by Paul Ehrlichman and Grace Su

Historical Context

China has embarked on an ambitious reform agenda based upon four key themes. First is to build a modern regulatory and tax architecture driven by the central government. Second, create an economy driven by robust domestic demand while supporting higher value-added exports and foreign investment. Third, address inequality via measures aimed to promote “common prosperity.” Finally, encourage family happiness, sound values and more children. These policy shifts are important in framing the present correction in Chinese share prices, the Evergrande insolvency and potential contagion effects for the global economy and markets. As always, it is good to remember that, unlike freedom or liberty in the West, China’s highest ideal is “order.” Therefore, many of the actions are designed to restore balance and are prudential in nature.

The residential housing market is touched by all the key reform areas. The property sector has a history of powerful regulatory changes and has been at the center of economic policy for over 30 years. In 1988, the Chinese government changed the constitution to allow the right to use land that could be bought and sold under long-term leases. This was a significant source of funding for the massive infrastructure investments over the past decades. Then, in 1998, when most urban dwellers lived in employer-provided residences, they removed the obligation of state companies to provide housing. Companies sold the existing flats at heavily discounted prices, creating a large store of “private” wealth and setting off a boom in residential real estate. Companies took advantage of the rise in housing prices and activity by creating property subsidiaries, but in 2010 the central government mandated that they fully divest these businesses. Evergrande grew out of this wave of development, publicly listing in 2009, with ever-increasing scale, scope and leverage.

More recently, the government has restricted access to funding for companies that crossed “three red lines” related to balance sheet strength and debt levels. Consequently, Evergrande, highly leveraged and consistently cash burning, faced a rising cost of capital in the public debt markets and was rated as “junk.” As Evergrande is the largest property company in China, signs it was experiencing a liquidity crisis spread concern to other weak peer firms, which led to a sharp decline in junk bond prices. Sentiment toward Chinese shares was already quite negative given recent actions taken to reform the large tech firms and the private education sector. The economic outlook has also deteriorated due to the rise in COVID-19 infections, especially in Asia where cases were previously at a low level.

Sustainability-Driven Revenues Are Maximizing Value

As Ray Dalio recently noted in discussing the Evergrande situation, “Investors will be stung — that’s how it works.” The collapse of China’s largest developer is obviously painful, but this cost will be borne by investors and lenders. The government will use this as an example and policy tool to address speculative excesses in the property markets and highlight risks to investors. Meanwhile, China seeks to encourage investment in diversified capital markets, including municipal bonds, corporate credit and equities. As a result, while they will prevent losses for citizens that have deposits on unfinished houses, the government will allow market forces to determine the ultimate resolution of Evergrande’s assets and liabilities. Thus far, markets appear to be properly pricing in such risks, with Chinese high-yield debt offering a significant positive real return. Compared to the U.S. and Europe — in which non-investment-grade corporate credit offers a negative real yield — it is arguable now where the risk of loss is greater.

The Evergrande default is not likely to create a “Lehman” cascade of events. Prior to insolvency, Lehman was an investment grade credit and highly-rated prime broker with paper held broadly by a number of money market and hedge funds. Evergrande has been considered “junk” for several

years, which limits exposure of the broader financial system. Loans to the troubled developer just 0.17% of total loans and 0.6% of local banking assets. Dollar-denominated liabilities represent only $18 billion of $300 billion in total debt. In short, Evergrande should remain a locally contained problem and not the start of a new global financial crisis.

Evergrande’s default is the direct result of reforms and therefore the main risk that we are focused on is the broader property sector. Real estate is the largest store of wealth in China and represents, directly and indirectly, close to 30% of GDP. The unintended consequence of deleveraging the property sector might be to decrease confidence that prices will rise in the future. This could create a significant headwind to economic growth. Our sense is that the government is attentive to this and does not seek to drive real estate prices lower, but the risk of a policy misstep remains.

Overall, Chinese reforms are viewed positively by the people and should benefit favored sectors and overall consumption. The goal remains to double per capita GDP in the next 15 years, which could be accomplished with growth between 4% and 5%. The current uncertainty and risks should be viewed in the context of the significant long-term opportunities in China.

Greater Scrutiny on Macau Gaming Industry

In contrast to the property, technology and education sectors, the gaming industry was already highly regulated and subjected to significant reforms. The sharp drop in share prices appears to be an overreaction to the normal calendar of regulatory review and policies put into place several years prior. The government seeks to encourage development of Macau and Cotai as a domestic and regional tourist destination and is unlikely to materially harm the existing operators. Clearly, they desire a better balance between gambling-related and non-gaming revenues, as is the case in Las Vegas. As a result, we view the gaming stocks, especially the locally-owned companies, as attractive long-term investments.

