Factors, such as value, are identifiable, persistent drivers of risk and return. Up until recently, investors had to rely on active fund managers to achieve their investment objectives. Active fund managers have often utilised ‘factors’ as a key part of their investment process to identify companies worthy of investment.

More recently investors have been questioning their reliance on active managers and seeking passive alternatives. Apart from active management being more expensive than passive investing, active management also introduces other risks such as key man risk and investment process risk. One of the beneficiaries of the rise of passive investing has been the growth of ETFs.

ETFs have revolutionised factor investing. There are now many low cost ‘smart beta’ ETFs which deliver the ‘factor’ (or ‘smart’) returns beyond the market benchmark (or ‘beta’). They do this by tracking smart beta indices which are specifically designed with targeted investment outcomes in mind.

To understand this innovation, it is worth understanding where investing has evolved from.

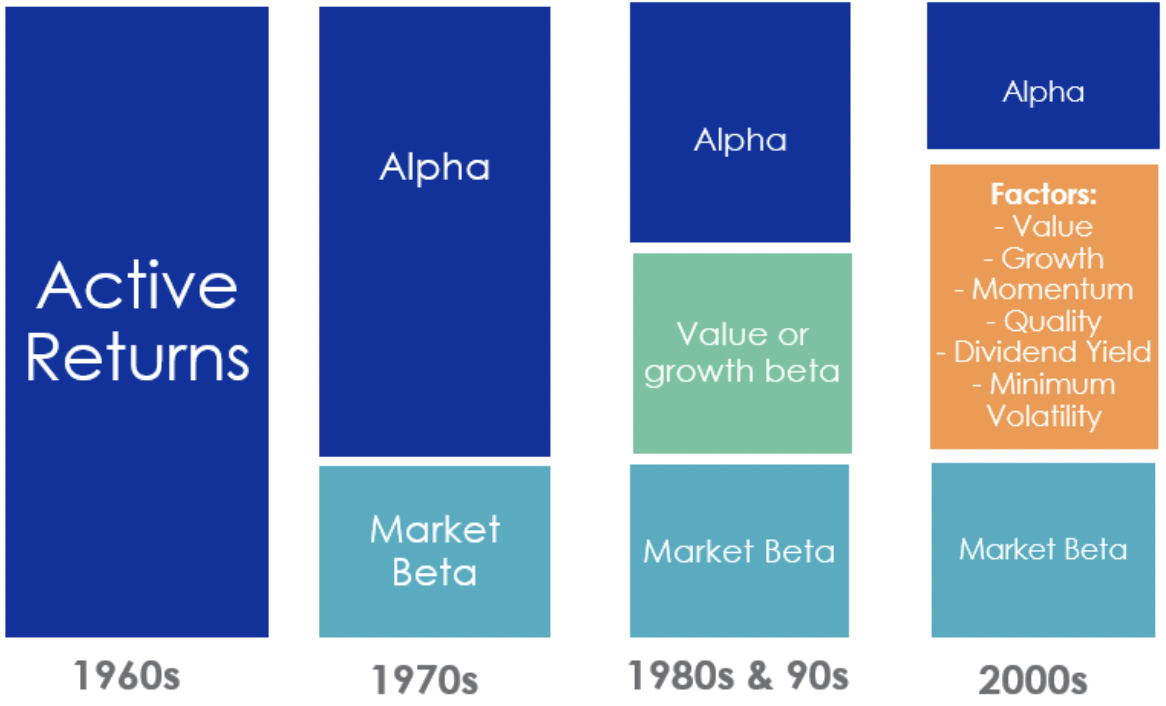

You may have seen this diagram, or an adaptation of it, before:

Source: VanEck

Or maybe you haven’t. It illustrates how returns have been attributed to professional active investment managers’ funds over time as more and more data became available.

Back in the 1960’s an active manager’s return were compared only to other active manager’s returns. Whoever had the highest return was the most skilful.

