Introduction

Humans do horrible things to each other, and war is the worst example of that. What was first announced by Russia earlier last week as a “peacekeeping” force moving into part of eastern Ukraine controlled by Russian separatists quickly morphed into a full-blown attack. This in turn has seen a progressive ramping up in western sanctions on Russia. All of which has contributed to high levels of financial market volatility. This note looks at the current situation, five big picture implications of relevance to investors and the performance of Australian shares.

The current situation

The falls and volatility in global share markets in response to the war reflects a fear of the unknown about how far the conflict will extend and how severe the economic impact will be. The main economic threat is through higher energy prices as Russia supplies around 30% of Europe’s gas and oil imports and accounts for around 11% of world oil production. In short, investors are worried about a stagflationary shock.

If the conflict is limited to Ukraine with Russian gas still flowing to Europe and NATO not getting directly involved (Scenario 1), then the economic fallout will be limited, and further share market falls may be minor or we may have seen the low. But if Russian energy is cut off and NATO military forces get directly involved (Scenario 2) then share markets could have a lot more downside (like another 15% or so). And given the uncertainty investors may fear the latter scenario even if its ultimately avoided. There are several points to make regarding all of this.

- First, Russia is aiming to prevent Ukraine joining NATO but it has no interest in war with NATO as Russian military capability is weaker. President Biden has continued to stress that the US will not engage in military conflict with Russia – just as it managed to avoid it through the Cold War. The presence of nuclear weapons on both sides remains a huge deterrent – as President Putin reminded us. This along with western sanctions excluding Russian energy exports should help limit the war to Ukraine and minimise the global economic impact. This would favour Scenario 1.

- But trying to get geopolitical moves right is never easy. And there is a high risk the situation gets worse before it gets better. Things may not be going as well as Putin first assumed. Ukrainians seem to be fighting back hard. The West seems to be a lot more united and strident in its response to Russia including via severe sanctions (which will drive deep recession in Russia) & the supply of military equipment to Ukraine. Even China failed to support Russia at the UN & has expressed concern about harm to civilians.

- While a backdown by Putin is possible, to avoid a humiliating outcome he may go in harder. But with images being beamed around the world a more forceful Russian attempt to gain control with huge loss of life could further harden global resolve against Russia.

- European exports to Russia are just 0.7% of its GDP and US exports to Russia and Ukraine are less than 0.2% of its GDP so the direct impact on them from a collapse in the Russian economy would be small. The main threat comes via a hit to energy supply and so far the US and Europe have sought to minimise this threat by excluding the Russian energy sector from the sanctions.

- The US economy is far less vulnerable on the energy front than Europe as it produces and exports more energy than it consumes and imports. Russia needs the revenue from its energy exports to Europe and it’s not possible for it to quickly replace exports to Europe with exports to China (as the gas pipeline is already at capacity). But the more the sanctions on Russia escalate and the conflict goes on the greater the risk that Russia will curtail energy supplies. This is why the oil price has surged to around $US115/barrel.

- Even if there is no direct disruption, energy prices are likely to be higher than otherwise reflecting a risk premium as long as uncertainty remains high around supply. The same will apply to other commodity prices including foodstuffs where Russia and Ukraine are significant producers – eg, they account for about 25% of global wheat production.

No one knows for sure how this will unfold. But as we pointed out last week there is a long history of various crisis impacting share markets and the pattern is the same – an initial sharp fall followed by a rebound. Dark as it may seem at present the same is likely to apply this time as well, but trying to time it will be hard, so the best approach is for investors to stick to an appropriate long-term investment strategy. There are some things that will help drive a rebound once some dust settles:

- Just as in the Cold War (when the ideological divide was wide) Russia & the West will likely find a way to co-exist.

- The crisis is more inflationary than deflationary, but for the next few months its likely to be a constraint on more rapid central bank rate hikes.

- Additional defence spending will provide a boost to growth.

- While European growth will take a bit of a dent, global growth this year is still likely to be strong at around 4%.

- As a result, company profit growth is likely to remain solid this year, albeit down from last year.

Five big picture implications of the Ukraine crisis

On a medium-term basis though, the war in Ukraine will have some lasting implications of relevance to investors.

#1 A new “cold war” & reversal of the peace dividend

Geopolitical tensions were on the rise prior to the pandemic with the relative decline of the US & faith in liberal democracies waning from the time of the GFC. This has seen various regional powers flex their muscles – China, Russia, Iran and Saudi Arabia. The pandemic inflamed US/China tensions. And now Russia, under President Putin, is seeking to stop the eastward drift of NATO using force and to restore Russia to some of its former status, against the background of a Russia-China partnership. All of which is leading to fears (or maybe the reality) of a new cold war which the Ukraine war has given a push along. This in turn means a return to ramping up defence spending (with even Germany now planning to increase military spending to 2% of GDP) – reversing the peace dividend that saw countries reduce defence spending and allocate public spending to more productive uses in the post-Cold War era.

