by Darren Williams and Guy Bruten

A single-minded approach to price stability is under threat as policymakers start to focus on what are—arguably—more pressing concerns. A shift in the inflation landscape is underway. But what will the new regime look like?

The notion of an “independent” central bank—where policy is set by technical experts, removed from the political process—has become one of the key tenets of good governance practice. But central banks do not operate in a vacuum. Ultimately, they will be judged by how much they help society achieve its goals. After the high inflation of the 1970s, the message for central bankers was very simple: keep inflation low. Central bank “independence” was a critical part of the political architecture to achieve that goal.

Now, that hawkish inflation message is blurring. The political balance is shifting, as governments try to repair the economic damage from COVID-19, combat inequality, make huge investments to mitigate climate change and manage record peacetime debt levels. Given these changes, what trade-offs will be applied? And will a return to the high inflation of the 1970s be the right template for the new inflation regime?

Not necessarily.

Several Moves Possible in the Inflation Endgame

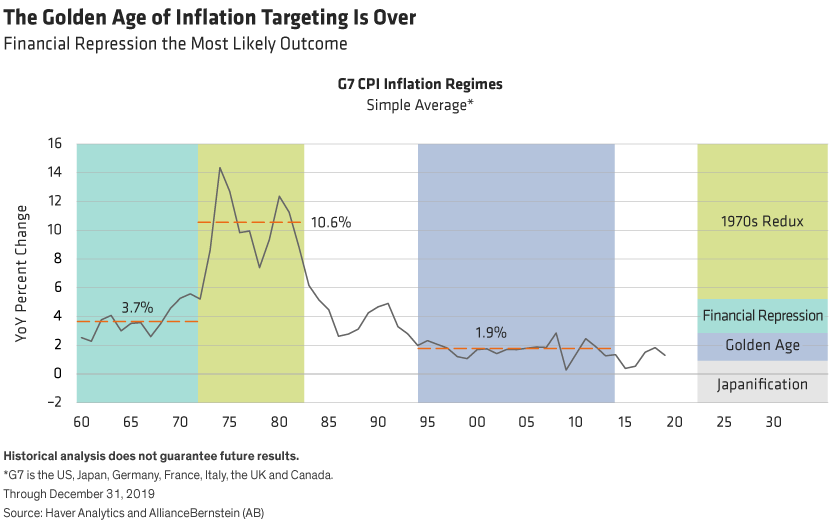

Since the end of WW2, there have been three distinct global inflation regimes, with Japan’s experience hinting at a fourth:

1) The immediate post-WW2 years, in which governments used fiscal policy to actively pursue their goals and mixed financial repression and inflation to help lower government debt

2) The 1970s, when inflation surged into double digits

3) The inflation-targeting era that started in the early 1990s, with widespread adoption of independence for central banks, formal inflation targets and the achievement of quasi–price stability (an annual inflation rate of 2.0%)

4) Japanification, with inflation fluctuating around zero and minimal levels of growth

Debt-Management Constraint Points to Higher Inflation Strategy

It should come as little surprise that we think the golden age of inflation targeting is ending. Too many of the factors underpinning that regime have changed. And inflation at 2.0% would make it very difficult to generate enough financial repression to help manage current debt levels.

The debt-management constraint helps explain why widespread Japanification is unlikely. Unless countries are willing to accept perpetual negative interest rates, managing high debt in a zero-inflation, low-growth world is an arduous task. Moreover, it’s not clear that other democracies possess the cohesive social structures and relatively low levels of inequality that have allowed Japanese society to cope with a sustained period of stagnation. The political challenge would be even greater with populism on the rise.

That leaves the two higher-inflation scenarios. Double-digit inflation is highly disruptive, unpopular and, as the UK historical record demonstrates, unusual. There is no support for very high levels of inflation, and we regard the 1970s redux scenario as unlikely—though inflation could, of course, temporarily overshoot to very high levels as the world transitions from one regime to another.

The regime that offers the best template for coming years is the post-WW2 period. Then, as now, fiscal policy gained dominance, and containing inflation slipped down the pecking order as governments began to pursue broader objectives. There was also widespread use of financial repression to help manage government debt—and “financial repression is most successful in liquidating debts when accompanied by a steady dose of inflation.”* Crucially, as former Chair of the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) Arthur Burns noted in 1979,† inflation at these sorts of levels is still low enough to be seen as an “acceptable” price to pay as society starts to pursue broader objectives.

Policy Choices Will Shape the Inflation Outcome

Does this mean that central banks will become cheerleaders for this new, modestly higher inflation regime? That’s unlikely.

Several prominent economists have made the case for higher inflation targets, and the Fed has adopted a new average inflation-targeting strategy—albeit one that’s still anchored by a focus on long-run inflation expectations. But focusing on publicly stated targets misses the point. Few (if any) historical episodes of high inflation started out as deliberate attempts to drive the price level higher. Instead, inflation arose indirectly as policymakers pursued other goals. We expect the same thing to happen in coming years.

Just as in the 1960s and 1970s, it’s hard to see how central banks can avoid being caught up in these shifting “philosophic and political currents,” as Arthur Burns called them. The temptation to bend a little, in order to accommodate the prevailing political winds and yet still stay in the game, will be great.

The new regime is unlikely to be a carbon copy of the double-digit inflation environment that emerged in the 1970s. A more probable template is the financial repression era that ran from WW2 through the 1960s. But some elements of the backdrop today are clearly different. Notably, economic growth was far stronger in the immediate postwar years than it is now. That has clear ramifications for hitting some of those alternative objectives. For example, to drive debt/GDP ratios down, interest rates need to be lower and/or inflation higher than they were during the earlier financial repression period. That sort of uncomfortable arithmetic reinforces our conviction that, in the end, the political landscape, and the policy choices this entails, will open the door to higher inflation.

* Carmen M. Reinhart and M. Belen Sbrancia, “The Liquidation of Government Debt” (working paper, International Monetary Fund, 2015)

† The Anguish of Central Banking, 1979

Darren Williams is Director—Global Economic Research and Guy Bruten is Chief Economist—Asia-Pacific at AllianceBernstein (AB).