Introduction

News that I and many others were effectively in lockdown from Friday was depressing. It got even more depressing when the whole of Sydney and surrounds was put into a two-week lockdown on Saturday. And I am not in Victoria which has had it even worse over the last year, and I can only imagine how bad this must be for those looking forward to school holidays. Or far worse still for those with businesses dependent on people coming together. And now Perth & Darwin are in lockdowns too.

With Sydney and surrounds having around 6.6 million people and about 25% of Australian GDP we estimate a hit to national economic activity from the two-week Sydney lockdown of around $2 billion (or 0.1% of GDP). Perth’s four-day lockdown will cost another $200m and Queensland’s three-day lockdown another $300m. And this follows around a $1.5bn hit from Victoria’s two-week lockdown from late May.

With ongoing lockdowns, it seems like ground hog day. Some even think the lockdowns themselves are the problem – that Australia has become paranoid, going into lockdown & shutting borders at the whiff a new case, locking out the rest of the world and becoming a “lost kingdom of the South Pacific” – imposing a great cost on the economy all to control what some think poses no or little risk for most, or is just a bad dose of the flu.

Australia has made some mistakes. High on the list is: the slow rollout of vaccines; the management of the returned traveller quarantine system; the poor treatment of Australians overseas (particularly those recently in India); and we arguably have been too slow in relation to starting some lockdowns (in Victoria mid-last year and recently in NSW) risking longer lockdowns.

But gloomy as it all seems, Australia’s approach has led to relatively less deaths and a stronger economy. And being early in the vaccination process – both globally and in Australia – it’s still too early to simply relax controls. This note puts it into perspective and what it means for investors.

1. Healthy people = healthy economy

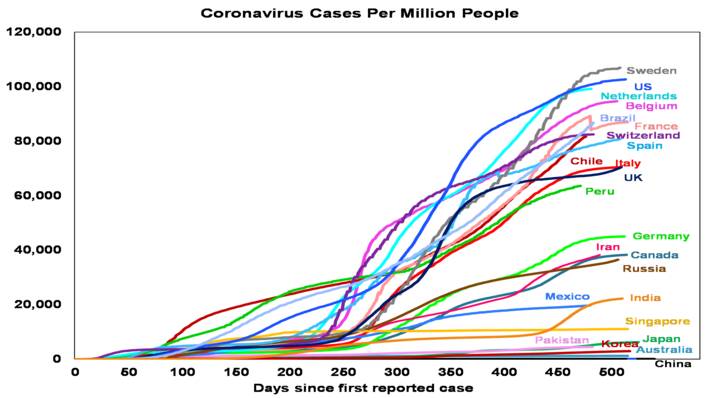

The first thing to note is that Australia has performed relatively well through the coronavirus pandemic. Early last year I also thought it may be a bad case of flu, but quickly changed my mind in March last year when it was clear that it was far worse and if not controlled, the hospital system would be overwhelmed leading to more deaths. The occurrence of “long covid”, potential long-term health effects even in the young and now more transmissible variants reinforce this. So, thanks to a sensible health response, rigorous application of restrictions and periodic snap lockdowns after the initial lockdown we have been able to keep cases and deaths per capita relatively low.

