The last dozen years has shown that the US downstream petroleum industry has adjusted and mostly thrived in response to major structural changes. Can it now meet the new missing million-barrel refining gap?

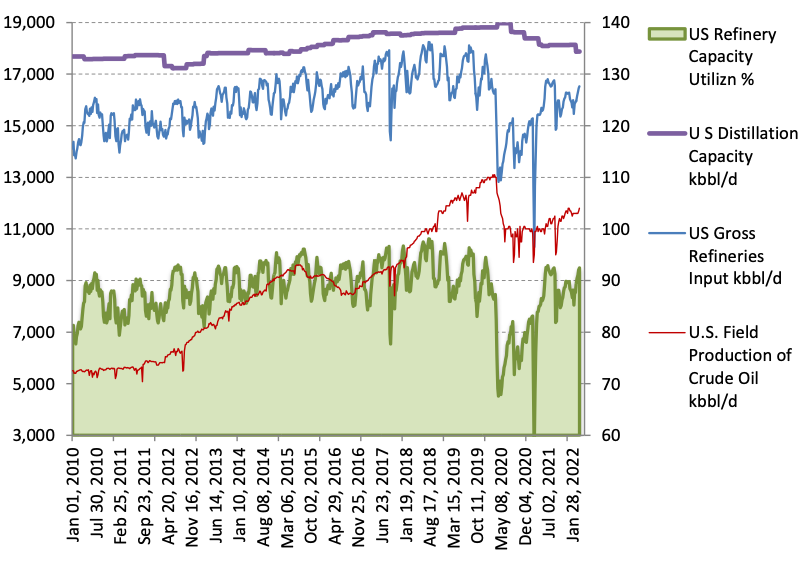

Early in 2020 the US recorded twin peaks of oil production at 13.1 million barrels/day (mb/d) and refining distillation capacity of 19.0 mb/d and with a healthy capacity utilisation of ~92%. This culminated the US petroleum industry’s incredible transformation which in 2010, US crude oil production was just 5.5 million bbl/day (mb/d) and the US refining sector was distilling around 15 mb/d of inputs with capacity utilisation under 85%.

US Crude oil production and refinery throughput and capacity in ‘000 b/d

Source: US EIA

In the decade prior to 2020, the US refining industries’ keen focus shifted from import logistics to capacity management. Twin tailwinds of rising local crude production and gradually rising products consumption saw renewed investment in modern plant. Profit margins and refining capacity utilised trended up. The US’s competitive cost position enabled to export ~2.9 mb/d of refined products or nearly 3% of world products supply.

As 2020 progressed, the Covid-19 pandemic led to sharp consumption fall, excess inventories, and a collapse of both the oil price and petroleum product margins.

Since 2020, US refiners shed 1.1 mb/d of refining capacity, in a rationalisation process that is still underway.

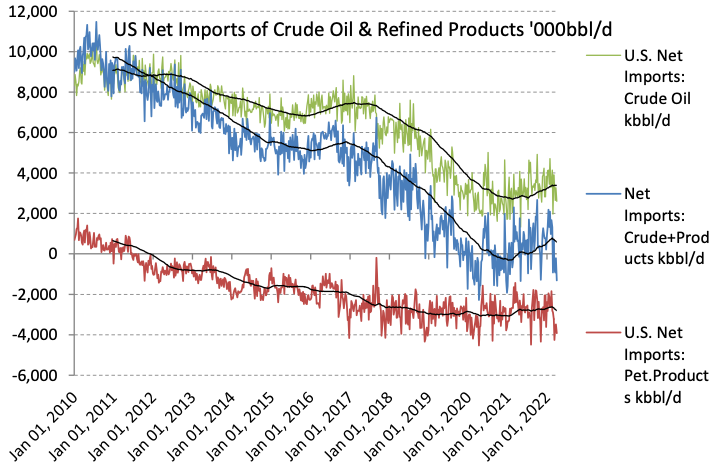

Since 2020 US crude oil net imports (green) have been trending up; while US net product exports(red) have flat-lined

Normalising US demand = reducing product export capacity for the rest-of-the-World

US diesel, gasoline, fuel oil and now aviation kerosene demands are normalising towards pre-pandemic levels. US refining capacity utilisation has recovered to 92.5% which is close to the sustainable maximum utilisation due to refining plant maintenance requirements.

