by Ross Cartwright – Director, Investment Solutions Group

The value versus growth debate is now largely moot: Investors want to buy stocks that offer good value and grow.

While there are different approaches within each style, value is associated with buying cheap stocks and growth with fast-growing businesses. While some approaches focus on the extremes, the reality is that many investors are situated somewhere along this continuum. There are times when growth stocks are undervalued and times when numerous value stocks offer strong growth opportunities. We believe that irrespective of the label, companies that are good stewards of capital will expand over time, which can make them good long-term investments.

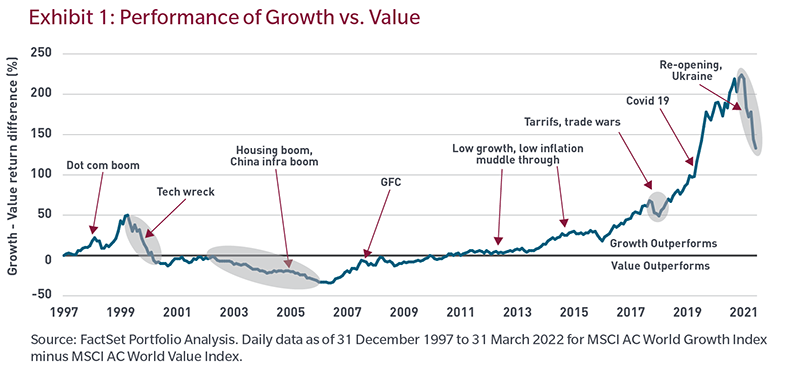

Following an extended period of growth dominance, the investment landscape is changing, and we think investors may want to reset their expectations for each style and what they can provide.

Growth investing

The growth investor is looking for companies that can grow their earnings at a high rate or companies that have no earnings but compelling reasons to believe that it could generate a lot of earnings in the future. Fast-growing companies generally have not paid large dividends as they need the cash to fund their growth.

Growth stocks are often thought of as expensive, since they generally have traded at high price-to-earnings multiples as investors were willing to pay up for their growth. In our view, potential success relies on the company growing earnings and the market, at a minimum, supporting the stock’s premium valuation. Regardless of the fundamentals, growth stocks gains have often been fuelled by speculation, momentum, and excess liquidity.

Misjudging the growth rate of high-multiple or long duration growth stocks can be extremely painful because sentiment can turn quickly, as we have seen over the past few months.

Value investing

Traditional value managers try to identify companies that are discounting their growth prospects or whose earnings may be depressed for an idiosyncratic reason, an example being their stock trading at $50 when an investor believes it will be worth $100 if the company executes its plan. The value investor believes that the company’s earnings will recover and that when the market recognizes this its multiple will expand along with earnings. Value companies normally grow slower than their growth brethren and dividends typically play a greater role in the value investor’s return as value companies are typically more mature and return excess cash f lows to their investors.

Value managers generally enjoy the advantage of a valuation cushion: For instance, if sentiment turns negative, the stock’s multiple may fall, but because it is usually already low relative to the market — or the company’s history — the fall may not be as severe as with a growth company. However, value managers may f ind themselves in a “value trap” wherein the market never recognizes the earnings recovery or the value of the company’s assets, or the firm’s earnings potential continue to decline so the stock gets even cheaper as the multiple compresses further.

What drives returns?

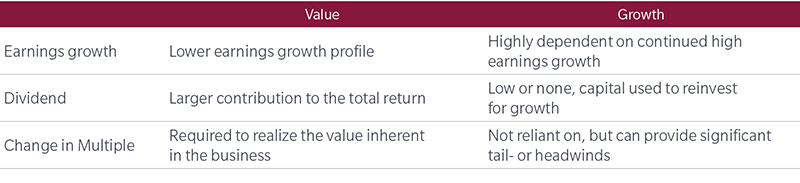

The return on any stock is generally made up of three components: earnings growth, dividends, and the change in P/E multiples. In the long run, it is the earnings growth and dividend that drive returns. The multiple, the price an investor is prepared to pay for these cash flows, is a function of short-term sentiment. As the table below shows, a stylized view of how the different approaches target different drivers of stock return.

