As vaccination rates increase around the world and we (hopefully) return to some normality in our daily lives, world economies appear to be stabilising. Economic output is near or above pre-pandemic levels, and signs of inflation and wage pressure have become a theme of 2021.

As a result, many investors and commentators are now keeping a close watch on the US Federal Reserve and any change in current monetary policy: specifically, the quantitative easing program (QE) and the potential that the monthly asset purchases (US$120bn per month) will begin to slow, or ‘taper’.

Some investors have bad memories from the last time the US Fed tapered, and as such there appears to be some anxiety over the next central bank move. Indeed, in the minutes from last month’s meeting, the committee stated, “Most participants noted that, provided the economy were to evolve broadly as they anticipated, they judged that it would be appropriate to start reducing the pace of (asset) purchases this year”.[1]

Should investors fear the taper?

Some historic perspective

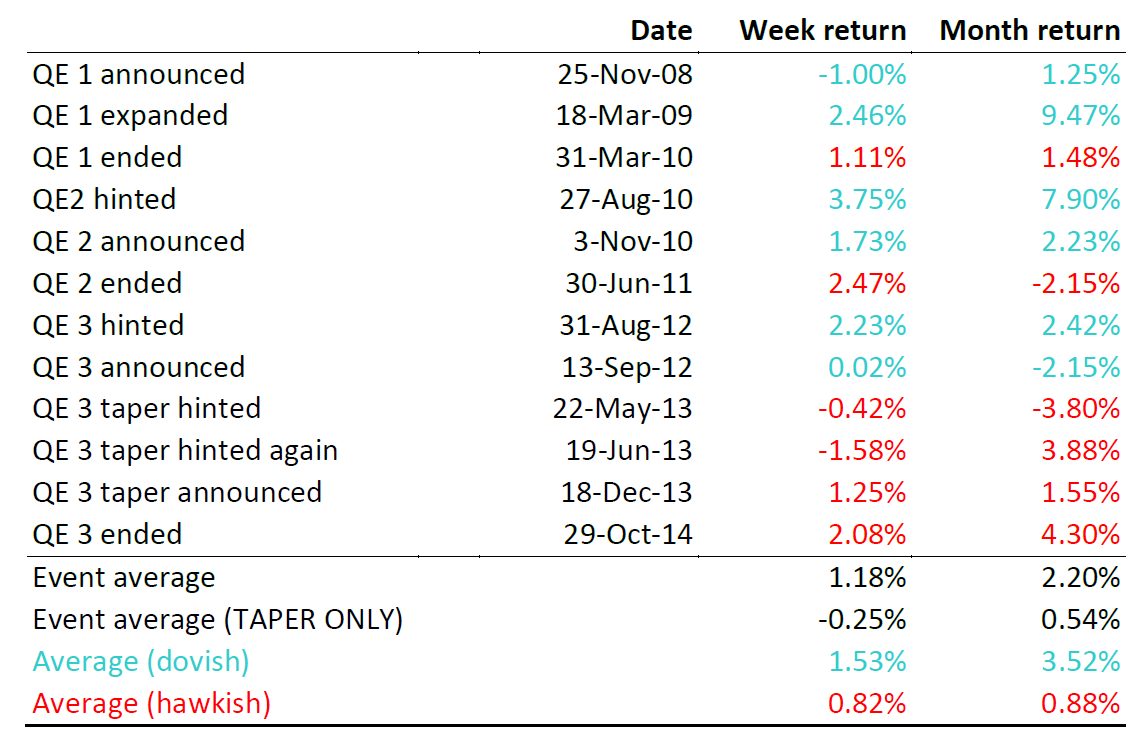

Since the great financial crisis of 2008/2009, there have been three QE programs in the United States: two of which ended abruptly, and the third via taper (a gradual reduction in monthly asset purchases). The following table highlights the dates of each announcement (or signalling) of these policies, and measures the performance of the S&P500 Index in the week and month following these announcements.[2]

Source: Calculated Risk, Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors

To assist our analysis, we have colour-coded each ‘QE event’ depending whether the policy announcement was dovish (supportive of the economy and more QE) in blue, or hawkish (restrictive and less QE) in red. The taper – which was first hinted at in a speech by Ben Bernanke on 22 May 2013 – set a clear path to the end of QE and led to the first post-GFC rate increase in December 2015.