Implications: it may be good news for defence stocks but heightened geopolitical risks adds to investment market volatility and may require higher risk premiums (ie, lower price to earnings multiples) on growth assets. But its not all negative as the competition between nations can boost technological innovation as it did in the post WW2 Cold War.

#2 Reduced globalisation

A backlash against globalisation became evident last decade in the rise of Trump, Brexit & populist leaders. Coronavirus added to this with pressure to onshore supply chains. A reversal in globalisation has been evident in recent years in a peak in global exports and imports as a share of global GDP. Short of a quick negotiated solution or Putin being replaced there is a high-risk Russia will be excluded from much trade with the West for years, driving a further reversal of globalisation. Higher war risks also add to pressure for onshoring.

Implications: reduced globalisation risks leading to reduced growth potential for the emerging world generally, reduced global competition and reduced productivity if supply chains are managed on other than economic grounds. It threatens to add to inflationary pressure in the global economy. It will also reduce the breadth of global share and bond indices with Russia likely to be removed from global equity and bond indices – albeit its only 0.3% of the global share index.

#3 Higher commodity prices

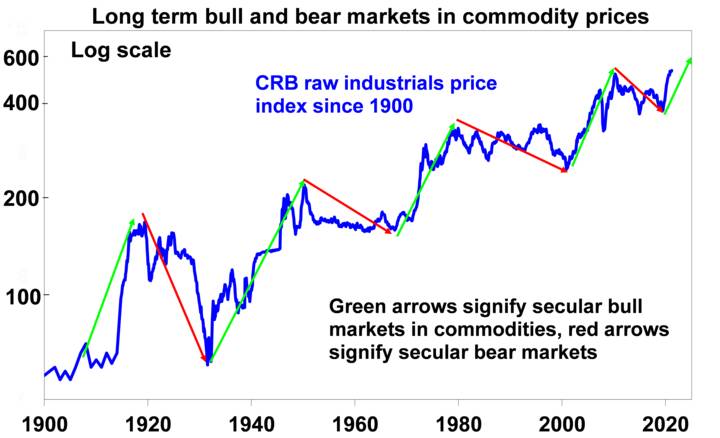

The Ukraine conflict, thanks to the disruption and threats to the supply of energy, industrial and agricultural commodities and increased demand for metal intensive defence goods is providing a further boost to commodity prices and adds to the case that we have entered a new commodity super cycle. This is also underpinned by low levels of resource investment in recent years and decarbonisation.

Source: CRB, Bloomberg, AMP

Implications: this is good news for commodity producers like Australia, but bad news for commodity importers like most industrial countries. It may see Australian shares and the $A outperform like during the commodity boom of the 2000s.

#4 Higher inflation

The boost to commodity prices – notably for energy and food – from the Ukraine war and longer-term from increased defence spending and a reversal in globalisation will further add to global inflation pressures. While the boost to energy and food prices may be temporary, the danger is that coming on the top of already high inflation rates it will add to inflation expectations and become more entrenched.

#5 Higher interest rates

The near-term uncertainty caused by the Ukraine crisis may take the edge of central bank monetary tightening in the short-term. But ultimately the hit to economic activity globally and in Australia is likely to be limited and the upwards pressure it adds to commodity prices and the risk of higher inflation for longer will reinforce the case for monetary tightening, and see higher interest rates and bond yields over the medium-term.

Implications: higher inflation, interest rates and bond yields will constrain longer-term returns from shares and property compared to what we have seen over the last 30 years.

Why are Australian shares holding up a bit better?

From their bull market highs global shares are down 8%, but Australian shares are only down 6% and have so far held above their January low. Australia will suffer from any hit to global growth from the crisis and Australian consumers will be hit with record petrol prices which could easily spike another 15-20 cents a litre in the next few weeks reflecting the rise in global oil prices to around $US115 a barrel. Against this though, Australia is relatively well protected: our trade links with Russia are trivial – with exports to Russia accounting for less than 0.1% of GDP; many of our energy and agricultural products can help fill the global gap left by disruption of Russian and Ukraine exports; and national income will receive a boost from higher energy and commodity prices. And finally, the just ended profit reporting season was positive and (based on calculations by The Coppo Report) will see $36bn in dividends paid to investors over the next two months, which is nearly 40% up on a year ago & only just down on the record payments six months ago. All of which should help the relative performance of Australian shares.