by Julian Howard – Lead Investment Director, Multi Asset Solutions

Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu once said that “Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.” Investors appear not to have heeded his call so far this year. Amid a slew of grim developments including war, disease, inflation and rising interest rates, investors have stampeded for the exit. The SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust, one of the largest exchange-traded equity funds in the market at USD 380bn and a good proxy for investor sentiment, has seen net outflows of USD 25bn this year, as at 27 May.

Stepping back from the immediate causes, such reactionary moves are structurally embedded in the modern investment landscape. The marvel of the daily (or even hourly) quotation is accompanied by the curse of information overload that, in turn, influences near term pricing. This can play havoc with investors’ successful achievement of their goals over time. Just as the so-called ‘worried well’ demand repeated tests from their exasperated doctors with no change to long term health outcomes, so too are investors who keep checking their valuations and making changes unlikely to alter anything except their anxiety levels. How then to reconcile the longer term horizons required to meet most sensible investment aspirations with the flood of information investors are bombarded with each day?

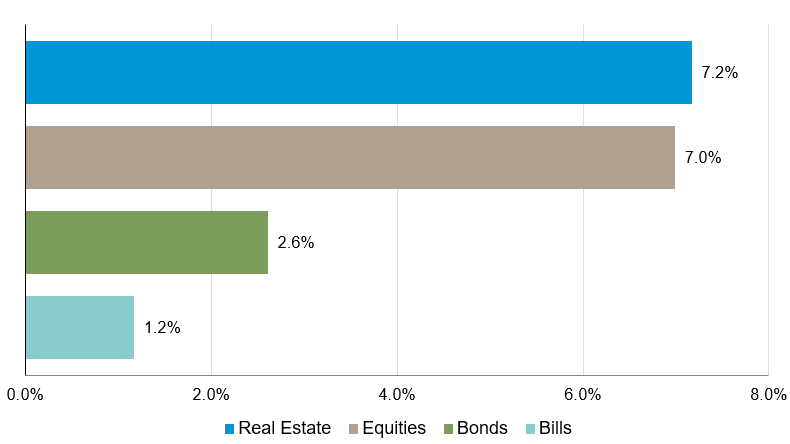

We believe there are two evidence-based ways to achieve this, with the result being a hopefully smoother and less fraught journey to investment effectiveness. One approach involves no longer checking daily pricing and financial news but rather focusing on the long term investment goal. Few studies are as clear on this point as the 2017 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s paper entitled ‘The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870-2015’. This seminal work reveals how, over a near 150-year period, equities generated an annualised return of 7% in real terms. The study’s long time period, which spans a wide range of economic and market disasters from the First World War to the Dot-Com crash to the Global Financial Crisis, gives it credibility – in other words, it is not gamed in any way to capture only a goldilocks period for equities that can be used for making an overly optimistic case for tomorrow. The last two years, dire as they have been, have offered nothing worse than the dramas seen during the 145 years covered by the authors. Furthermore, the study is based on stock exchange and market level data rather than any specific historical investment or trading strategy.

Together, these factors suggest that the overall return from equities is, at its heart, a reflection of human ingenuity articulated in the form of the listed corporate entity. This powerful statement of evidence of what the market can do over time should provide investors with the cool-headed, intellectual reminder they need should they ever waver during episodes of elevated volatility.

Long term real rates of return transcend the worst episodes of 145 years’ history:

Annual global rates of real return, by asset, 1870-2015, %

If that fails to convince, a more practical approach focused on learning from past mistakes could be deployed. Contemporary philosopher, Alain de Botton, said that “Anyone who isn’t embarrassed of who they were last year probably isn’t learning enough.” For many retail investors looking back over the last two decades there is much learning to be done.

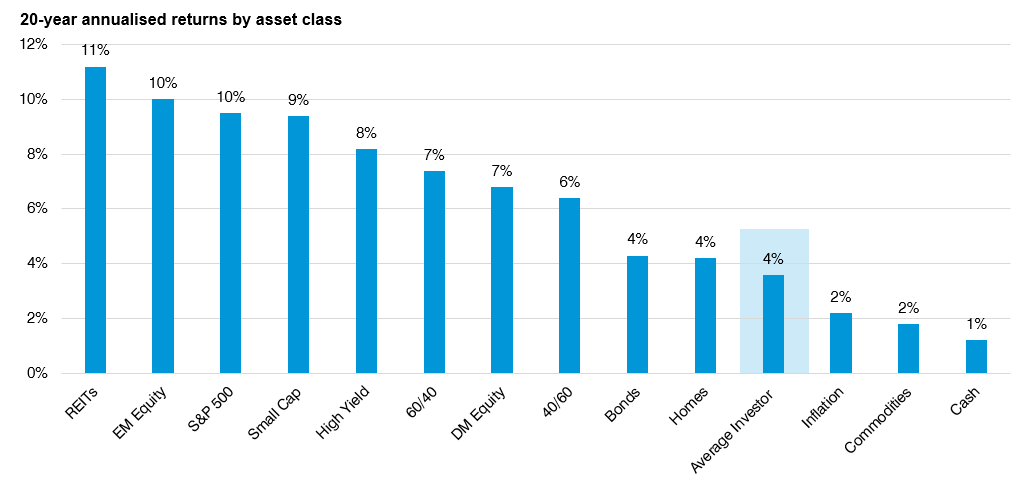

Analysis conducted in April 2022 by research firm Dalbar reveals that the average investor achieved a 4% annualised return over the 20 years to 31 December 2021. This compares with 7% for a fixed 60:40 allocation to equities and bonds, and 10% for the S&P 500 over the same time period.1 A reasonable conclusion might be that many investors are not professionally advised and pursue their own strategies. This is understandable given that individual retail stock accounts are smaller than professionally managed ultra-high net worth or institutional pools of capital.

Unguided, the average investor is especially vulnerable to the cognitive flood of information and prone to more reactionary decision-making. Perhaps for this reason, retail investor flows often correlate pro-cyclically with market movements – strong markets attract inflows while weaker markets prompt outflows. In our view, this embeds a loss-making strategy into investors’ portfolios as they effectively buy high and sell low, as per the continued outflows from the SPDR ETF cited above. This sobering evidence is worth keeping in mind at all times, but especially during volatile periods when the temptation to act is at its greatest.

The perils of (probably) unadvised, reactionary investing:

Data from 31 Dec 2002 to 31 Dec 2021

Improved information and transparency in all areas of life are generally to be welcomed. Consumers want to better understand everything from the carbon policy of their energy supplier to how they can take more control of their own health using technology. But an excess of daily information and choice in the investing world is far harder to translate into better outcomes.

The receipt of almost limitless information can all too easily be confused for a thorough understanding of what is happening, resulting in a misplaced confidence to react to near-term events. In our view, investors may instead consider starting their journey with a one-time portfolio decision that maps their long term planning goals to the realistic and achievable returns available from capital markets. While the temptation is to adjust portfolios ‘along the way’, we believe the most attention should be spent on carefully establishing the most suitable investment strategy at the outset and then regularly reaffirming that suitability. Getting this right is likely to be multiple times more beneficial for investors than adjusting individual holdings in their portfolio as they attempt to weather episodes of near term volatility. Perhaps the real challenge with sticking to the plan is that it remains so disarmingly simple.