by Andy Acker – Portfolio Manager and Agustin Mohedas – Research Analyst

It has been described as the Death Star of cancer mutations, and the quest for a drug to address it as the Holy Grail of cancer research. But finally, last month, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first therapy that targets KRAS, among the most frequently mutated oncogenes in human cancers. The mutation is often present in lung and colorectal cancers and is a signature of pancreatic cancer, which has among the lowest five-year survival rates of all cancers. In short, this medical breakthrough – pursued for roughly four decades – is a big deal.

Cancer research dominates

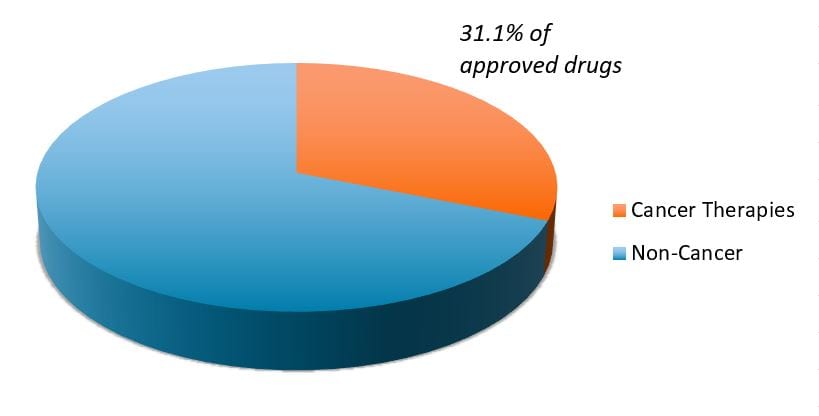

It also represents a broader trend occurring in biopharma. As more areas of medicine face generic competition, research efforts have pivoted toward oncology and other disease categories with high, unmet medical needs. At the same time, the cost of genetic sequencing has dropped from roughly US$1 billion in the early 2000s (when the first human genome was mapped) to a few hundred dollars today, leading to a boom in genetic disease research, including cancer. The net result has been a dramatic rise in new cancer therapies, which made up more than 30% of all novel drugs approved by the FDA in recent years (see chart).

FDA novel drug approvals (2015–2021)

We believe this pattern is likely to continue, with important implications for biopharma. Cancer treatments are evolving from the blunt approach of chemotherapy and radiation, which attempt to kill all rapidly dividing cells and distinguish poorly between healthy tissue and tumors. Instead, new therapies target specific driver mutations in cancer, such as KRAS, leading to more effective and better tolerated medicines that can prolong both survival and quality of life.

A more targeted approach

In healthy cells, KRAS serves as an on-off switch that regulates cell growth. When the gene mutates, KRAS can become stuck in the “on” position, allowing cells to multiply uncontrollably. The KRAS-targeting drug approved by the FDA, Lumakras (sotorasib), treats adult patients with non-small cell lung cancer, the most common type of lung cancer (roughly 200,000 people diagnosed each year in the U.S.1) For those in advanced stages of the disease, there typically is no cure. In clinical trials, more than a third of patients who received Lumakras saw their tumors shrink significantly. Of those patients, more than half saw the effect last six months or longer, representing a remarkable improvement in progression-free survival.

Lumakras targets one specific type of mutation, KRASG12C, which occurs in about 13% of non-small cell lung cancer patients, but other variations of the mutation exist. All told, KRAS mutations are present in approximately 25% of all tumors, creating a significant market opportunity.2 As such, a number of other companies are developing KRAS-targeted drugs, with at least one expected to go for FDA approval later this year.

Until recently, KRAS remained an elusive target because of the nature of the protein encoded by the gene: it lacked an obvious entry point for a drug. But after years of screening thousands of molecules, biochemists succeeded in finding not only an entry point but also a characteristic that occurs only with KRAS-mutated proteins. This has made it possible for scientists to develop a highly targeted treatment – one affecting only cancerous cells while sparing healthy ones.

Driving biopharma revenue growth

Such specificity is the future of cancer treatment and is being made possible by advances in technology. In fact, new technologies for small-molecule drug development, including structure-based drug design (which uses 3D visualization of proteins to guide drug development) and targeted protein degradation (which uses the cell’s natural waste disposal system to target cancer proteins for destruction), are opening up previously “undruggable” targets. Consequently, the number of cancer-focused compounds in late-stage clinical trials climbed 80% from 2010 to 2019, according to research presented at this year’s American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting.3

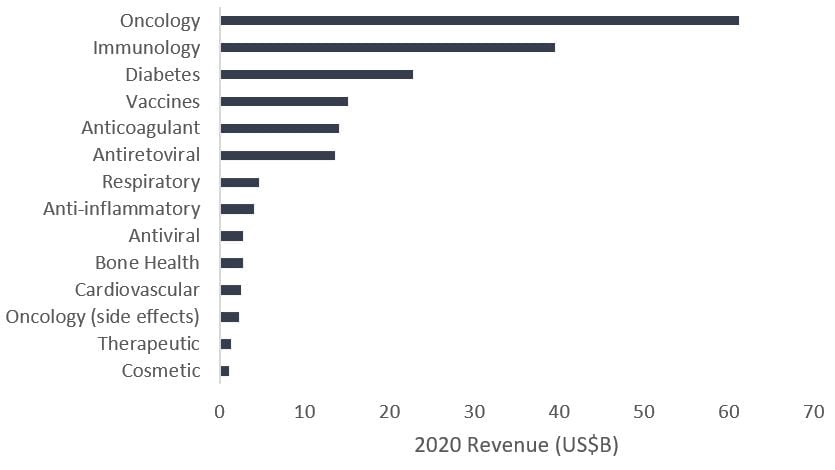

At the same time, the pharmaceutical industry is recognizing the growth potential, spending billions of dollars on research and development, partnering with developers and acquiring biotech firms pioneering much of the research. As a result, while revenues for some blockbuster drugs4 have started to decline as generic competition ramps up, biopharma oncology sales have exploded.

Total franchise sales of top medicines for select pharmaceutical and biotech companies

We expect the trend could continue over the next decade, particularly as big data and machine learning capabilities improve, new drug targets are discovered, and a growing middle class around the globe – much of which is aging – increasingly seeks new cancer treatments. In our view, large pharmaceutical and biotech companies that integrate targeted cancer approaches into a diversified pipeline of new medicines could bolster their growth, offsetting the negative impacts of patent expirations and potentially surprising investors.

ENDNOTES

1American Cancer Society. Data estimated for 2021, as of 12 January 2021.

2The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, as of 12 February 2021.

3“Temporal Trends in Oncology Drug Revenue Among the World’s Major Pharmaceutical Companies: A 2010-2019 Cohort Study,” Daniel E. Meyers, M.D., M.Sc., University of Calgary. 2021 Annual ASCO Meeting, 4 June 2021.

4A blockbuster drug is defined as having annual sales of U.S. $1 billion or more.