Introduction

The drumbeat of central banks heading towards the exits from ultra-easy monetary policy is getting louder. It started with the Bank of Canada, then the Bank of England followed by the RBNZ and the Bank of Korea. Russia and Brazil have raised rates. The US Federal Reserve is starting to “talk about talking about tapering” (or slowing) its bond buying, and Fed officials are signalling the start of rate hikes in 2023 via the so-called “dot plot” of the median Fed official’s interest rate expectations. While Fed Chair Powell played down the importance of the dots, it was still too big a move to ignore. Our view is that formal taper talk is likely to start at next month’s Fed meeting with actual tapering likely to start late this year or early next and that 2023 for the first Fed hike is a reasonable expectation.

In Australia, the RBA is also slowly heading towards the exit of easy money with: 0.1% funding for banks ending this month; the bond targeted for its 0.1% bond yield target up for review in July and likely to see the target slip below 3 years; its bond buying program also up for review in July and also likely to be reduced or reviewed more frequently; and a speech by Governor Lowe dropping a reference to the conditions for a rate hike as being “unlikely to be met until 2024 at the earliest.” For several months now we have been anticipating that the first RBA rate hike would come in 2023, and after the strong jobs data for May this seems to be becoming consensus. In fact, it’s possible (covid permitting) that the conditions for higher rates (wages growth of 3% or more and inflation sustainably in the 2-3% target) may fall into place by late next year enabling a rate hike at the same time, although our base case remains 2023.

The hawkish shift by central banks – notably since the Fed last week – has caused some wobbles in investment markets. Some are fearing the Fed and other central banks may not be as committed to sustainably achieving their 2% or so inflation targets as previously thought and that the hawkish Fed tilt will threaten the recovery. So, should investors be concerned?

Five reasons not to be too fussed

Shares are vulnerable to a correction – they have run very hard and we are now in a seasonally weak period of the year – so the rough patch could have further to go. However, we would see this as just normal gyrations for this stage in the cycle. Here are five reasons not to be too concerned by central banks.

First, central banks are reflecting the reality of global economic recovery – this is being reinforced by the deployment of vaccines but with monetary stimulus having done its job, the need for emergency monetary settings is starting to recede. The recent shift in tone from central banks is most unlikely to signal that they are backing away from their commitments to getting inflation sustainably back to target – rather it reflects the reality that as recovery has been stronger than expected they will likely meet their objectives earlier than previously expected. Consistent with this Fed Chair Powell’s comments this week have been calming.

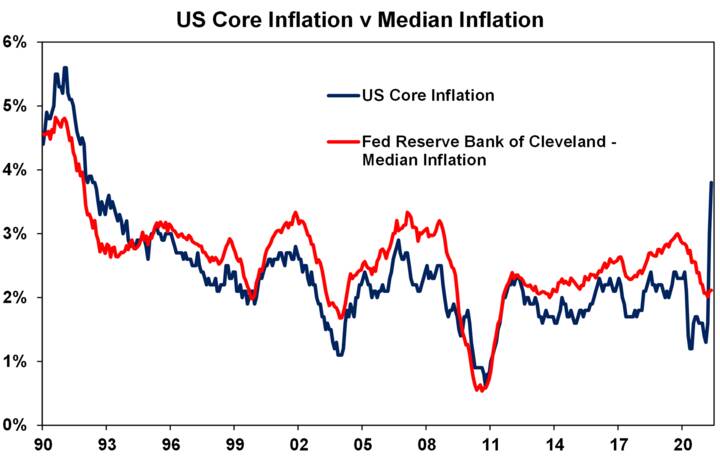

Second, monetary policy remains ultra-easy and is a long way from being tightened – tapering of bond purchases is not monetary tightening, it’s just slower easing. While some emerging country central banks have raised rates, rate hikes in the US and Australia are still 18 months to 2 years away and the ECB and Bank of Japan are further behind. While much concern has been expressed about the spike US inflation and in producer prices globally, the evidence suggests its transitory: the spike in US inflation is narrowly based on components impacted by the pandemic which won’t be sustained as things return to “normal”; reflecting this median inflation remains soft (see the next chart); various commodity prices have rolled over – with, eg, US timber prices down nearly 50%; and US wages pressure will subside as enhanced unemployment benefits end and schools return sending workers back into the jobs market and it will be similar in Australia when backpackers return.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

And of course, risks remain around the more contagious Delta variant of coronavirus even in countries where a big portion of the population has had a first vaccine dose but where it’s still not enough for herd immunity as the current UK experience highlights. This will keep central banks a bit cautious in terms of removing stimulus, at least until herd immunity is reached via vaccination programs. The RBA in particular is likely to be more cautious than the Fed given the threat posed by Delta variant outbreaks in Australia, with the lower level of vaccination here and given that the inflation spike is likely to be less in Australia.

Third, through the actual period of the last US taper from December 2013 to September/October 2014 US shares rose – this is likely because tapering is a slowing in easing not actual tightening and rates were still low. There is no reason to expect a different outcome through the next taper, particularly given that the start of tapering is being well flagged.

