by David Dowsett – Head of Investments

We believe the coincident crises of the pandemic and the Russia / Ukraine conflict will act as catalysts for a structural change in the investment environment. Many of the structural themes we have grown used to over the past four decades are set to change, and we think it is imperative that investors reset their thinking in order to benefit.

Globalisation promoted an era of low inflation, connectivity and mobility. This was sponsored by governments eager to escape the post Bretton Woods economic chaos of the 1970s. Most importantly, returns to capital were prioritised over those to labour. Economic stability was seen as essential in order to unleash productive private sector investment. This became a global creed, beginning in the UK and US, spreading to all corners of the planet and including the greatest economic miracle in history in China.

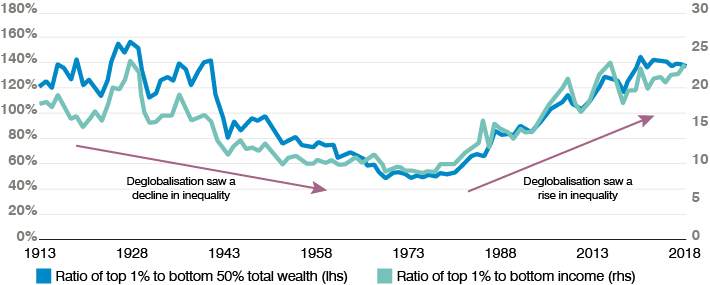

The downsides to globalisation have become increasingly obvious over the past decade. Increasing inequality, and the awareness of it by hyper connected global netizens, has led to a political backlash most obviously manifest in Trump, Brexit, Five Star, the “gilet jaunes” and the global surge in populism. However skilled these populist leaders have been in capturing outrage, though, they have been unable to offer a practical alternative.

The pandemic and a European war have suddenly given us clarity. Lockdowns meant key workers were those in our local hospital, school and supermarket, not faceless guardians of international capital. The most important community was your most local one. The conflict in Ukraine has destroyed many of the previous certainties of the post-Cold War era. As a consequence, global capital flows and supply chains can easily be interpreted as a source of weakness rather than a rational division of labour.

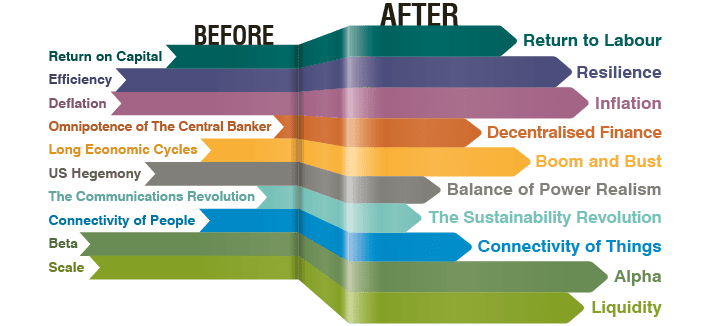

We have identified 10 key themes where we think there will be a material “before and after” the 2020-22 crisis period. Our intention is to introduce these themes below, before following up in more detail in forthcoming articles.

The first, and most profound and overarching theme, is that economic policy will transition from prioritising the return on capital to safeguarding the return to labour. During the pandemic the essential value of labour was starkly revealed. The Covid policy response prioritised the essential worker over the knowledge worker. There is a renewed awareness that our most important workers, those who keep society functioning, are those in our local communities. Governments will continue to respond to this realisation. European furlough policies and the CARES Acts in the US were the most pro-labour policies initiated since World War 2. This consequent fiscal expansion was unquestioned and there is no political appetite for a corrective return to austerity.

Chart 1: The transition from return on capital to return to labour

Related to this will be an emphasis on resilience rather than efficiency. Just in time global supply chains do not appear so clever when it means your health system does not possess the requisite stock of PPE. Slack and extra supply will be seen as a necessary buffer and diversifier against unforeseen events. Essential local services cannot be offshored. National resilience is also a virtue in a more unfriendly world. The law of the market may have determined that 92% of the world’s most advanced computer chips are made by one company in Taiwan1 but the inherent vulnerabilities are now obvious.

