Introduction

The last few days have seen a sharp escalation in the situation between Russia and Ukraine, with Russia recognising the independence of two regions in the Donbas area of eastern Ukraine that have been controlled by Russian separatists since 2014 and ordering Russian “peacekeeping” troops into the regions. At this stage its unclear how big the force will be, whether it will push beyond the areas controlled by the separatists and, if so, how far. Although President Putin continues to deny plans to invade Ukraine, his comments suggest a move into the areas of Donetsk and Luhansk in the Donbas that the rebels do not yet control.

As a result share markets have fallen further, with US and global shares falling just below their January lows and Australian shares under pressure too, albeit so far they have held up a bit better. Bond yields have also fallen due to safe haven demand and oil prices have pushed to new post 2014 highs. The market reaction reflects a combination of uncertainty around how far the conflict will go – with Ukraine being Europe’s second biggest country (after Russia), the threat of further sanctions (so far they have been limited) and uncertainty about how severe their economic impact will be. Although it has said it won’t, there is also the risk Russia cuts off its supply of gas to Europe where prices are already very high, with a potential flow on to oil demand at a time when conflict may threaten supply. In short, investors are worried about a stagflationary shock to Europe and, to a lesser degree, the global economy generally.

Possible scenarios

Trying to work out which way this goes is not easy and I am not a geopolitical expert. But it still seems there are four scenarios, some of which may overlap:

- Russia stands down – this would provide a brief boost for share markets, including Australian shares, (eg +2 to +4%) as markets reverse recent falls that were driven by escalating tensions.

- Russia moves in to occupy the Donbas areas that are already controlled by Russian separatists with sanctions from the west but not so onerous that Russia cuts of gas to Europe – this could see a further hit to markets (say -2%), although it looks like it may be getting close to priced in. This may be similar to what happened in the 2014 Ukraine crisis (with Crimea) and if that’s all that happens then markets would soon forget about it and move on to other things. Much as occurred in 2014.

- Russian invasion of all of Ukraine with significant sanctions and Russia stopping gas to Europe but no NATO military involvement – this would cause a stagflationary shock to Europe & to a less degree globally as oil prices rise further and could see a bigger hit to markets (say -10%) but then recovery over six months.

- Invasion of all of Ukraine with significant sanctions, gas supplies cut & NATO military involvement – this could be a large negative for markets (say -15-20%) as war in Europe, albeit on its edge, fully reverses the “peace dividend” that flowed from the end of the cold war in the 1990s. Markets may then take longer to recover, say 6-12 months.

Given the path Russia has gone down and the stridency of President Putin’s recent comments, Scenario 1 is looking less and less likely, but is still possible if there is a breakthrough in talks. And Scenario 2 looks to be already on the way, with Putin’s ordering of “peacekeeping” troops into the Donbas region. This may be the “military-technical” action that Russia referred to last week. At the other extreme, it’s still hard to see Russia undertaking a full invasion of Ukraine given the huge cost it would incur. And it’s hard to see NATO troops being involved particularly given limited public support for it in Europe and the US. The US has said US forces would not go into Ukraine. However, some combination of scenarios 2 and 3 are possible whereby the crisis escalates further if, say, the Donbas separatists and the Russian “peacekeepers” push into Donbas territory that the separatists do not yet control and beyond.

And, of course, with Russian troops moving into the Donbas region of Ukraine investment markets will worry that we will move on to a wider invasion of Ukraine, until signs appear to the contrary. So, we could still see share markets fall further and oil prices rise further in the short term.