The data clearly shows a ‘dovish’ Federal Reserve tended to be good for stocks over the following week and month (on average up +1.53% and +3.52% respectively). However, it is also clear the end of QE (on average) is not necessarily bad for equities (on average up +0.82% and +0.88%).

Most of the taper angst appears to be derived from the May 2013 statement to US congress by then-Chairman Ben Bernanke, when the concept of gradually reducing asset purchases was first suggested.[3] Unlike the end of the first two QE programs, this signalled a change in policy, and introduced ‘the taper’ for the first time.

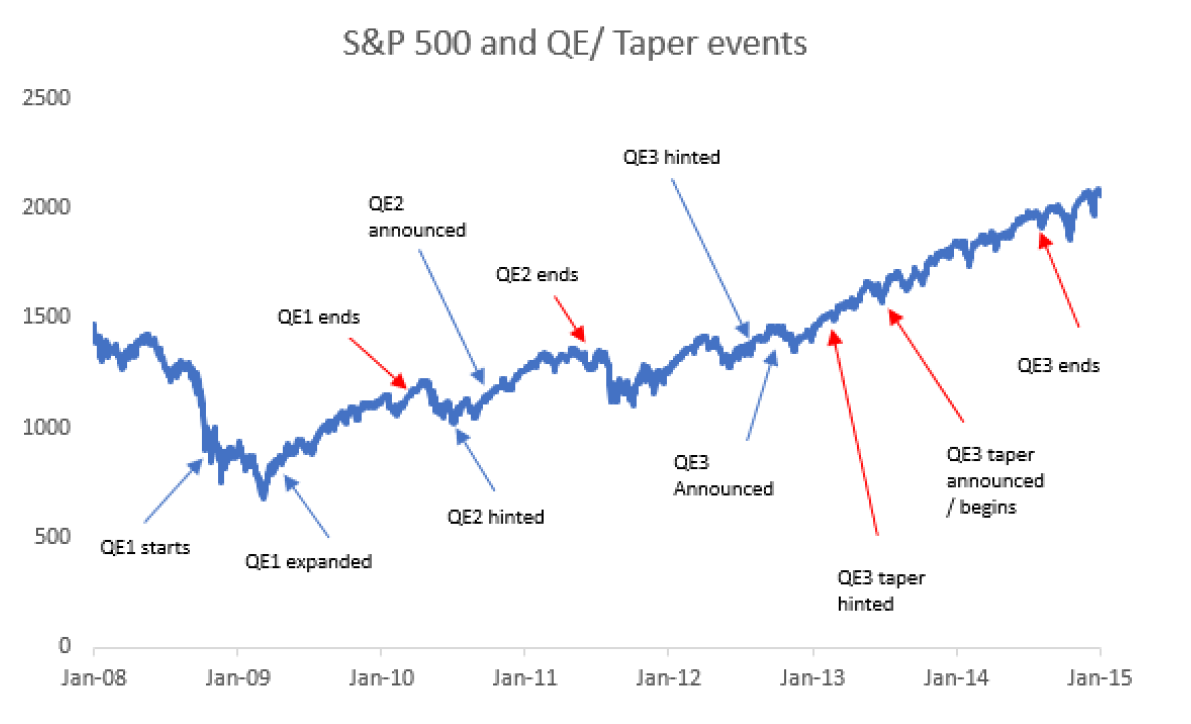

Yet in the current environment, this moment has already passed as per the September minutes. And based on historic performance, the idea that we should worry about any taper carries very little historic weight. Moreover, for investors not concerned with short-term performance, the best strategy post-GFC was to ignore the taper/QE noise entirely and simply stay invested.

