inflation at target whereas it’s now just 1.5%.

The Fed and RBA will likely follow the Bank of Canada & Bank of England in slowing bond buying – but this is not monetary tightening and if they remain dovish on interest rates as expected it will mean any near-term inflation-driven bond market panic & hit to share markets will likely be short lived. Key to watch will be inflation expectations and wages growth.

What’s the longer-term outlook for inflation?

Viewed in a longer-term context though, we’re likely now going through the bottoming of the long-term decline in inflation that has been in place since the early 1980s:

- After years of undershooting on inflation, central banks and governments are now taking a more aggressive approach to pushing inflation up to their targets. The shift from focussing on forecast to actual inflation means central banks will be slower to raise rates allowing inflation to rise further, and massive quantitative easing is now being combined with fiscal stimulus which provides an avenue for easy money to boost spending (unlike last decade when fiscal austerity offset easy money). This likely constitutes a “regime shift” in the approach to boasting inflation – much like the aggressive approach to keeping inflation down led by the Fed from the early 1980s was a “regime shift”.

- We’re seeing a trend to bigger governments and that can ultimately be associated with lower productivity growth.

- Globalisation appears in decline meaning less competition.

- The ratio of workers to consumers is declining in many countries which may drive higher wages growth and lower productivity growth.

The bottom line is that many of the factors that drove the declining trend in inflation since the early 1980s are now fading. In this context the spike in inflation now occurring is likely part of a longer-term bottoming process. However, it’s not all one way (technological innovation is still bearing down on prices, and the pandemic may work to drive more productivity) and the 1960s showed us that the bottoming of inflation will take many years to play out. The question is whether it results in inflation averaging around target or something higher. Our base case is the former.

What will it mean for investment markets?

In the next few months, a further rise in inflation will likely push bond yields higher which may further threaten shares (particularly tech stocks which are vulnerable to higher interest rates). So, shares are at risk of a further near-term correction.

However, the likely fall back in inflation from later this year (combined with central banks remaining dovish) will mean that any near-term bond market panic and hit to share markets is likely to be short lived. Cyclical bull markets usually don’t end until excesses build, central banks tighten aggressively, and this drives a collapse in earnings. But this still looks a long way off. As a result, we remain of the view that share markets will provide solid gains over the next 12 months.

Longer term, the bottoming in inflation & long-term bond yields after a 40-year downtrend will mean that a tail wind that has helped propel growth assets higher – as lower bond yields and less inflation uncertainty drove progressively lower investment yields and higher PEs which in turn meant higher returns than would be implied by increases in earnings and rents alone – will start to fade, resulting in returns more constrained to underlying yields and earnings growth. Inflation around target is the best scenario as it would still mean low inflation – but less risk of deflation and likely higher wages growth (which is positive in terms of social stability, rising living standards and equality) – and investment returns would still be ok.

Of course, if inflation gets out of control again and rises beyond inflation targets (which is not our base case given central banks are still focussed on inflation targets and technological innovation will impose some brake on inflation) the valuation boost from low inflation will be reversed, resulting in poor returns from growth assets.

What are the best hedges against higher inflation?

For those worried about a return to much higher inflation driving much higher bond yields and weighing on sectors like high PE tech stocks, the best protection would be inflation-linked bonds, real assets (like commodities) and parts of the share market that will see stronger earnings growth.