Source: ourworldindata, OECD, ABS, AMP Capital

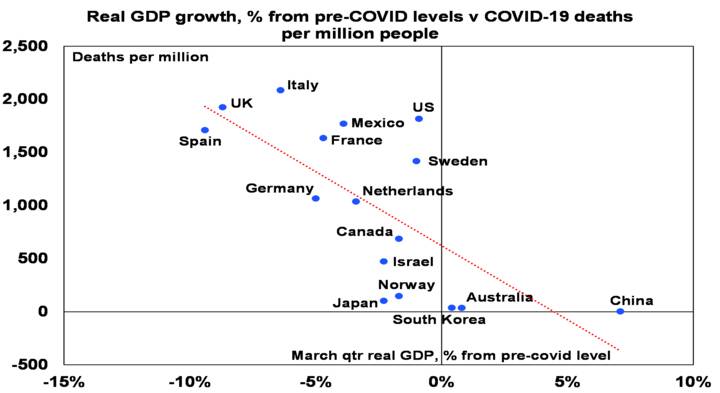

As evident in the next chart, better health outcomes in terms of deaths per capita (vertical axis) have been associated with better economic performance as measured by GDP (horizontal axis). Along with well targeted government support that protected incomes, jobs and businesses Australia is one of the few developed countries with GDP above pre pandemic levels.

Source: ourworldindata, OECD, ABS, AMP Capital

Better control of the virus has enabled much of Australia to go about life with relatively modest restrictions over much of the last year in contrast to many countries that have seen almost continuous lockdowns, with some only just coming out of them.

Even countries that adopted a laxer approach such as the US or a “let it rip” approach like Sweden saw a bigger hit to their economies than Australia did. If Australia had a laxer approach and as a result had the same per capita deaths as the US, it would have lost an extra 47,000 Australians on top of the 910 deaths so far. More deaths and a worse economy do not strike me as a compelling case to avoid lockdowns.

2. Snap lockdowns work

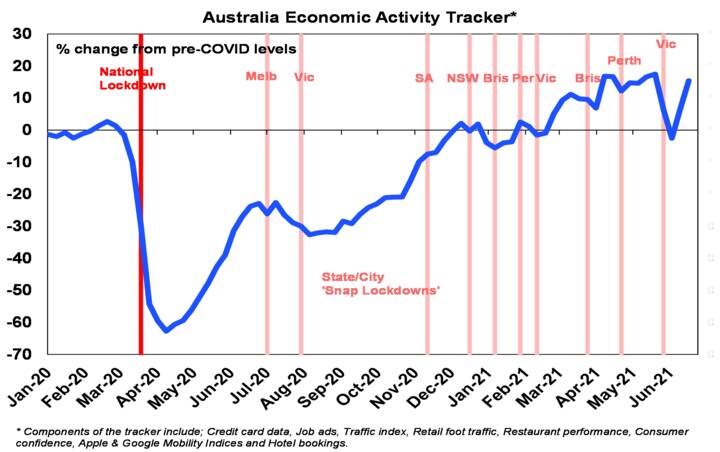

Australia has already had eight snap lockdowns since November last year and the evidence strongly suggests that if applied early when the flow of new cases is relatively low, they head off a bigger problem with coronavirus and hence a longer and more economically damaging lockdown (in the absence of course of most being vaccinated). “A stitch in time saves nine” as the old saying goes! Providing they are short, the economic impact is relatively “minor” (although still horrible) as spending and economic activity is delayed, which then bounces back once the lockdown ends. This is evident in our weekly Australian Economic Activity Tracker (see the next chart), which combines weekly data and shows a rising trend in economic activity through the snap lockdowns since last November, including after Victoria’s recent snap lockdown ended.

