So, in June 2022 we saw the US stock market (S&P 500 Index) enter bear market territory, marking a 22% decline from its January peak.

Share prices have bounced around a little since, but the bear market tests of a 20% fall and prices being lower for a significant period of time – almost six months in this case – have been satisfied1.

To put this in a longer term context, the market raced ahead in 2020 and 2021 and even now has only given up a proportion of those gains. Anyone who invested in the US market a year and a half ago is likely to still be up on the deal.

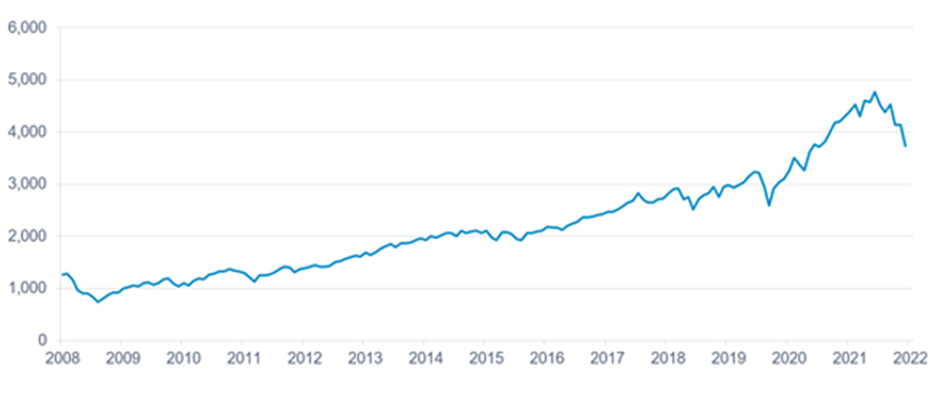

The short and longer term charts of the S&P 500 shown here illustrate this quite neatly, as well as the market’s consistent ability over the long term to bounce back, even after the falls of 2008 and 2020 which, at the time, felt like catastrophes.

S&P 500 short term performance chart

Source: Refinitiv from 15.6.21 to 15.6.22. Basis: Price index in USD.

S&P 500 long term performance chart

Source: Refinitiv from 15.6.08 to 15.6.22. Basis: Price index in USD.

However, the question as of today is where and when will the current dip end – if that is indeed what it is? The actual outcome is likely to lie somewhere between “the market has fallen far enough and is due an imminent bounce” and “something serious is happening and the falls will carry on”.

So, let’s look at three guiding lights for times like these – earnings, interest rates and relative value – to see if the world really is caving in.

On the first of these, the market appears to be on firm footing. Unlike share prices, earnings haven’t shot lower at all. On the contrary, analysts are still expecting the earnings of S&P 500 companies to grow by around 10% in 20222.

Interest rates, of course, are the main concern and the stock market currently seems minded to take no chances in this regard. Rates are rising after two decades of sub-normality, so what we are experiencing is a shock.

This isn’t a shock in the sense of surprise, rather it’s a shock in the sense most people find it hard to remember a time when rates were rising this fast and what happened to asset prices when they did.

The recent 0.75% rise taking interest rates in the US to a range of 1.5% to 1.75% was the largest single hike since 1994 and the Fed made it plain for us to see the potential for the same again next month3.

The bear case for interest rates is that central banks have been consistently behind the curve in taming inflation so rates must now move fast and far.

In a worst case scenario – comparable to conditions in the 1970s – rates have much further to travel because elevated commodity prices – oil, copper, wheat etc. – are here to stay. That risks grinding the economy to a halt and then into reverse.

The bull case is that the inflation we’re seeing today isn’t structural, it’s cyclical, and only signifies temporary price rises as the world rebounds from the pandemic.

Supply chains and the production of commodities will gradually adjust to the new demand patterns of a post-pandemic world, labour shortages will be cured and inflation will revert to low levels.

If that happens, interest rate expectations will also pivot lower, sparking big rallies in both bonds and equities.

This is the essence of the economic debate of the year.

On relative value, the stock market has been losing ground while remaining relatively attractive. Shares have fallen but so have government bonds.

In the US, the expected earnings yield for companies – the inverse of their forward price-to-earnings ratios – is currently about 6%, which is almost twice as high as the yields on 10-year US Treasuries4.

In addition, given that in general shares tend to grow their earnings over time while the yields from bonds are fixed to maturity, shares are potentially the better looking prospect.

It has to be said, however, that these guiding lights do not drive markets over the short term. Sentiment does that, and markets are clearly shaken.

Moreover, under the worst case scenario for inflation described above, further substantial rises in interest rates could tip earnings and relative value into negative territory, so all three factors would then be against us.

So, what should investors now do? Moving more into cash is always an option, though probably not a wise one in the current circumstances.

In the US, interest rates available on deposit accounts aren’t as measly as they were six months ago, but we can still infer a loss in real terms this year of between 7% and 8% (on the assumption US inflation reaches about 9% to 10%).

Second, selling shares today would realise less than what probably would have been achieved six months ago. What’s more, if markets rebound in fairly short order from here – which they potentially could do – investors would be left with the conundrum of when to buy back in.

Leaving it too late could risk missing out on a rise greater than the money saved (if any) on the way down. As the long-term chart of the S&P 500 shows, time in the market, as opposed to timing the market, is potentially the better bet.

This brings us back to the genuinely useful weapons investors have at their disposal. The first is staying diversified across asset classes (including alternatives like gold), geographies and investment styles (growth, value etc.). Over time, that should help insulate a portfolio against the worst effects of market and economic shocks.

The second – money management – is equally important. Other than during the most potent of bull markets, holding back some cash to deploy in the event of a correction is usually a good idea. In fact, as the strongest bull runs are usually as unpredictable as any other kind of market action, keeping some powder dry should be considered a universal maxim.

By extension, saving regularly is also a useful tool. Investing the same amount in stock market investments each month automatically ensures that more fund units or shares get bought after prices have fallen; fewer do after a big market rise.

Again, over time, this strategy tends to work out very well. Its limitation is that it takes time to deploy large lump sums this way. However, if you want to minimise your exposure to market timing, it has few peers.

Source:

1 Bloomberg, 16.06.22

2 FactSet, 10.06.22

3 FT, 15.06.22

4 FactSet, 10.06.22