by Robert M. Wilson and Robert M. Almeida

Demand for risk assets has been historic in 2021, with greater inflows into global equities this year than in the past 19 years combined, according to a November 24 report from Bank of America. The bank also notes that a third of that demand has been for stocks carrying an ESG or sustainability label, and similar dynamics have played out in credit markets.

In our experience, many investors today believe corporate sustainability is the ultimate win-win. They contend, for example, that if employers pay their workers more it will result in higher sales and productivity and ultimately reduce costs. They also maintain that cutting emissions will not only help the planet but also bolster companies’ bottom lines.

That is true for some companies that are already operating in a sustainable manner or have the means and ability to adapt to a changing world. But for many companies, change will prove risky and expensive.

In recent decades, many less-than-competitive, shareholder-focused enterprises with undifferentiated products or services have extracted rent from the environment, suppliers, workers, bondholders and others. The rise of sustainability suggests those economic levers are likely to recede and will probably reverse, leading to pressure on corporate profit margins and income statements. We fear that short-term investors underappreciate how many companies have a real terminal value problem.

Sustainability isn’t free, and in our view, efforts to become more sustainable will challenge many firms and perhaps even bankrupt some.

Accelerating trends

The pandemic accelerated many well-documented secular trends such as digital media, cloud computing and work-from-home arrangements, but it also hastened less obvious ones, such as loneliness, wealth inequality and interestingly, investor demand for changes in corporate behavior.

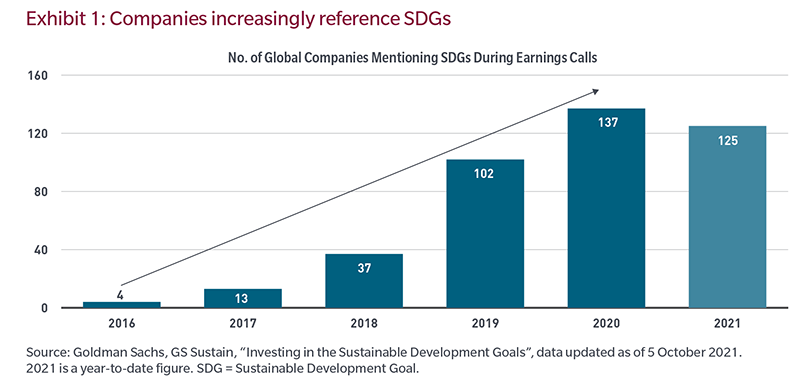

That has resulted in a growing recognition among management teams of the need for more sustainable business practices. This is illustrated in Exhibit 1, which looks at the number of global companies that referenced during earnings calls any of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, a set of global objectives agreed on by the UN General Assembly in 2015 to improve the quality of life worldwide. Clearly, companies are getting the message.

Why does this matter?

There is a long list of reasons why civil society, governments and special interest groups have been concerned with ESG issues. Most notable, of course, is that addressing them is critical to the long-term success of our global community. For example, runaway climate change or income inequality could have profoundly negative societal ramifications.

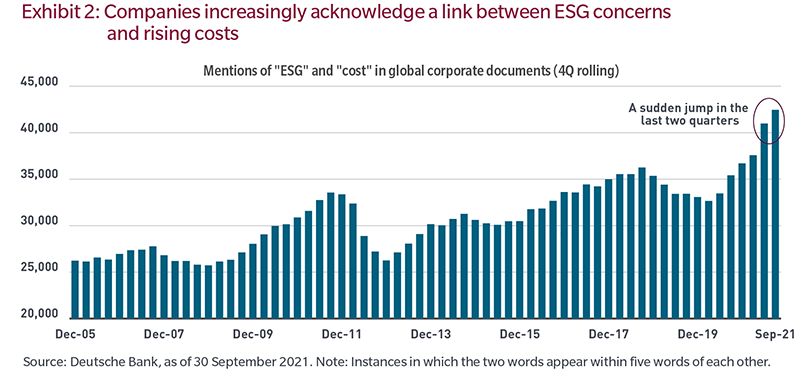

Unsurprisingly, investors and management teams have begun to pay attention because of how these considerations will flow through to the income statements of companies worldwide. Interestingly, we’re starting to see links emerge between interest in addressing ESG issues on one hand and financial factors on the other. For example, corporate concerns over rising costs appear aligned with a recent surge in references to sustainability issues in company documents.

Materiality is key

Sustainability will drive new business opportunities for some while exacerbating risks for others, leading to substantial divergences in the long-term enterprise value of many companies. But what is often lost in the current ESG narrative is financial materiality, which naturally affects asset prices.

While the global labor shortage is seemingly a function of the pandemic and stimulus, it’s also part and parcel of the broader ESG movement. Beginning a few decades back, increased globalization and robotics gave corporations an advantage over labor. But in the last business cycle, where policymakers lowered rates to the zero-bound to promote hiring, CFOs opted for buybacks instead, culminating in the widest levels of income inequality of our lifetimes as investors got rich and the economy and labor were left behind. Now the tide has turned and labor is pushing back, demanding higher wages and getting them. We shouldn’t be surprised.

In the current environment, producers of fossil fuels and products reliant on their use also face high hurdles. Many in the oil industry are banking on a growing middle class in emerging markets to underpin demand and help maintain the status quo. However, over two thirds of oil demand is tied to automobiles powered with internal combustion engines, which we believe will become antique in the not-too-distant future. Cumbersome organizations that are slow to adapt to change are unlikely to survive.

Looking back over the past 100 years, one thing is clear: Industry incumbents don’t fare well in the face of disruptive technologies. The move toward sustainability is a disruptive force akin to the industrial revolution or the advent of the Internet. It will define society and the investment landscape for decades. But it won’t be free. There will be some winners and some very big losers. And this new paradigm is unfolding when risk premia are at all-time lows, making the responsible allocation of capital even more important.