by Julian Howard – Lead Investment Director, Multi-Asset Solutions

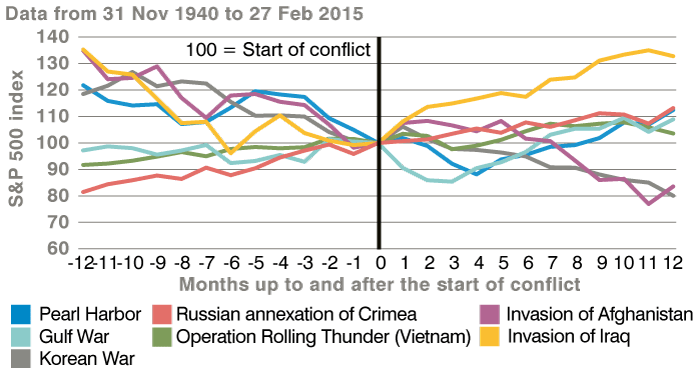

In March 2003, Saddam Hussein’s Information Minister Saeed al-Sahaf became world famous for predicting US defeat even as tanks rolled and bombs rained down behind him. ‘Baghdad Bob’, as he came to be known, added to investors’ impression of a certain US victory over an inept foe, and equity markets rallied accordingly. This was no mere blip either. The S&P 500 had fallen 44% from its technology boom peak in March 2001 up to this point but the invasion kickstarted a longer rally which was to endure right up until the global financial crisis of 2008. For many, this provides a reassuring example of how the mere removal of uncertainty can set jittery markets right again (see chart below). What then to make of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022? While a Russian tactical victory may seem likely – though not as much as at the start of hostilities – we believe the broader implications for markets and the global economy will be more profound than in 2003.

War has not been universally bad for markets:

The sanguine case for a relief rally based on the end of uncertainty has some merit. Even on the day of Russia’s invasion, the Nasdaq ended the day up 3.4% as reports came through that Russian units were closing in on the Ukranian capital Kyiv. In this sense, this latest war is seemingly following the Iraq playbook. But the similarities may also persist in uncomfortable ways. Ukraine is relatively well armed and determined, and the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS) has suggested that Russia’s advantages may fade in the context of an urban conflict. A prolonged insurgency raging on Europe’s doorstep may sustain investor nervousness, along with the sanctions the West is piling on to a country with relatively deep capital markets.

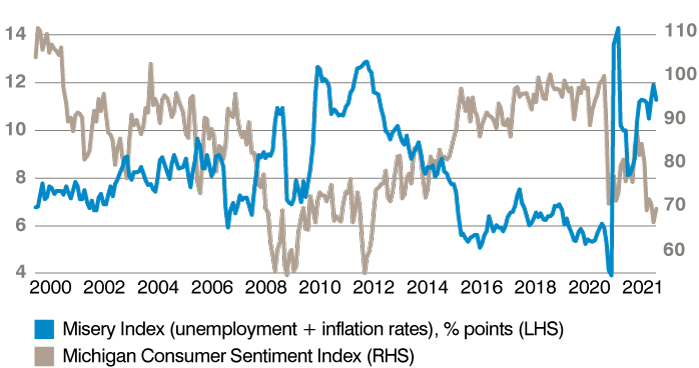

More palpable will be the inflationary impact of the invasion and its aftermath. Oil and gas prices have been soaring as concerns about supplies mount given Russia’s status as a major producer that supplies nearly half of Europe’s natural gas, some of it via pipelines through Ukraine itself. The effect on consumers is likely to be significant. This matters especially because of the effect on the real economy. Unemployment and inflation together have been used by economists to construct a US ‘Misery Index’ which correlates inversely with consumer sentiment and has profound implications for the likely course of economic growth. While unemployment is relatively low today, headline inflation is running at 7.5%, as at the latest January print according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, sharply pushing up aggregate hardship for consumers even though employment itself is plentiful.

Have a job, but can’t afford much:

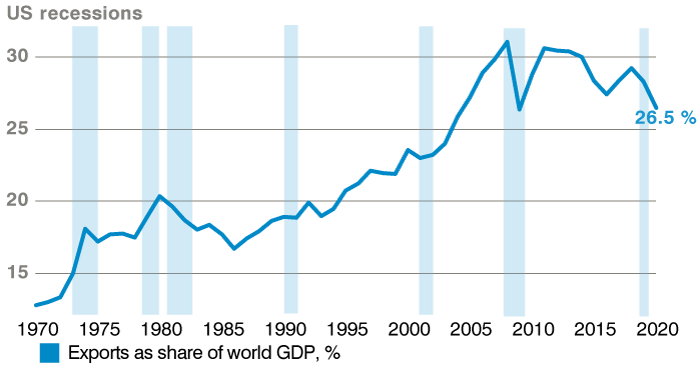

A longer-term growth-negative outcome from the invasion of Ukraine is deglobalisation and the accelerated decline of world trade. It is only likely to suffer more as Russia retreats from the world economy under the weight of the aforementioned Western sanctions and an associated desire for energy dependent economies to reduce reliance on Russia’s natural resources. Indeed, the invasion of Ukraine only serves to highlight a wider geopolitical fracturing – a ‘new cold war’ – that has become more apparent over the last decade. We believe that China’s initial failure to outrightly condemn Russia’s invasion and instead only call for “restraint” is no coincidence given its own rhetoric around Taiwan’s status. Just as Western developed economies will now likely seek to disentangle themselves from Russia, we expect them to also seek independence from China amid concerns over human rights abuses and the supply chain disruptions brought about by (politically motivated as some see it) zero-Covid policies. This inward turn will likely take years if not decades to complete but we believe the invasion of Ukraine has confirmed in many policymakers’ minds the pressing need to ‘deglobalise’.

New cold war likely to send world trade into retreat:

We expect the consequences of the invasion to impact global economic growth both in the short term and long term. If there is any silver lining to be had from this grim prospect it is that the heightened economic uncertainty may well prompt the US Federal Reserve (Fed), the Bank of England and to a lesser extend the European Central Bank to reassess the need to aggressively raise interest rates.

With a CBS/YouGov survey in February revealing that 58% of voters feel President Biden is not focusing enough on the economy, the pressure on the Fed to reprioritise growth over inflation will likely be mounting. What has become painfully apparent is that the central bank’s main policy tool – interest rates – is powerless to fix supply shocks without inflicting further damage on an economy that could soon be flirting with recession. As such, we sense the Ukraine invasion could deter the major central banks from their recently expressed desire to raise interest rates. Meanwhile, long-term rates, which have already sunk to below 1.9% per the 10-year US Treasury yield, as at 8 March 2022, may fall further in the medium term to reflect the lower growth described. This could ironically restore the underpinnings of asset prices after the volatility seen so far this year, in our view.

We believe the restoration of a low growth, low interest rate environment would likely result in renewed support for long duration assets such as government bonds and growth-style equities including technology. Investors may yearn for the relative simplicity of the US invasion of Iraq nearly 20 years ago, but the profound implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – tragic as it is on a humanitarian level – may yet assist in unexpected ways.