Source: AMP Capital

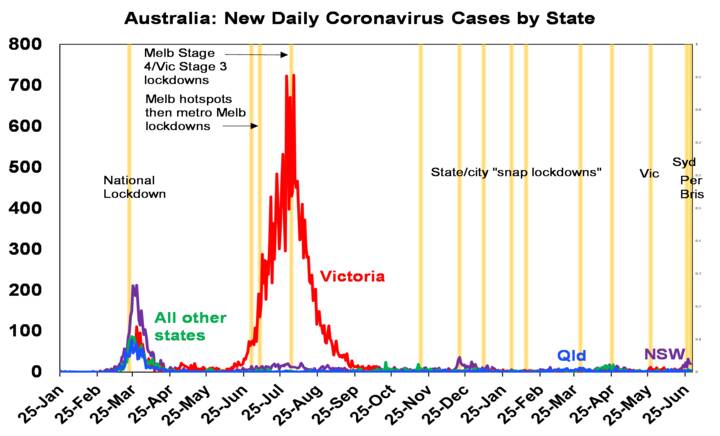

Ideally, the Sydney lockdown should have started a few days earlier when the flow of new cases was lower, but starting at around 20-30 a day was still relatively low compared to last July when the Melbourne hotspot lockdown started when new cases were already spiralling over 60 a day or the over 600 a day when the full Victorian lockdown started in August. This should provide some confidence this lockdown will work in controlling the spread of new cases and can be limited to two weeks or so. See the next chart which puts it into perspective.

Source: covid19data.com.au

If so, while we estimate a hit to economic activity from the Sydney lockdown of about $2 billion if it’s contained to two weeks, much of that will likely be recouped upon reopening. Of course, the risk is greater now that we are dealing with the more virulent Delta variant, but so too was Victoria in late May.

3. Border confusion

Everyone wants freedom to travel out of Australia and back in, and an open international border is key to having a dynamic economy long-term, but its short-term importance to the recovery is exaggerated. First, the economy has already rebounded beyond pre-coronavirus levels. Second, Australia normally loses more from Australians travelling overseas than we gain from foreigners coming here, so trapping that spending here benefits the economy. Third, we normally run a trade surplus in education of 2% of GDP but with the pandemic we only lost maybe half that as many foreign students went online. Finally, while the loss of immigration means lower long term potential growth it won’t necessarily impact per capita GDP (& hence living standards) or short-term recovery prospects (except for some sectors). So long-term the international border closure is a big deal, but it’s not so big short-term.

4. Covid is not over globally – but vaccines work

Which brings us to the basic problem that coronavirus is still not over globally. The good news is that new daily cases have fallen sharply in the last few months as vaccination ramps up. The bad news is that only 24% of the global population has had one dose. Even in developed countries where 49% have had a first dose, we are yet to hit herd immunity which may be around 80% fully vaccinated, and new more virulent strains (notably Beta, Delta and maybe Delta Plus) are causing problems with rising cases in the UK, Israel and Seychelles (where around 70% are fully vaccinated). In the UK, new cases are running around 18,000 a day which has caused a postponement to the final stage of reopening. But here is the really good news – while the vaccines are not completely effective in stopping people getting the new variants, the evidence suggests they are highly effective in preventing serious illness (which should minimise pressure on hospital systems) and death. So, reopening should be manageable once herd immunity is reached, even with coronavirus circulating in the community. But we are not at that point yet – so coronavirus still poses a risk to reopening in the US and Europe.

Which in turn highlights why Australia – which is further behind on the vaccine front with only 24% of the population having had one dose of vaccine – still has to be cautious in preventing coronavirus taking hold, and so has little choice but to continue down the snap lockdown/global border closure path to keep people healthy and to protect the economy from more debilitating coronavirus-driven lockdowns. Better to wait until herd immunity is reached and we can learn to live with a level of coronavirus circulating in the community rather than dropping our guard too early and having to learn to die from it.

With global vaccine production ramping up and more Pfizer and Moderna vaccines scheduled to arrive in Australia through the second half we should be able to reach herd immunity by early 2022. This is the only way to end the endless snap lockdowns in a way that does not risk Australians’ health and the economy.

Implications for investors

There are several implications for investors:

First, the ongoing threat posed by coronavirus and lockdowns will likely keep the RBA relatively dovish at its July meeting. While we expect it to stick to the April 2024 bond for its yield target and announce some tapering of its bond buying, it’s likely to reiterate that rate hikes remain a long way off.

Second, the threat from coronavirus setbacks is likely to limit the upside in bond yields in the short term.

Third, coronavirus setbacks are another potential trigger for a near term correction in shares and in cyclical stocks specifically. But if snap lockdowns remain relatively short as we expect, they are unlikely to de-rail the Australian economic recovery or the rising trend in Australian shares.