2021 was a year where asset managers found it tough to exceed the market even though indices themselves notched up very strong gains. David Kostin, Goldman Sachs equity strategist, published his first Kickstart of the New Year in January 2022 highlighting the lack of alpha capture by fund managers. In fact, just 20% of core and 15% of growth-focused funds outperformed their benchmarks over the course of the year.1 We found the going tougher than usual too; it felt as if there were banana skins everywhere – whether it was the meme stock rush in Q1 that led to strong gains for the likes of Gamestop and AMC on a zero fundamental basis or the China meltdown that started in Q2 with the failure of Bill Hwang’s Archegos (his funds lost USD 20 billion+ in days before he was forced to close down) and extended into chaos as the Chinese authorities cracked down first on education and then a number of sectors rendering the former shares almost worthless.

Finally in Q4 the market saw a strong swing to value with, as a proxy, the S&P 500 Hardware sector returning a monster 23.8% versus the S&P 500 Software sector’s very modest 8.7%.1 The juxtaposition of sector moves quarter by quarter were hard to navigate, in our view. Atypically for us, we identified the swing to value well, spotting the real risk early on. There were plenty of areas to capture interesting growth themes without necessarily having to focus on high growth individual names. Within the Digital 4.0 theme that we identify as a potential opportunity over the next five to 10 years, there are clearly high growth, well known top performers like Nvidia, for example, as an enabler for data and AI – its shares rose 125% in 20211 – or Ambarella in autonomous driving whose shares rose 120%. But equally, the very same theme of big data can be expressed through owning storage names that carry significantly less risk. Seagate, as an optically boring hard disk drive manufacturer (HDD), rose 82% in 2021 based on many of the same drivers as higher risk Nvidia while ending the year at a rather modest 12x prospective earnings versus the rich 50x attached to Nvidia. Elsewhere, the connectivity of everything drove opportunity in industrials, healthcare and transportation. We always look to identify the right theme and then express that with the best balance of risk and benefit, not necessarily in the highest profile or well-known names.

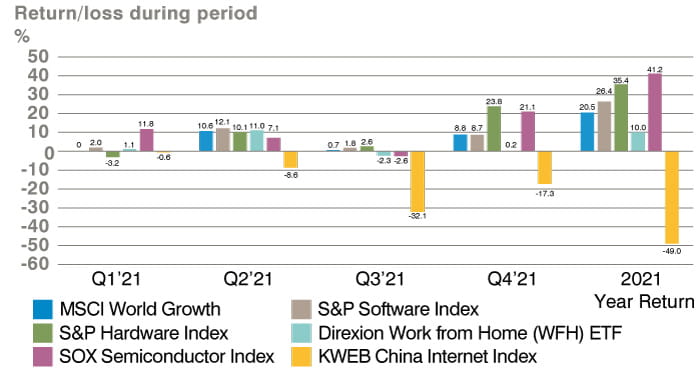

China was a difficult market for disruptive investing in 2021 and added yet another strand to a complex picture of inter-sector performance. Chart 1 below lays out the key factor drivers as we saw them for the year and shows quarterly shifts.

Chart 1: Index performance in 2021

China, particularly as defined by the KWEB US listed Internet names, stands clear as a significant underperformer in 2021. A 50% fall over the course of the year was caused first by the Archegos collapse and then the Chinese regulation of the education sector requiring it to become not-for-profit – that led to shares in the sub-sector falling over 90%.1 This was quickly followed by regulator concerns over consumer data and a very public spat between the Chinese authorities and Didi that led to a further wave of sell-offs. Finally, the seemingly inexorable requirement for Chinese companies to seek the relative safety of a Hong Kong listing drove an additional wave of selling as investors, unable to switch from US ADRs to HK listed shares, ran for cover. Chinese A-Shares in sectors actively supported by the government fared far better with electric vehicles (EV) and renewables names in particular making strong progress.