Source: Bloomberg, Calculated Risk, Quay Global Investors

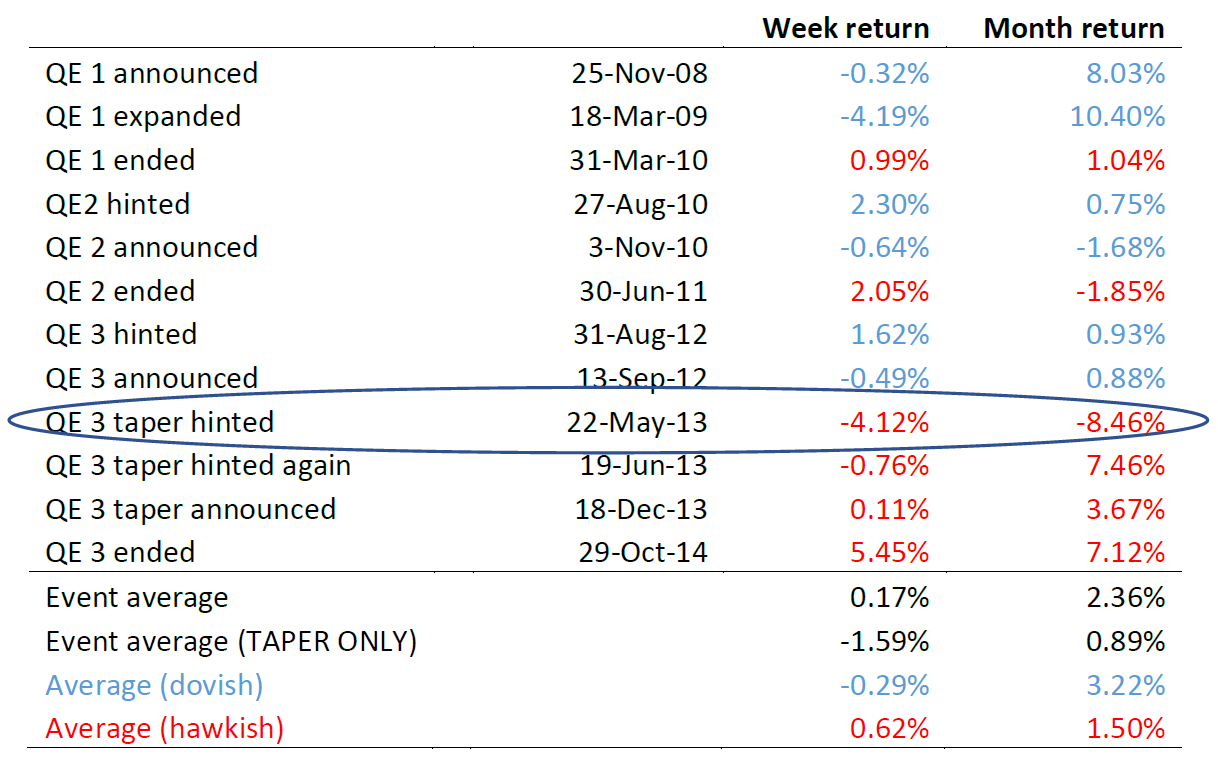

What about real estate?

Listed real estate was not immune to the volatility caused by various quantitative easing announcements. However, the data again suggests there is little to fear with respect to any end to the QE program – although admittedly, there was more volatility.

It would probably surprise some investors that global real estate did worse over the week after the Fed was dovish (-0.29%), compared with when it was hawkish (+0.62%). And like the S&P500, on average global real estate actually performed well in the month following the various taper announcements (+0.89%), and following hawkish statements (+1.50%) .

Source: Calculated Risk, Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors. Returns based on the FTSE EPRA/NAREIT Index unhedged (AUD)

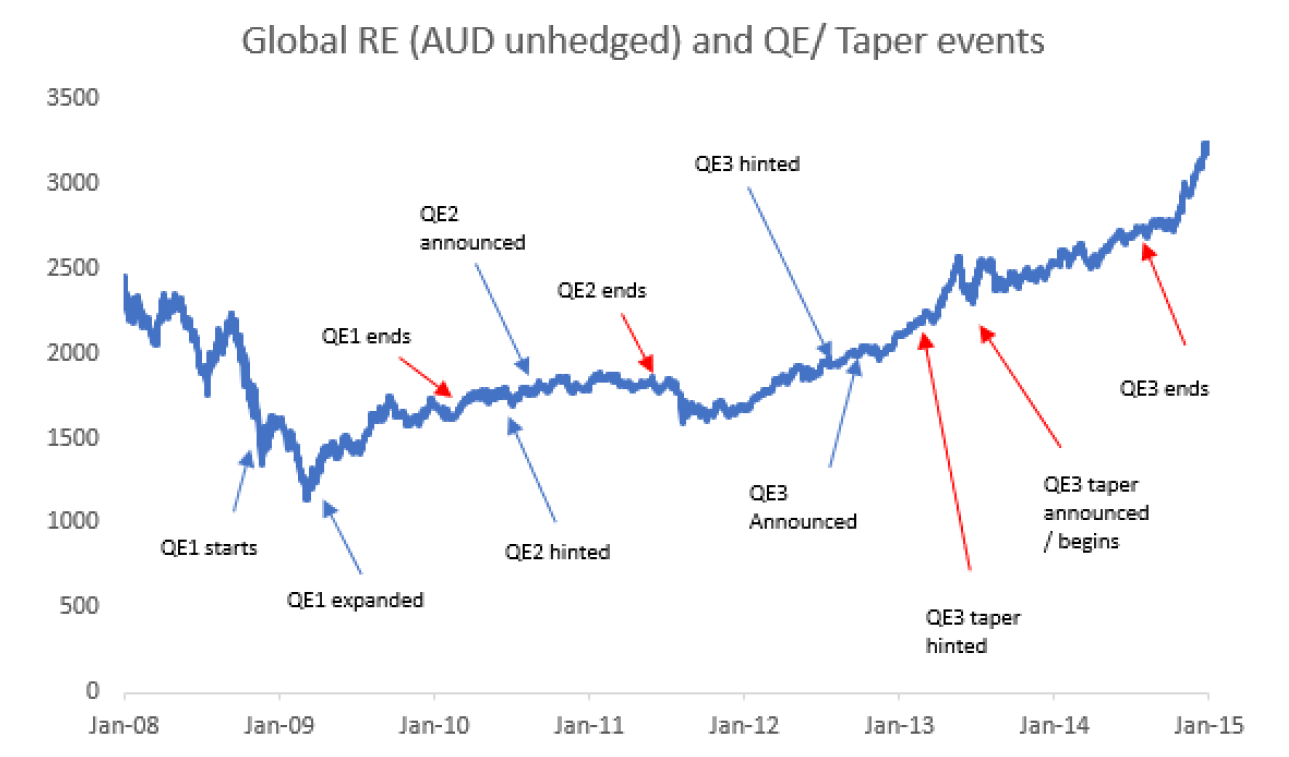

Again, as the following chart shows, long-term investors in global real estate that ignored the noise were rewarded over time. We also make the observation that global listed real estate performed best during and after the Fed became consistently hawkish following the initial taper hint in May 2013. This again should remind investors that real estate does best when the economy is good, not when interest rates are low (or central banks are dovish). For more on this, refer to our 2019 article 30 years of investment lessons from Japan.

Source: Bloomberg, Calculated Risk, Quay Global Investors

Why QE has less impact on equity markets than most think

A common narrative post financial crisis was that various central banks (across the world) influenced equity markets directly or indirectly with their various monetary programs – especially quantitative easing. Throwaway lines such as “flooding the market with liquidity” or “artificially reducing interest rates” or “forcing investors into risky asset” played well with the CNBC/Zero hedge crowd, but rarely are these comments scrutinised for the detail.

