by Joe Foster – Portfolio Manager / Strategist

Central banks are tightening, the global commodities shock is intensifying and over the first few days of April the spread between the US 2-year and 10-year treasury yields turned negative. Historically, these have been harbingers of a slowing economy or recession. Traditional safe havens gold and the US dollar trended higher in early April. Gold tested the US$2,000 per ounce level with an intraday high of US$1,998 on April 18. While the US dollar index (DXY) went on to test its 20-year highs, the gold market pulled back when, on April 21, US Federal Reserve Bank (Fed) Chair Jerome Powell sent a strong message at an International Monetary Fund (IMF) gathering. There he indicated that more aggressive hikes in interest rates are needed, presumably to fight inflation. Gold was also caught up in a broader commodities selloff when, on April 25, news of China’s worsening COVID outbreak threatened to weaken demand for basic materials. We believe the selling pressure on gold was misplaced, as gold has different drivers than other commodities. Chinese gold demand has returned to pre-COVID levels and the volatility and declines in the Chinese stock and real estate markets have sparked investment demand for gold.

Lingering COVID, rising costs

For the month of April, gold declined US$40.51 (2.1%) to US$1,896.93. The NYSE Gold Miners Index fell 8.18%. A number of companies have reported first quarter results that, so far, have been below expectations. Aside from nagging operating issues that crop up for all mining companies, it became apparent there are two primary reasons for the misses, COVID and cost inflation, and these may persist in the longer term. Canada and Australia are the regions hit hardest by temporary slow-downs or shut downs due to COVID. Remote operations with on-site camps are most vulnerable to outbreaks. Vaccinations have not become the cure-all as hoped, so it looks like miners will have to deal with COVID problems until the eradication of the virus.

Gold companies have been controlling costs by adopting new technologies and mine practices. Examples include autonomous haulage, replacing diesel with battery electric haul vehicles, using renewable energy and implementing new communication and data processing systems. However, with first quarter results, it has become apparent that the inflation that has been plaguing many companies and consumers is beginning to affect gold miners too.

Scotiabank’s tally of the larger producers shows that, on average, 45% of cash costs are attributable to labor, 8% to fuel, 6% to power, 21% to consumables and 20% to other miscellaneous costs. Costs have been increasing in all of these categories to varying degrees, depending on where a mine is located, how much fuel costs have been hedged and how much inventory is on site. We are expecting a 7% rise in all-in-sustaining-costs to US$1,150 per ounce, on average, in 2022. If the inflation we are seeing in the first quarter persists, many companies will have to increase their cost guidance later in the year. With gold in a bull market hovering around US$1,900, we believe that even with inflation, the industry’s robust margins are safe and gold stocks remain attractive.

Inflation rears its ugly head

In the seventies, a wage-price spiral fueled inflation for years. It now looks as if a new wage-price spiral has begun. The March US Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 8.5% and the Producer Price Index (PPI) surged 11.2%, the most on record. Meanwhile employment costs also jumped by the most on record, as the employment cost index gained 1.4% in the first quarter. Wide-ranging anecdotal evidence for long-term inflation continues to mount. According to April Wall Street Journal articles:

- Conagra’s CEO expects inflation 26% higher than two years earlier, due to higher meat and dairy prices, driver and truck shortages, fuel prices and continuing labor shortages

- West Texas drillers are facing long delays for everything from roughnecks to steel to fracking pumps