Further demand growth is expected particularly in aviation and diesel fuels as travel and industry fully recovers. Without new investment in refining capacity, the impact may be see US refined product exports shrink, at exactly the wrong time in a World with added geo-political supply chain challenges.

Similarly, US crude oil production remains at 1.3 mb/d below its 2020 peak. Crude output also needs to expand around 1.0 mb/d if the US is to first stabilise and then slightly pare back its net crude imports.

Differing incentives to re-invest – refining has a problem

Investing in new oilfields is recovering slowly with crude rising 0.3 mb/d since Jan 2022 to 11.8 mb/d, a trend we think could persist but only gradually.

Why? It takes a redoubled drilling and well completion effort to replace rapid-depletion shale oil fields and then add extra capacity.

High oil prices assist with free cashflows to re-invest in shale oil fields. This is not a hard decision to make when shale oil well paybacks are measured in a few quarters. However, we count Government efforts to depress oil prices by Strategic Stocks release as a counter-productive signal.

The greater problem is re-investment in US refining capacity as paybacks are measured in 5 to 10-year periods. These timeframes overlap with the potential for peaking petroleum fuels consumption due to Electric Vehicles. Along with narrowing funding sources for fossil-fuel investments and shareholder pressure to maintain payouts versus growth, it all adds up to a problem. There is a potential 1.0 mb/d and growing refining gap opening up in the US over the next few years.

The refined products shortfall would likely be resolved in lower exports of US petroleum products to the rest-of-the-World.

Inadequate energy investment = adding to risks of stagflation

Inadequate investment, even in the face of strong oil and products price signals can lead to structurally higher price indices.

Oil and petroleum products are vital inputs that have a pervasive cost-push impact across wide sections of agriculture, industry and transport. Ultimately this is paid for by households who will seek then seek higher wages.

The more consumers’ money is spent on energy means less money available for other goods and services. GDP growth can slow and yet still see elevated price inflation linger.

Globally, economies are struggling with bloated fiscal deficits, rising interest rates and trade flow interruptions. This means the World is far less resilient to further shocks. High energy prices may be the ingredient to increase risk of global slowdown or recession that curtails consumption of services and goods including energy. That is the painful way to resolve under-investment in a vital industry such as petroleum.

What happens in the US, matters in Asia

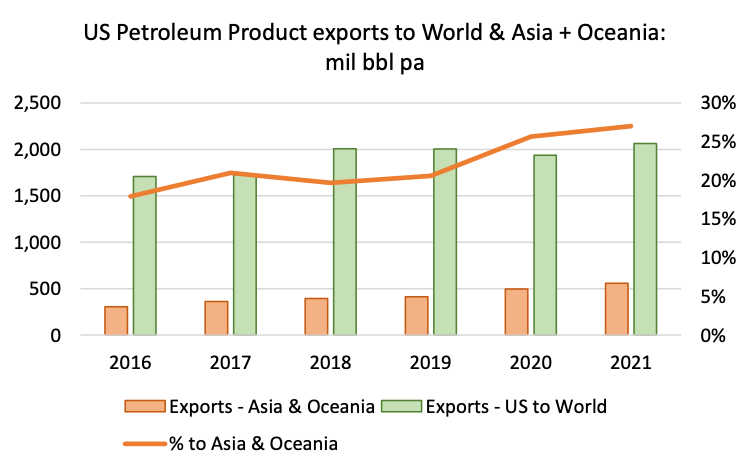

US refining industry exports have stabilised at around 2.0 billion bbls pa, though with Asia rising in importance from <20% in 2016 to 27% last year.

Should US refined products exports fall as US petroleum demand increases, the impacts can spill into the Asia-Pacific refined product markets and assist refining margins to remain elevated.

Locally, Ampol Ltd (ALD) and Viva Energy Ltd (VEA) would benefit from the persistence of good regional fuel margins. Though you would expect some volume offsets as consumers economise use of expensive fuel, the recent halving of the Federal Government’s fuel excise partially negates this market signal. This can assist the refiners to maintain sales volumes and margins, but at a cost to the Commonwealth’s treasury.

Tighter regional products markets mean that those groups with logistics and storage capabilities, as well as local refining capabilities would tend to capture enhanced profit margins. Refiners in Asia will however be looking to security of supply and to secure quality crudes to improve petroleum products yield. We see Australian hi-quality crude and condensate exports maintaining or expanding oil price premiums in Asian markets with Santos (STO), Beach Energy (BPT) and Woodside Petroleum (WPL) as beneficiaries.