by Andrew Mulliner, CFA – Head of Global Aggregate Strategies / Portfolio Manager

The last few weeks have seen a sharp sell-off in sovereign bond yields globally, with central banks’ ability to be “patient” tested by higher inflation. After the rally seen in July, where the US 10-year yield fell to around 1.2%, we considered that government yields in core markets were at the bottom end of their fair value range, with risks skewed towards higher yields as we moved into the end of the year. The speed of the move has been faster than expected with the September round of central bank meetings. With bond yields rising across sovereign yield curves and breaking out of their previous ranges at certain maturities in the US (2 and 5 years) and in the UK (2, 5 and 10 years), the move has accelerated.

The Fed’s September meeting takes a more hawkish tone…

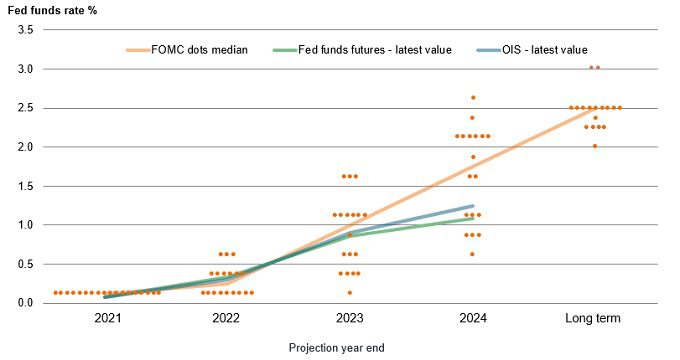

The September meeting of the US Federal Reserve (Fed) brought a new set of economic projections, which revised inflation forecasts upwards for this year and next, and a more hawkish tilt to the dot plot. Half of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)’s voting members now expect a single rate hike by the end of next year and the fed funds target rate may climb back to 1.0% by the end of 2023 (see figure 1).

Figure 1: the Fed’s latest dot plot and implications for fed funds rate

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as at 1 October 2021.

Chairman Powell also expressed some confidence that the tapering of US Treasury and mortgage‑backed securities (MBS) purchases could be completed by the middle of next year. However, he made clear that “the timing and pace of the coming reduction in asset purchases will not be intended to carry a direct signal regarding the timing of interest rate lift-off”. So, there will be some clear air between the end of tapering and the first rate hike, but it is clear that the balance of risks have shifted and there is considerable uncertainty how long transitory inflation factors will last.

…the next day, Bank of England adds to the hawkish message

The Bank of England (BoE)’s meeting the day after the Fed’s added to the hawkish message. UK government bond yields had been rising since August, but the front end of the yield curve in particular moved to price in a more aggressive hiking cycle. The central bank said the case to tighten UK monetary policy is building: there was increasing evidence from global and domestic cost and price indicators that inflationary pressures were likely to persist; realised inflation may breach 4% in the near term and, with the existing policy stance, inflation was likely to remain above the 2% target in the medium term. As a result, the market is now (1 October 2021) pricing the bank rate (BoE’s base rate) to reach 0.5% by mid-2022, with one further hike to 0.75% by mid-2023 before levelling out, with the next hike to 1.0% priced by the end of the decade.

The BoE’s commentary on sequencing between quantitative easing (QE) and rate hikes was strengthened, when it stated that rates will be the main policy tool and can start to rise even before the end of the QE programme. By de‑linking QE and the bank rate, there is more onus on using the bank rate to manage the cycle, and will result in a smaller balance sheet (of asset purchases) over the long term. It also confirmed that in the first instance it would allow maturing gilts to run off rather than engage in actively selling holdings, which would only take place after a 1.0% bank rate is reached.

Despite the higher rate expectations, sterling has struggled to rally as the UK economy finds itself potentially in a stagflationary1 environment. The BoE has to begin to tighten policy into weaker growth and a supply side inflation shock, exemplified by the dramatic moves higher in inflation break-evens this week (now through 4% on the 10-year retail price index swaps – figure 2).

Figure 2: dramatic moves higher in inflation expectations in the UK

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as at 6 October 2021.

Note: 10-year GBP Inflation Swap RPI Zero Coupon – the swap, based on the retail price index (RPI) in the UK, is commonly used by investment professionals for hedging purposes and is reflective of (or a measure of) the breakeven rate of inflation (ie, market expectations for inflation).

The calculus of risks for central banks is finely balanced

Similar to the central banks, we expect that many of the factors driving higher inflation presently will abate through time, we are mindful that supply chain challenges in particular have lasted longer than we had initially anticipated. With high prices expected to continue into the summer period, and into 2022, this leaves the calculus of risks for central banks finely balanced. On one hand, high prices will likely act as a drag on economic growth and should therefore abate as either demands drops to equalise with constrained supply, or supply eventually picks up. On the other hand, extended periods of higher prices pose a risk to the unanchoring of inflation expectations, which may result in a more persistent inflationary environment.

Central bankers are generally cautious creatures, but clearly the current environment has tilted their attitudes in a more hawkish direction and bond markets are in the midst of repricing to reflect this shift.

1 Stagflation: a relatively rare situation where rising inflation coincides with anaemic economic growth.