Crisis and share markets

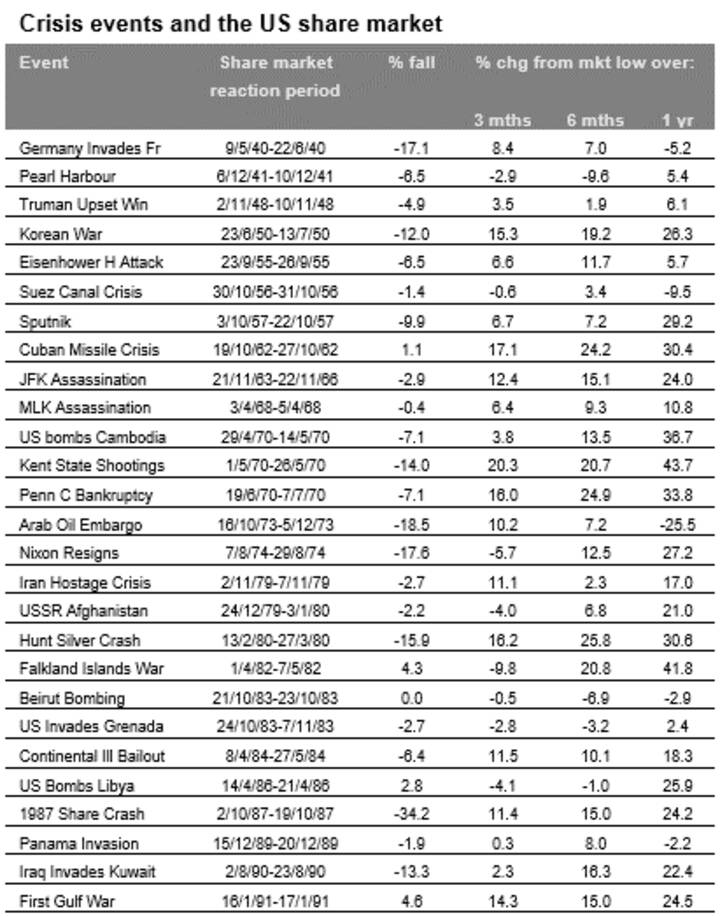

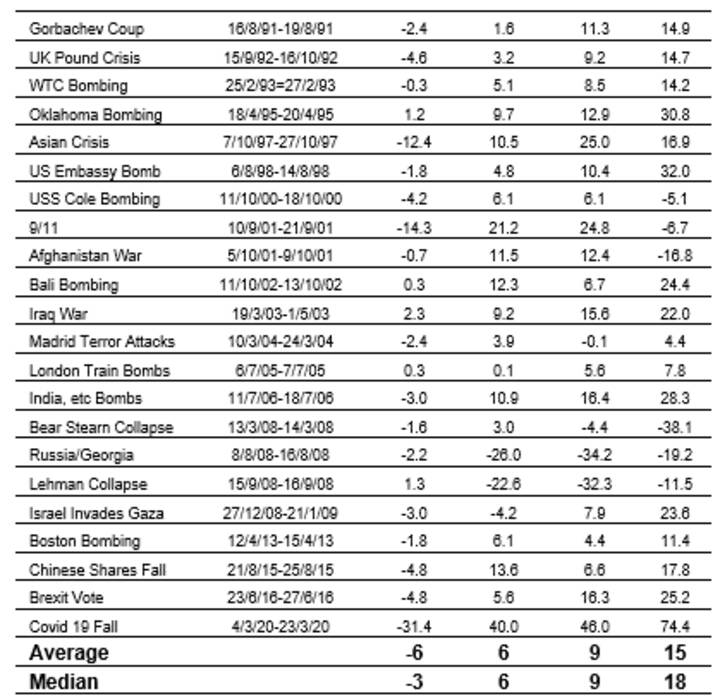

Of course, there is a long history of various crisis events impacting share markets. This includes major events in wars, terrorist attacks, financial crisis, etc. The following table shows major crisis events since World War Two in the first column, the period over which the US share market initially reacts in the second column, the percentage share market fall in the third column and the percentage change from the low over 3, 6 and 12 months in the final three columns.

Based on the Dow Jones Index. Intended as a guide only as other developments also impact shares around the dates shown. Source: Ned Davis Research

The pattern is pretty much the same for most events, with an initial sharp fall in the share market followed by a rebound. Since World War Two the average decline has been 6%, but six months later the share market is up 9% on average and 1 year later its up around 15%.

What does it all mean for investors?

I don’t have a perfect crystal ball and its even hazier when it comes to events around wars. But from the point of sensible long-term investing, the following points are always worth bearing in mind in times of investment markets uncertainty like the present:

- Periodic sharp falls in share markets are healthy and normal, but with the long-term rising trend ultimately resuming and shares providing higher long term returns than other more stable assets.

- Selling shares or switching to a more conservative investment strategy after a major fall just locks in a loss and trying to time the rebound is very hard such that many only get back in after the market has recovered.

- When shares fall, they are cheaper and offer higher long-term return prospects. So, the key is to look for opportunities the pullback provides. It’s impossible to time the bottom but one way to do it is to average in over time.

- While shares have fallen, dividends from the market haven’t. Companies like to smooth their dividends over time – they never go up as much as earnings in the good times and so rarely fall as much in the bad times. And in the meantime, the income the dividends provide is still being received.

- Shares and other related assets bottom at the point of maximum bearishness, ie, just when you feel most negative towards them.

- The best way to stick to an appropriate long-term investment strategy, let alone see the opportunities that are thrown up in rough times, is to turn down the noise around the news and opinion flow that is now bombarding us.