As a consequence of these developments, we are now moving from an era of deflation to one of inflation. As a result of the opening of China and the emergence of market economies in Eastern Europe, between 1991 and 2018 the effective global labour force more than doubled. This is a one time shock that is now behind us. There is still an abundance of labour in Africa, but an adoption of efficient manufacturing techniques that made China such a deflationary force do not seem imminent. As supply chains are regionalised or nationalised domestic workers will have more wage bargaining power.

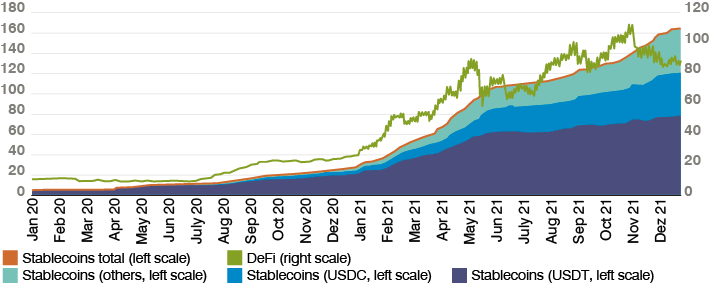

The era of globalisation has led to the personality cult of the central banker. The trend for central bank independence gave monetary officials extraordinary autonomy and power and they have not been slow to exercise it. Former Federal Reserve (Fed) chair Ben Bernanke was a far more proactive firefighter after Lehman Brothers than the federal government. Mario Draghi, former president of the European Central Bank (ECB), saved the euro, not Merkel. This monetary policy experimentation reached its apogee during the pandemic, when the Federal Reserve bought over USD 600 billion of US Treasuries and mortgages in the last week of March 2020, at a rate of a million dollars per second. Monetary policy activism has arguably increased inequality as most of the extra liquidity has been invested in financial assets and facilitated buybacks rather than trickled into the real economy, but central banks have been able to act because there has been no inflationary constraint. Those times are changing. The era of the omnipotence of the central banker will likely be replaced by an era of decentralised finance. You will find no judgement here on the current value of Bitcoin, Ethereum or Dogecoin but “proof of work” and “proof of stake” concepts are valid attempts to establish a digital ledger through the blockchain. Such ideas will only gain popularity for those concerned about perceived monetary debasement and government overreach. Governments will almost certainly join the race too. Central bank digital currencies will be seen as a way to lessen excessive reliance on the US dollar in the global funding system. We are only at the very early stages of digital financial innovation.

Chart 2: The rise of assets in decentralised finance has accelerated in recent years, driving growth in stablecoins

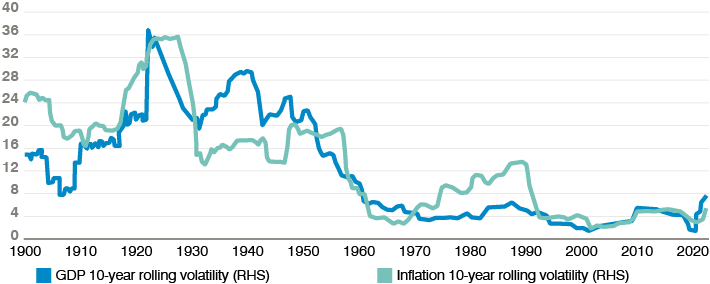

All of the above forces will contribute to a change in our expectations over the length of the cycle. We therefore believe long economic cycles will be replaced by boom and bust. The economic expansion between 2009 and 2020 in the US may have been underwhelming, but it was the longest on record, going back to the 1850s. Prior to that the longest expansion on record was between Q1 1991 and Q1 2001, another period of low inflation. As resource constraints increase, the importance of the quality of monetary and fiscal policy decision making increases. This may prove difficult in today’s polarised political climate. The overkill of the 2021 American Rescue Plan, costed at USD 1.9 trillion into an economy that was already strongly recovering post Covid, may be one example of that. A preview of the stresses to come may be seen in that fact that Germany is currently experiencing its fastest inflation rate since the 1950s, while ECB interest rates are still negative. The policy making challenge just got a lot harder.