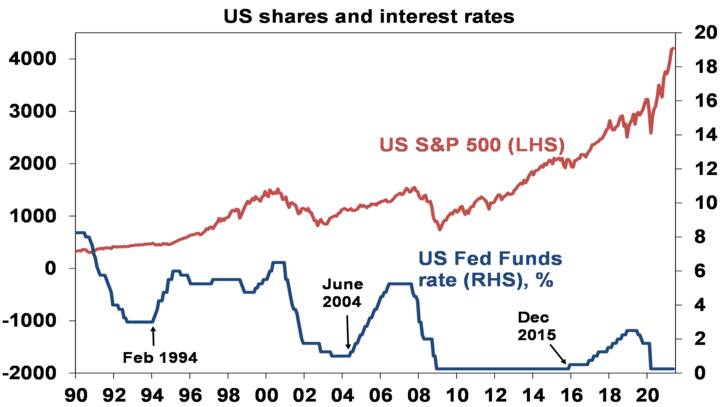

Fourth, even if the first rate hikes from the Fed and RBA are sooner than we anticipate the experience of the last 30 years suggests an initial dip in share markets around the first rake hike but then the bull market resumes– and continues until rates become onerously tight which weighs on economic activity and hence profits. This can be seen in the next chart for US rates and shares. Shares had wobbles when interest rates first started to move up in February 1994 (US shares had a 9% correction), in June 2004 (US shares had a 8% correction) and in December 2015 (US shares had a 13% correction) but thereafter they resumed their rising trend and a bear market did not set in till 2000, 2007 and 2020 after multiple hikes. Recession did not come for seven years after the February 1994 first hike, for three and a half years after the June 2004 first hike and for four years after the December 2015 first hike (and that was due to the pandemic). This is because the first rate hike only takes monetary policy from very easy to a bit less easy, and it’s only when monetary policy becomes tight after numerous rate hikes that the economy gets hit. This is all a long way off as even the first hike is a while away.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

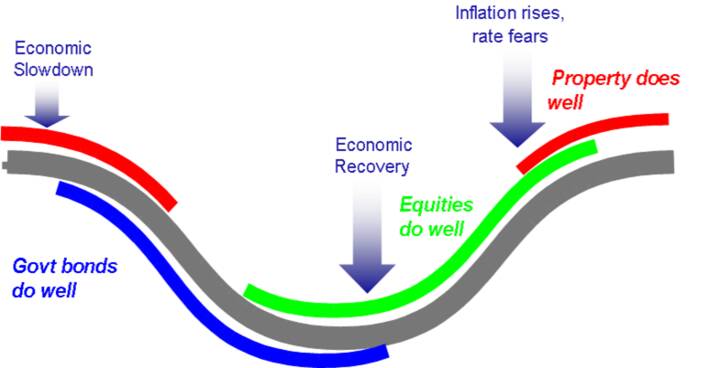

Finally, this is all consistent with where we are in the investment cycle – a stylised version of which is shown in the next chart. A typical cyclical bull market in shares – the green area in the chart – has three phases:

- Phase 1 normally starts when economic conditions are still weak and confidence is poor, but smart investors start to see value in shares helped by ultra-easy monetary conditions, low interest rates and low bond yields.

- Phase 2 is driven by strengthening profits as economic growth turns up and investor scepticism gives way to optimism. While monetary policy may start to tighten, it is from very easy conditions & remains easy as underlying inflation remains low and so bond yields may be moving higher but not enough to derail the cyclical bull market.

- Phase 3 sees investors move from optimism to euphoria helped by strong economic and profit conditions, which pushes shares into clearly overvalued territory. Meanwhile, strong economic conditions drive inflation problems and force central banks to move into tight monetary policy, which pushes bond yields significantly higher. The combination of overvaluation, investors being fully loaded up on shares and tight monetary policy sets the scene for a new bear market.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

Right now, we are likely in Phase 2 of the investment cycle. Monetary support is likely starting to diminish (albeit only slowly), and we are now more dependent on earnings growth. This shifting of the gears from the Phase 1 valuation driven gains typically sees some slowing in average share market gains. But the trend remains up and we are likely still a fair way away from the unambiguous overheating and exhaustion evident at the end pf a cyclical bull market.

Implications for other asset classes

There are several implications for other asset classes from central banks gradually moving to exiting monetary stimulus:

- It may weaken one source of demand for Bitcoin and so-called “meme stocks” – as the opportunity cost of holding Bitcoin rises with higher bond yields and demand for it as a hedge against inflation may diminish.

- Interest rates are gradually shifting from a tailwind to a potential headwind for Australian residential property demand. But as with shares, rates are still low and so this may not become a significant issue for a while but is likely to drive a slowing in property price gains and RBA rate hikes in 2023 will likely trigger price falls. The key for homeowners is to make the most of the currently still low fixed mortgage rates to get their debt down ahead of rate hikes.

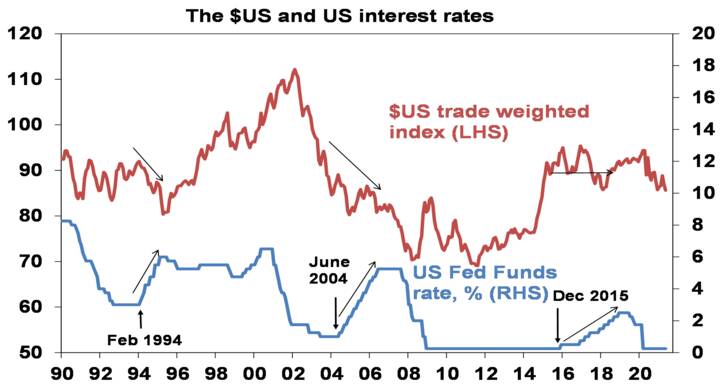

- While some may see a more bearish Fed as being positive for the US dollar, in reality it’s messy. For example, rate hikes in the 1994 and 2004 Fed tightening cycles saw the $US fall, which is consistent with the view that in times of economic recovery and rising rates, demand for safe haven currencies like the US dollar declines. So, while the $A could have some short-term wobbles, if the global recovery remains solid, the $A is likely to resume its rising trend.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital