Introduction

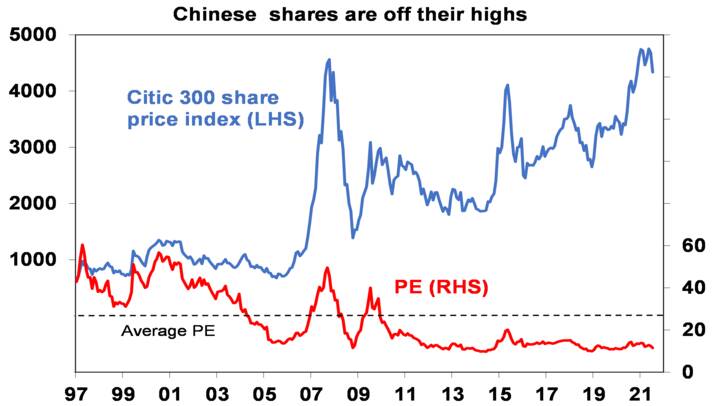

After surging 65% from its coronavirus low in March 2020 to its high in February this year, the Chinese share market saw an 18% decline into July. This reflected concerns about policy tightening, the economic outlook and a regulatory crackdown on a range of industries, notably tech stocks and steel production, with the latter contributing to a plunge in the iron ore price. So, what’s going on? How serious is the regulatory crackdown? What does it mean for China’s economic outlook and shares?

Regulatory crackdown

China’s regulatory crackdown has impacted multiple industries including internet stocks (like Alibaba & the Ant Group, Tencent and Didi with various anti-monopoly, financial regulation and cyber security investigations or scrutiny), private tutoring companies, property and online insurance. It has also recently restricted steel exports and announced a plan for “common prosperity.” The latter is focussed on growing the middle class, redistributing income, maintaining a large role for public ownership, and guiding public opinion on common prosperity.

What’s driving the regulatory crackdown?

China’s policy moves reflect a variety of drivers, in particular:

• Rising levels of income and wealth inequality. Similar to the US, China has high income inequality and low-income mobility between generations. There’s also an element of resentment towards billionaire moguls. If uncontrolled, these may threaten social stability as we’ve seen in the US.

• The three-child policy. China wants to boost population growth to support economic growth and reduce the burden of aging. A barrier to this is the high cost of education, particularly via private online tutoring which the government is seeking to regulate. Housing and healthcare costs may also be a target on these grounds.

• Concerns about social media and gaming. The recent US experience that saw social media exacerbate social unrest, social polarisation, and populism was no doubt observed by the Chinese Government. At the same time, social media and gaming are not seen as adding to productivity with semi-conductors and artificial intelligence (AI) a key priority. Hence the desire to regulate it more strongly.

• Concerns about big tech restricting small competitors.

• Poor housing affordability and rising household debt. This is the main factor behind regulatory moves in relation to property, eg, banks in Shanghai being instructed to raise mortgage rates. Curbs on the property sector may have a bigger impact this time around and are key to watch.

• A desire to boost the middle class. While the industrialisation unleased by Deng’s opening and reform from the late 1970s saw rapid growth and some get rich fast, the increasing focus over the last decade has been on quality growth and benefitting all with more social welfare. The focus on “common prosperity” is a continuation of that.

• Geopolitical tensions. Slowing social media may help free up resources needed for greater self-reliance in high priority areas like semi-conductors and AI (given US restrictions). Some of the recent action may also be aimed at reducing the reliance of Chinese companies on American capital and to protect Chinese data and technologies.

• Government control and financial risks. The growth of largely unregulated tech giants in China and relative decline of state-owned enterprises may undermine Communist Party control. The current leadership has been seeking to reverse this. Fintech companies offering payment platforms, lending and wealth management products threatened to further diminish that power and add to financial risks, and, as a result are now starting to be regulated like banks.

• Climate action. The move to restrict steel exports is part of this. The Chinese Government has long used directives like this to meet economic and social policies.

China’s policy moves towards greater government involvement in the economy are not inconsistent with trends in western countries since the GFC and the observation that the political pendulum is swinging back to the left after swinging strongly to the right with economic rationalist policies in the 1980s-2000s. Under President Biden the US will end up with a bigger government sector, while the last Australian Budget projected Federal spending stabilising at a level of GDP well above pre-pandemic norms. Western countries are also considering regulatory action against big tech. But of course, China is a communist country and a one-party state so its swing to the left seems more noticeable, particularly at time of geopolitical tensions with western countries.

What are the risks?

China’s reforms over the last decade have had mixed success – including the focus on de-leveraging and the introduction of a national property tax. However, Chinese policy campaigns often go on for several years so it’s too early to say that it’s over. The shift towards free market capitalism under Deng ran for 30 years or so, meaning the current shift towards big government (and more Communist Party control) could run for decades (as it could in western countries). The reforms face four main risks:

• Reduced ability to attract western capital – although they may be aimed at cutting reliance on foreign capital anyway.

• Reduced ability for Chinese tech companies to expand globally – eg Didi put plans to expand into Europe on hold.

• Reduced entrepreneurial spirit in China threatening longer-term growth, particularly after the crackdown on tech companies. Bigger government is not necessarily the best way to drive higher productivity growth in the long term – and that may also be an issue in western countries. A counter view though may be that the tech crackdown is not aimed at smothering big tech companies but rather at controlling them, that it will make it easier for smaller tech companies and boost competition and that reducing inequality, boosting population growth and the middle class will actually support long-term growth.