The reality is that central bank influence on equity markets valuations is minimal at best, for the following reasons.

- Central bank asset purchases are nothing more than an asset swap, where central banks buy low risk assets (government bonds) in exchange for low risk cash. Zero net financial assets are added to the private sector via this process. No new money is created; QE only alters the term/duration of money held by the private sector. So the idea that QE is ‘money printing’ is very deceptive, and borderline false. For more on this, refer to our 2016 article Are central banks losing their effectiveness.

- The unit of account for central banks, generally called reserves (in Australia they are known as exchange settlement balances) is not legal tender for the purchase of everyday items. These balances (also known as inside money) simply provide member banks with liquidity to settle customer transactions via the inter-bank market. Money issued by the central bank cannot buy shares – or even a stick of chewing gum for that matter. For more, refer to our 2020 article Thinking about liquidity.

- The general idea that owners of high quality, very low risk bonds are prepared to exchange this risk profile for higher risk equities on a whim makes little sense. Bond markets (especially US bonds) are always highly liquid – investors do not need QE to convert bonds to cash. Or put another way, bond funds and their low-risk clients don’t become equity funds overnight because of QE.

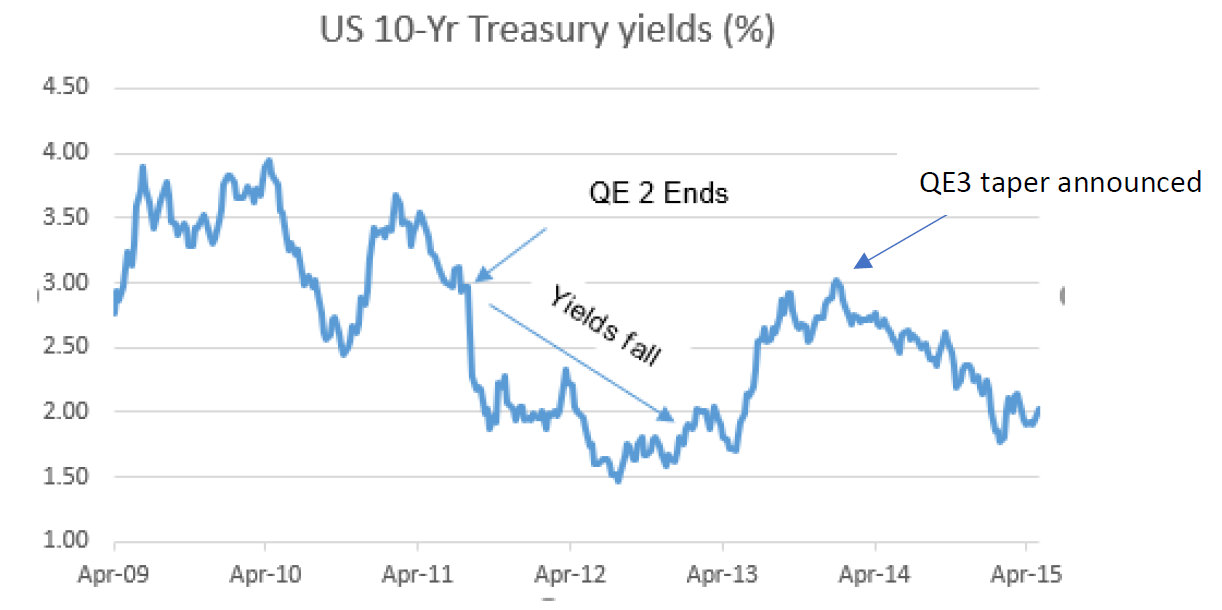

- There is very little evidence QE supresses interest rates, artificially or otherwise. In fact, the opposite seems to be true. Since QE is seen as stimulus, it elevates interest rates higher than would normally be the case. And when it is withdrawn, long bond yields generally fall – as happened after QE2 ended in June 2011, and after the QE3 taper announcement in December 2013.