Toward the end of the 60’s, as research by Harry Markowitz and William Sharpe emerged, market capitalisation indices become the standard measure of the stock market. It was against these barometers active managers’ returns, and the standard deviation of those returns, were compared. The Greek alphabet became the lexicon for this.

‘Alpha’ is the term commonly used to describe performance above a given benchmark market capitalisation weighted index. ‘Beta’ refers to the performance of the market represented by that index. For example, in Australia the standard market benchmark, and therefore the standard measure of beta, is the S&P/ASX 200 Index. Returns in the 70s, were attributed the returns that were the result of the market, or beta, and the fund manager’s skill, or alpha.

In the 80’s and 90’s, following more empirical research and analysis of portfolios, stock pickers were described as: value managers; growth managers; or GARP (Growth at a Reasonable Price) managers – which is a combination of value and growth. Value managers were those that focused on identifying stocks which were trading, at what they believed, was a discount to their fair value. One way to identify value stocks is to pick those with a low price-to-book value. Growth stocks, on the other hand, were identified as companies whose earnings were expected to increase at an above average rate. These are often smaller companies.

In the 80’s and 90’s, a fund manager’s returns could be attributable to a combination of:

- market beta;

- the style of the portfolio eg value or growth; and

- alpha.

Value investing, in particular, had significant support during this time. Many value managers point to the work of Benjamin Graham, regarded by many to be the father of value investing to support their long-term approach. Graham’s student Warren Buffett and his investing partner, Charlie Munger, are strong advocates of this approach. According to the commentary in the introduction of the 2003 edition of Graham’s Intelligent Investor, at the time, prominent value advocate and active manager Peter Lynch had the best 20-year return of any mutual fund ever.

Investors were now recognising, beyond beta, performance was attributable to the manager’s skill and their style. Lynch’s portfolio benefitted from its exposure to value and the skill of the manager. The portion attributable to ‘alpha’, as illustrated by the diagram above, is getting smaller. Finding a manager with this skill was becoming more difficult.

Into the new century, more sophisticated research into the persistent drivers of stock returns saw the rise of identifiable ‘factors’ beyond value and growth as well as factor indifferent approaches such as equally weighting a portfolio. According to index provider MSCI, there are six main equity style factors: quality, size, value, momentum, dividend yield and volatility. You can read about these in more detail here: Vector Insights – Factors that can boost investment outcomes.

Technological advances and the dramatic increase in the availability of data or “big data”, as it is referred, has seen more active stock-pickers’ returns attributed to these factors.

The result is a further reduction in the part of the return attributed to the manager’s skill, or alpha. Active managers now need to be able to demonstrate that their individual skill is generating sufficient alpha, if they can at all, to justify their fees.

The rise of index-tracking passive investments such as ETFs have put further pressure on active managers.

New index design innovations that include factors, such as value, are now being tracked by passive ETFs and these ETFs have been delivering targeted outcomes while retaining the low costs of index investing. These ETFs are known as ‘smart beta’. Bloomberg’s Eric Balchanus described smart beta as “imagine R2D2 with the head of Peter Lynch”, it provides an important component of active management via simple, transparent, rules-based portfolios delivered at lower fees.

Smart beta has been identified as:

“a disruptive financial innovation with the potential to significantly affect the business of traditional active management.”

(Kahn and Lemmon, 2016)

One group of active fund managers that have been under pressure from smart beta ETFs has been the aforementioned ‘value’ managers. Many of these managers have been around for many years, however, the rise of passive management and recent poor performance has seen many investors consider their investments and their allocation.

In response, many of these managers ‘drifted’ from the style that had served them so well for so long1. Now so-called ‘value’ companies are making a comeback and many ‘active’ value funds are not capturing the ‘factor’.