Chart 3: US GDP vs inflation 10-year rolling volatility

The economic transition will be accompanied by a geopolitical transition. Globalisation has witnessed terribly violent events, most notably 9/11 and the ensuing turmoil across the Middle East but inter-state conflict has been limited. All major economies seemed to benefit. We have had a wake up call. The Russia / Ukraine conflict brutally demonstrates that territorial questions in Europe have not been definitively settled. The struggle for influence and power in Asia has just begun. An increasingly confident China may want to assert its claim to regional hegemony. Other local powers, supported by the US, will likely push back. Confident predictions seem foolhardy, but it looks like the Pax Americana is definitely over. US hegemony is likely to be replaced by regional balance of power politics. Investors should expect increased inter-state tensions, with all of the consequent uncertainty for trade and capital flows.

Chart 4: Chinese strategic view of the PRC’s security environment

Aside from macroeconomic and geopolitical issues, the investment megatrend accompanying globalisation has been the communications revolution. The corporate symbols of globalisation are those companies who have utilised an explosion in computing power to connect people to share information and product. Witness the rise of the FAANG stocks in the US and Baidu, Tencent and AliBaba in China. The iconic product of globalisation has been the iPhone, conceived in the US and made in China. Used by consumers around the world to access their social media echo chambers which have reinforced division and heightened awareness of the inequality that has been the inevitable by-product of a global economy. The technological and communication revolution has also been inherently deflationary. Moore’s Law instructs that you can get more for less. The communications revolution will not end, but will replaced as the investment megatrend by the sustainability revolution, in our view. The pandemic has heightened our sense of our planet’s fragility. The need to address climate change is the greatest technological challenge and investment opportunity of the rest of our lifetime. The societal, governmental, regulatory and basically existential imperative will mean a global investment tidal wave directed towards all forms of renewable energy and consumption. The West may lead the way in active stewardship but expect most exciting product development to occur in Asia. Sustainable innovation will accompany the global centre of economic gravity in moving East.

Chart 5: Investment into renewables and other energy transition

As discussed above, the connectivity of people has had profound effects on our society and politics, but there is a feeling we have reached saturation point. The regulators are poised and the detrimental mental health effects of social networks are just beginning to be understood. Our lives will change in a different way as the connectivity of people is overshadowed by the connectivity of things. Computing power, better network coverage and advances in robotics and AI will allow convergence of our digital and physical worlds. This will likely result in developments that many of us may not see (factory automation) and those which change our lives in very direct ways (health sensors). Autonomous vehicles offer us a tantalising vision of the future.

All of these changes necessitate a psychological reset for investment decision making. They also signal that the components of return will change. Active central bank policy, dollar dominance and low inflation have led to rising correlation of returns across all asset classes. How often have investors been frustrated by a “risk on / risk off” mentality driven only by changing expectations of Fed policy in its role as global liquidity provider? The secular decline in government bond yields has led to a generalised beta trade as investors have incrementally extended along the risk curve. Perhaps not surprisingly we are now witnessing an indiscriminate sell off as short-term expectations recalibrate. More meaningfully, for the long term, we expect sources of beta to be replaced by the search for alpha among successful investment strategies. Returns will become less directional and more differentiated. Manager skill will require distinguishing between good and bad business models rather than those that surf a global tidal wave of liquidity. Manager selection will assume heightened importance.

In the asset management industry, as in many others, the most recent era has been one that rewarded global platforms able to take advantage of scale. The biggest asset management firms have grown exponentially larger. Breadth of product has seemed more important than specialised expertise. In the more volatile and differentiated markets to come ability to manage liquidity will be more important than the advantages of scale. We believe that in order to succeed asset managers will need flexibility and agility. Central banks will no longer act as implicit buyers of last resort. We believe investors will need to be comfortable in their own ability to exit positions, with no outside help. Being the largest investor in an asset class will more likely be a disadvantage rather than a weapon which can be used to dictate terms.

A different world

We have set out above the world we see emerging from the crises of the past two years. It is important to stress that this world is not necessarily better or worse than what happened before; it is simply different. If we are right in our analysis, and we approach the new environment sensibly and proactively, the investment benefits could be significant.