• Slower growth in the short-term. Reforms and the uncertainty they engender often come at the expense of short-term growth. While the Chinese government wants to focus on balanced growth and common prosperity, it also knows it must avoid significant economic weakness which could also lead to social unrest. As we have seen in recent years with the policies to reduce leverage, reforms are often paused if there is a short-term threat to growth.

China’s growth outlook

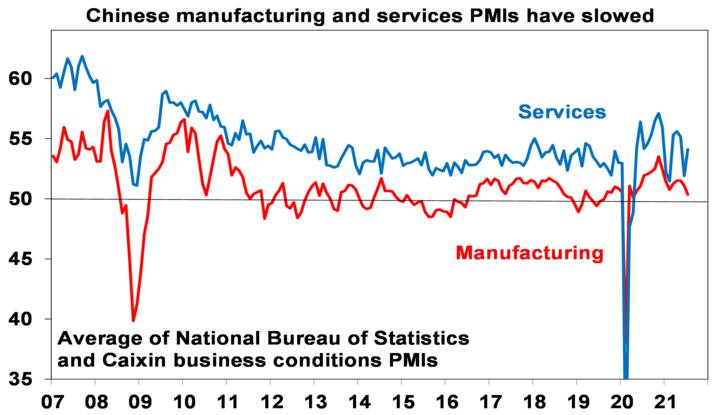

Which brings us to concerns about slowing growth in the near-term. After rebounding sharply from the lockdown last year Chinese economic data has slowed. Business conditions indicators (or PMIs) have been trending down.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

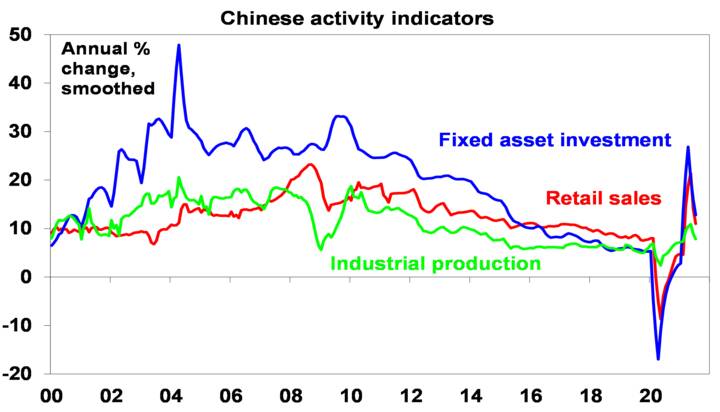

And industrial production, retail sales, investment, exports, imports & credit growth all slowed more than expected in July.

Source: Thomson Reuters, AMP Capital

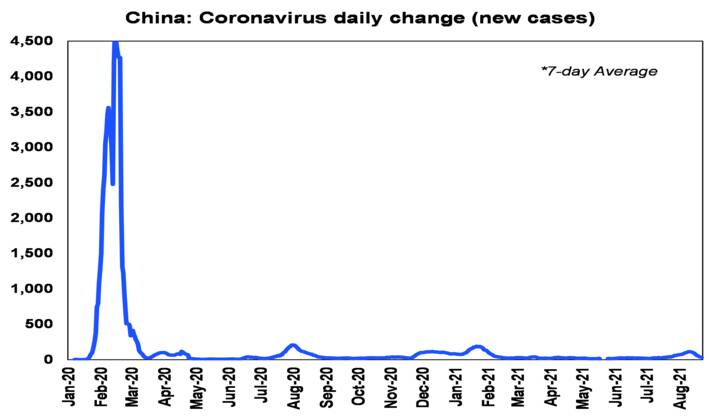

The slowing in annual growth measures partly reflects the drop off of the base effect boost as the 2020 lockdown slump drops out, but it has gone a bit beyond that as a result of floods, policy tightening after last year’s easing, increased covid restrictions due to a new Delta outbreak and carbon pollution reduction measures. As a result, September quarter growth is likely to be weak. A slowing in covid cases in the last two weeks may allow some easing of restrictions but they are likely to remain to some degree ahead of the Winter Olympics in February 2022.

Source: ourworldindata.org, AMP Capital

More fundamentally though the July Politburo meeting suggested some monetary and fiscal easing ahead and that the regulatory crackdown may go through a brief pause given the growth slowdown. In terms of the latter there has also been some indication of a slowing in anti-carbon pollution measures. As a result, growth is likely to accelerate again in 2022. After slowing to 4% year on year in the December quarter this year (from 7.9%yoy in the June quarter), growth is expected to accelerate to 6.5%yoy through 2022. Longer-term the trend is likely to be down in China’s growth rate as its period of rapid industrialisation and productivity growth is behind it.

The Chinese share market

The chart below relates to monthly data and so misses the extremes, but Chinese shares saw an 18% decline from their February high to their recent low. Valuations are not particularly onerous and will likely benefit from anticipation of stronger growth next year. However, regulatory uncertainty and geopolitical risks may constrain it on a medium-term view.

Source: Thomson Reuters; AMP Capital

Implications for Australia

A slowdown in China’s long-term growth rate and trade tensions impacting multiple Australian exports to China mean that the big boost to Australian exports from trade with China may be behind us. Over the last year it was offset by the surge in the iron price to over $US220 a tonne, but from its May high it fell by over 40% to its low last week, albeit to a still very high level. However, commodity prices don’t go in a straight line and some slowing in Chinese anti-carbon policies may see some stabilisation/short-term improvement in the iron ore price and it has had a bit of a bounce this week. Commodity prices generally should benefit from an upswing in Chinese growth next year, which should benefit Australian export earnings.