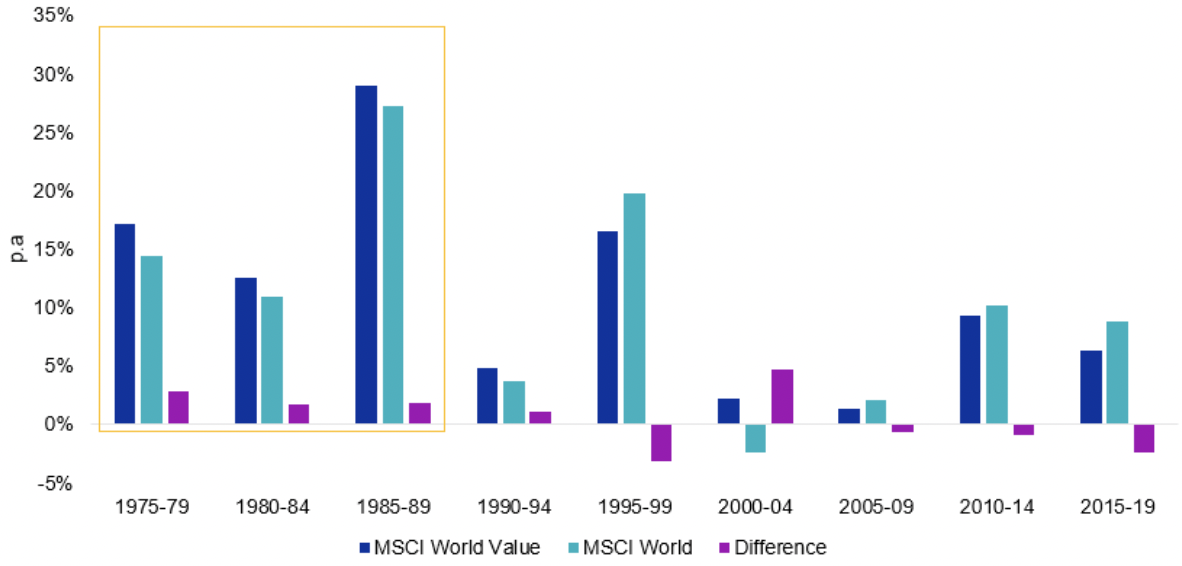

Historically, value companies have outperformed when inflation and interest rates increase, as they are less sensitive to changes in macro-economic conditions. High inflation and rising rates were characteristics of markets in the late 70s and 80s.

Five year per annum performance comparisons

Source: Bloomberg. MSCI, MSCI World Value index inception 31 December 1974. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Given the current economic environment in which inflation is high and rates are either rising, or expected to rise, value is making a comeback.

Using ETFs for value investing

Australian investors can now access entire portfolios of international securities selected on the basis of individual or multiple factors via a range of ETFs on ASX including the VanEck MSCI International Value ETF (ASX: VLUE). VLUE tracks MSCI World ex Australia Enhanced Value Top 250 Select Index.

MSCI’s Enhanced Value Index applies three valuation ratio descriptors on a sector relative basis:

- price-to-book value;

- price-to-forward earnings; and

- enterprise value-to-cash flow from operations.

Compared to a traditional value approach, MSCI’s enhanced value overcomes many of the criticisms of value because it puts less weight on price-to-book as a metric and moves away from backward-looking dividend yield altogether. It uses a whole-firm valuation measure in enterprise value that could reduce concentration in leveraged companies. It also employs a sector neutral approach that MSCI found mitigates some of the drawdown inherent with the value investing style.

Value investing has come a long way since the 1980s, but the underlying principles remain the same: identifying companies that appear under-priced using fundamental analysis.

We believe factor-based ETFs, such as VLUE, are ideal building blocks for an investment portfolio due to their:

- lower costs;

- ease of trading;

- explicit rules based methodology;

- transparency of holdings; and

- reduction of risks, including liquidity, key man risk and investment process risk.

For more information about how investors are using VLUE, click here

For more information about VLUE, click here.