The S&P 500’s 29% 2021 gain1 was a tough bogey for many companies and certainly for asset managers. FAANG had plenty of diversification in returns with Apple and Google beating the S&P and Meta (formerly Facebook), Amazon and Netflix underperforming. While not FAANG names, Tesla and Microsoft should be included in the mega-cap list. They both outperformed well, up around 50%.1 The dispersion is a worrying sign in some ways; during the final week of 2021, Bloomberg reported that as the S&P 500 made yet another all-time high, 334 companies trading on the New York Stock Exchange were making 52-week highs while twice that number were making 52-week lows – the last time that happened was just before the 2000 crash. In addition, the Wall Street Journal reported that the average PE of the top 10 names in the S&P by value were trading at a 68% premium to the 25-year average, a period that includes the 2000 dotcom bubble. Clearly there are cautionary signs in the market and that, we believe, has led to some air being very firmly squeezed out of some over-hyped parts of the market. The ARK ETF highlights this as well as anything, with a 23% decline on the year and an almost 40% drop from the early year highs.1 Cathie Wood, CEO of Ark Invest, commented that she had never seen her portfolio down in an up year for the market and cites a 40% compound return expectation following the fall. A strong performer over the years for ARK has been Tesla; it continued its meteoric rise following a 750% gain in 2020. Valuation here still dumbfounds us – the market capitalisation of just over USD 1 trillion equates to about USD 1 million per car produced at the current run rate. Comparisons have been made endlessly, but as a reminder, Toyota as the world’s largest car manufacturer (by number of vehicles produced in 2021) produces 10 times the number of cars annually or about 10 million and has a market cap per car of just USD 31,000.

Among other large-cap names, the underperformance of Amazon stood out with a rise on the year of just 2.4%1, which reflects a fading of WFH (work from home) names. The chart above shows that the WFH ETF rose just 10% in 2021. There are many names that lost a great deal of ground led by Zoom, down 44%.1 Other WFH favourites also fared badly – the worst performing name in the S&P Internet Select Industry index was Contextlogic (-77%)1, a plain vanilla e-commerce company. We have believed for some time that non-differentiated e-commerce would likely struggle – in 2021 their star finally fell. While Wayfair for example was down just 12% on the year, it fell from a high of USD 369 to just USD 190 at year end (-49%).1 In Europe, losses were more substantial on the year overall – Allegro (the Polish Amazon) -54%, Home 24 -48%, Asos -42%, Boohoo -42%.1 Food delivery, driven by the same WFH boom, fell back too.

The other major trend that drew our attention during the course of the year was the interplay between growth and value. While not as obvious as in previous cycles, like the 2015/16 rotation, there was a clear tendency towards the safety of profitable cash generative businesses with a growth bias, often known as GARP (growth at a reasonable price). This led the market, looking for innovation, to alight on semiconductors, a sector seemingly offering all of the above. We believe that whatever the growth outcome for 2022 and beyond, the valuation attached to semiconductors is now such that the growth / value risk has likely been sharply reduced.

Finally, in summing up the year and the way in which the market has become more sanguine, the IPOX SPAC index reached an all-time high in February 2021 having rallied almost 100% from the October 2020 lows. It then proceeded to fall 34% through to the end of the year.1 This hides the true fate of many names that did far worse. While a SPAC waiting for a deSPAC deal might tend to trade around its issue price of USD 10 and thus hold the index up, there are many cases where deSPACs have gone very wrong, in our view. Add together a further need for cash to fund losses in target companies that themselves miss the aggressive (unregulated) forecasts given out at the time of the deSPAC merger and in the market of 2021, investors have exited first and asked questions later. Many of them were invested for the SPAC protection and not the merger opportunity that only further added pressure to prices.

One sub sector of note to act as an example of this is digital health, one of the earlier battlegrounds for SPACs looking for deals. The failures have been spectacular. Talkspace in ‘behavioural healthcare’ was down 82% in 2021 to just USD 2.1 a share1; Owlet, which monitors heart patterns via an app, closed the year at USD 2.71; UpHealth, described as a ‘patient centric digital health platform’, ended at USD 3.91, and Beachbody, a Peloton-type clone, closed at USD 2.5.1 All these companies would have started their lives at the base SPAC price of USD 10. In our view, there have been some positives – IonQ trades at USD 171 as possibly the only pure play quantum computing company on the market. The SPAC market as it matures is likely to throw up some interesting opportunities from the embers of the 2021 demise. Quality operating businesses are starting to use the SPAC route to market, like Cvent in event management or Airspan in OpenRAN software for next generation high speed mobile networks, for example. Like many new business types, SPACs are following the tried and tested Gartner Hype Cycle. We are currently in the trough of disillusionment as 2021 has proved to be a watershed year for differentiating winners and losers.

We believe that the 2021 back to reality grounding effect could likely set a much more attractive backdrop for active managers in 2022.

Click HERE to download the Disruptive Strategist Q4 2021.