Source: St Louis Fed, Quay Global Investors

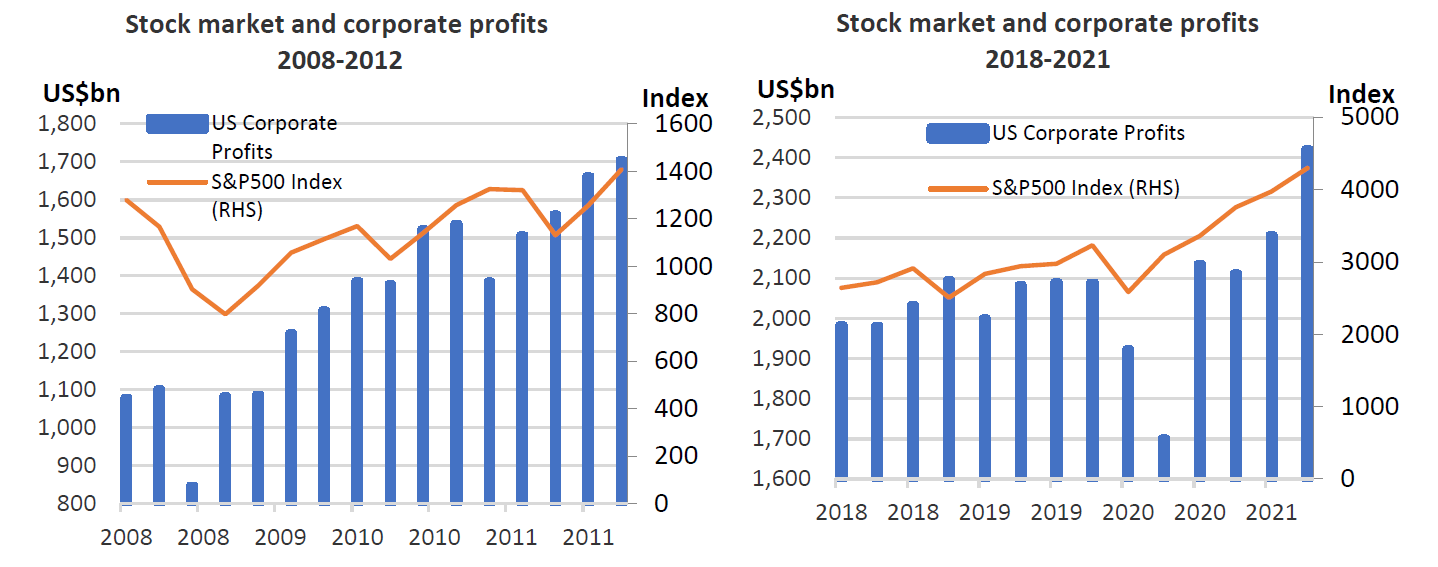

It’s all about profits

As we have stated in previous articles, what drives long-term equity returns are profits. And while some investors blame (or credit) central banks for share market performances, on most occasions equity performance is supported by rising earnings. As we highlighted in our June 2021 article Checking in on Kalecki, the macroeconomic source of company profits is more closely aligned to fiscal policy (spending and taxing), not monetary policy.

Source: St Louis Fed, Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors

Concluding thoughts

At Quay, we are unapologetic in our bottom-up approach. This does not mean we ignore macroeconomic data or various government policy. The key is understanding which macroeconomic issues matter. The US has now enacted various forms of QE over the past 12 years – and not unlike the Japanese experience (now 20 years of QE), the data suggests worrying about central bank policy and actions is not productive for long-term investors. That’s not to say equity markets are not overvalued; but if they are, it has more to do with animal spirits than the Fed.

Our observation is investors should spend less time worrying about central bank actions that have very little impact on equity markets beyond a placebo effect – and more time remaining invested in high quality companies that grow cashflows sustainably over time.

Download a copy of this article HERE.