Specifically, we do not believe the Chinese government was necessarily singling out the Macau gaming industry as a “common prosperity” violator as it did with the education and tech sectors. Macau’s gaming concessions were set to expire in June 2022, and so the process to renew the concessions needed to begin around now to enact new laws before the expiry.

Prior to the official re-tendering announcement last week, market participants already expected there to be uncertainty around the number of concessions, grant period, tax rate and other capital investments that the government would be keen to require. What surprised the market, however, was additional language around more local ownership of the casino operators (or government representation on the boards) and potential restrictions on dividend payouts. Given the negative sentiment toward the heavy hand of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) of late, investors were quick to bail despite hardly any details being discussed yet.

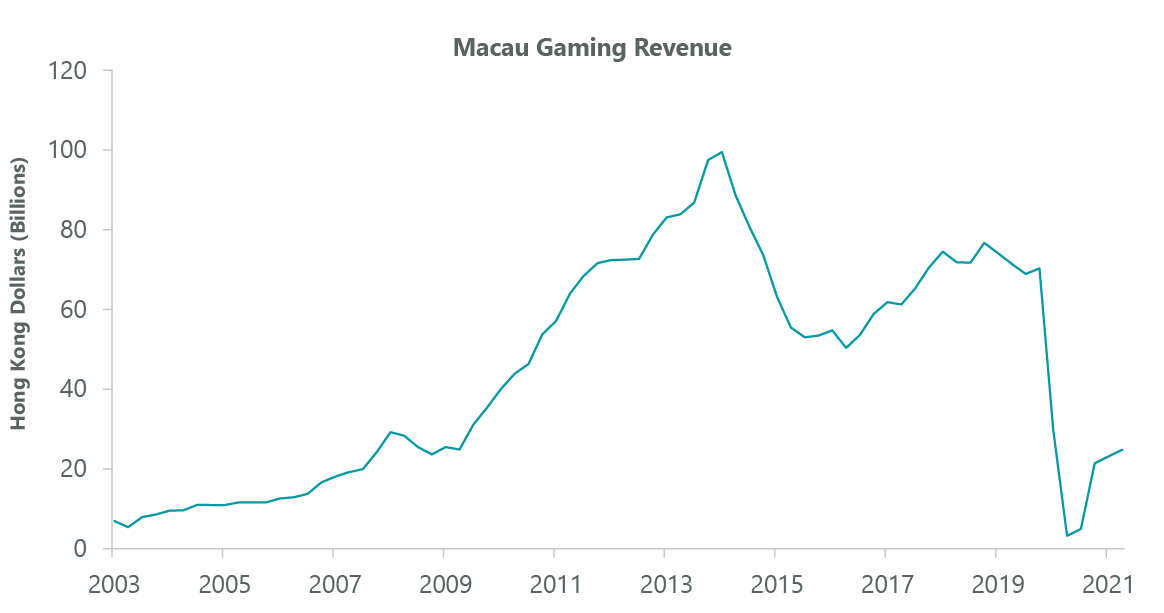

Exhibit 1: Macau Has Developed into a Leading Gaming Destination

Data as of June 30, 2021. Source: Bloomberg.

Our sense is there was a bit of overreaction, and there are many ways in which the gaming operators and governments’ interests are aligned, with the common goal of building the world’s premier tourism hub in Macau. Since the industry was liberalized nearly 20 years ago, casino operators have been the largest infrastructure investors, employers and taxpayers to the Macau government. This is very different from the education and tech sectors, where a small handful of entrepreneurs amassed significant wealth without reinvesting in local communities.

For Macau to continue to develop at its historical pace, we believe the government needs private sector involvement, and both parties will ultimately negotiate a mutually beneficial outcome for the coming few decades.

Outlook

Generally, the government is experienced in winding down insolvent firms and will reallocate the assets of weaker developers at the expense of bondholders and equity investors. This shakeout is expected to continue into the first quarter of 2022 — but is happening in the context of a still-strong property market. In August, property sales were 14% above the average of the 2015–2019 period, with most cities experiencing rising prices and inventories close to historic low levels.

The combination of rising COVID-19 fears, uncertainty around the pace of central bank “tapering” and China’s reforms have led to the general underperformance of economically dependent shares over the past three to four months. We believe this is a misreading of recent moderation in the short-term pace of economic activity as investors remain anchored to the secular stagnation dynamics we have seen since the Global Financial Crisis. Central banks and governments are aligned in addressing inequality and encouraging growth in the real economy along with the investment demands of the long-term energy transformation. Also, the negative impact of the global pandemic will likely lessen next year, adding to economic activity. We are experiencing a period of supply constraints, not insufficient demand, with a profoundly supportive policy backdrop. Consequently, even in the face of short-term headwinds from China, we remain in the “stronger for longer” camp versus a return to secular stagnation.