- Intel Corp.’s CEO said the chip shortage will last longer than expected

- Railroads attribute service problems to worker shortages and high demand

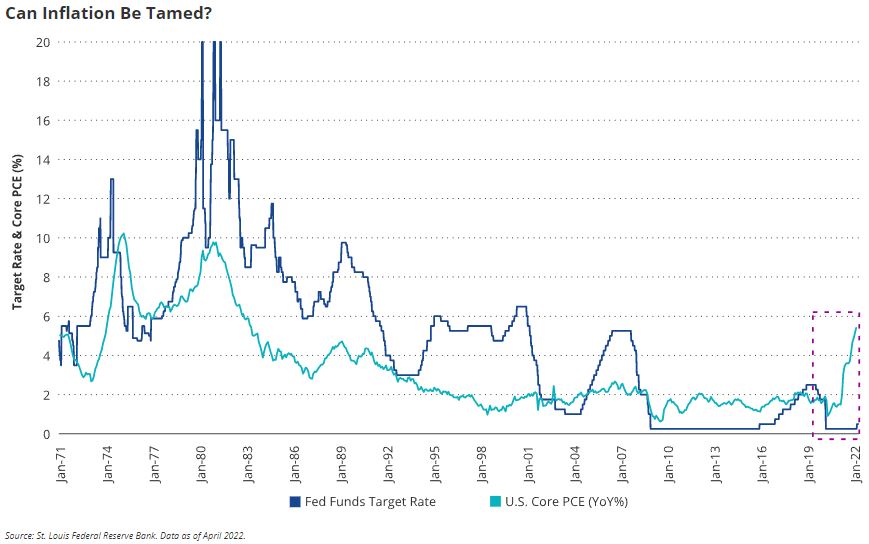

The Fed’s preferred inflation measure is the Core Personal Consumption Expenditures Index (PCE), for which it carries a long-term target of 2%. The chart below shows how far behind the Fed is in its inflation fight. When inflation peaked in 1980, 1989 and 2007, the targeted Fed funds rate required to curb inflation stood at roughly double the Core PCE rate. Today, the Fed funds rate is 0.025% – 0.050%, while Core PCE is at 5.2%. This suggests a Fed Funds rate of 10% is in order, a rate that would devastate the US economy.

An April report by HSBC’s Stephen King contends that the Fed responds far too slowly to mounting inflation because it attributes inflation to a series of exogenous shocks and it believes its own forecasts that show inflation in decline. Many of the drivers of inflation may have begun as external shocks, but now represent structural changes in the economy. Changes in demographics, labor habits, supply chains, consumption patterns, commodities and manufacturing needs have combined for an inflationary cocktail.

Knocking at debt’s door

The Fed’s task made harder by the fact that the US debt-to-GDP ratio, which was around 30% in 1980, sits today at nearly 140%. Aside from a potential debt mess, inflation and rising rates could bring a host of unintended consequences or “black swans”. The first might come from Japan, which has the highest debt/GDP ratio in the developed world. Because of this, the Japanese financial system cannot tolerate higher rates. While the Fed and other central banks are driving rates higher, the Bank of Japan is keeping rates pegged near zero. The US dollar/yen has collapsed to twenty-year lows due to these rate differentials.

Also, Japan is the largest foreign holder of US Treasuries, ahead of China. The currency volatility is causing the cost to hedge the US dollar to surge, which has made US Treasuries unattractive in Japan, despite their much higher yields. According to BMO Capital Markets, Japan has offloaded US$60 billion of US Treasuries over the past three months. Expect more volatility in currencies and rates if Japan continues to sell portions of their US$1.3 trillion hoard of US Treasuries at the same time the Fed is reducing its own trillions in US Treasuries through quantitative tightening.

Other countries might feel the sting of a rising US dollar, too. According to the Bank for International Settlements, US dollar debts owed by borrowers outside the US totaled US$13 trillion as of the last year’s third quarter. These debts become more expensive in local currencies as the dollar appreciates.

Dollar downer

Given the state of the global economy and the state of geopolitics, many gold advocates wonder why the gold price isn’t higher.

Gold has been in a secular bull market since December of 2015 when it bottomed at around US$1,050 per ounce. Gold’s performance so far is no match for the other secular bull markets in the 1970s and the 2000s. The current bull market is being driven by similar macro-economic and geopolitical risks, with some drivers made worse by the pandemic. One stark difference may explain the weaker performance of gold so far in this bull market. The US dollar was in a secular bear market in both the 1970s and the -2000s. From 1971 to 1978, the DXY declined 45% and from 2002 to 2008, it fell 41%. However, since December 2015, the DXY has gained 5.2% as it has bounced around in a sideways trend that is currently testing its twenty-year high. While gold and the US dollar sometimes trend higher together in periods of acute financial stress, the normal relationship is inverse. We believe the firm US dollar has muted gold’s advance in the current bull market.

China and Europe appear to be leading the world into recession and the Fed is leading the charge in rate hikes. This all bodes well for the US dollar, at least for now. Gold also has many drivers. The strong US dollar is creating financial stress elsewhere in the world, it looks like inflation pressures remain and there are geopolitical and economic risks that should continue to drive gold. While we believe gold prices are heading higher, until the US dollar trends lower, gold may not see the spectacular gains of past secular bull markets