We believe trying to time value exposure is extremely difficult. As a value investor you do not know how long it will take or when other investors will uncover the opportunity. An active manager who has assessed the risks may be confident that the market will reward its recovery. However, the timing is uncertain. To reap the potential benefits of the value process, you need the patience and independence to let the manager’s thesis plays out.

Growth investors are subject to sentiment or momentum as the expectation of future growth feeds on itself and investors willingly pay higher and higher multiples for it. As with a value investor, a growth investor does not know how long sentiment will support the process or when it will suddenly reverse, as it often does.

We believe a well-constructed, multi-manager equity portfolio consists of a mix of underlying strategies that can provide returns at different times in the cycle but independently strives to outperform its benchmark over the full market cycle, thereby potentially maximizing the portfolio’s information ratio. Having a strategic exposure to the different drivers of return that are offered by value and growth potentially strengthens a portfolio. We think unpredictability of sentiment, and the speed at which it can turn, further supports the argument for maintaining a strategic exposure to both the growth and value styles of investing.

Will higher rates and inflation help value managers?

Unsurprisingly, value stocks have been somewhat correlated with higher inflation. Inflation has usually been a result of rising prices for inputs such as energy, raw materials, food and labor. Traditional value stocks dominate cyclical sectors such as commodities, energy, industrials and financials, so when demand is strong and prices for raw materials or fuel are going up, companies that produce these commodities tend to be more profitable and see their stocks re-rate on higher future earnings expectations. The driver of their performance is also driving inflation.

Inflation reduces purchasing power, potentially pulling forward capex as companies prefer investing now, when they know the price, to investing in the future, when the price is uncertain. This has tended to support more capitalintensive value-type names.

Reduced purchasing power impacts companies whose expected cash flows are further off in the future more than those with near term earnings, hence growth that relies on future earnings has typically been a weaker performer than value when inflation is higher.

Impact of interest rates on valuation

Historically, there has been a link between inflation and interest rates. Higher inflation has typically been followed by higher rates as central banks raised rates with the intention of slowing down demand to reduce upward pressure on prices. Increasing interest rates has a direct impact on valuation, as does slowing demand.

If a company is worth the sum of its future cash flows (earnings plus dividends), then increasing the interest rate (the discount rate in a discounted cash flow analysis) reduces the value of those cash flows, and the further into the future the cash flows are, the greater the potential negative impact on valuation. Both growth and value stock valuations are impacted by higher rates. However, the impact on growth stocks is larger because the cash flows driving the valuation typically come much later than for value stocks.

Government bond rates are not the only input into a discounted cash flow model. A discount rate used on any stock valuation needs to account for risks associated with the company beyond the risk-free rate. High or low interest rates will not help if you get the cash flows wrong. In a rising rate environment, value stocks could have a tailwind relative to growth stocks, but it is the anticipated impact of rising rates on the outlook and expectations of future cash flows that can have the greatest impact on valuation.

Higher rates have traditionally been beneficial for another value sector: banks. Rising interest rates should help banks increase margins earned on the spread between the rate at which they borrow and what they charge customers. However, the earnings power of banks has been restrained by regulation and a flat yield curve, so today’s rising rates may not be as helpful as they have been in the past. Added to this, rising rates are intended to slow the economy, thereby reducing lending and economic activity, which is negative for banks, who rely on credit growth to increase earnings. While higher rates are supportive for banks in general, the current climate may warrant selectiveness across the sector in terms of their exposure to both how they fund their loan book and the underlying economic exposure of the book.

Is now the time for value?

Value-style companies are often cheap relative to the market because of the risks associated with their cyclicality and business models. Many of these businesses generally expect their earnings growth and valuation re-rating to come from a change in a commodity price, an interest rate or a factor outside of their control. These businesses have done well as the world has reopened after COVID lockdowns, and more recently, on commodity supply constraints due to the Ukraine conflict. Much of this is now priced into value stocks. However, we feel there are some pockets where constrained supply will continue to support higher prices without significant falls in demand, albeit not for all commodities. Longer term, the supply function will adjust as any excess profits draws in more capital.

In our view, a value approach that favors businesses under-priced for idiosyncratic reasons may be better for managing an economic slowdown, and potentially providing a dividend and valuation support to a portfolio, than an approach relying on cyclical sectors that are perennially “cheap” relative to the broader market. Companies that have capital invested in real world plant and equipment may well be better placed than those requiring external capital to keep growing. After many years of underinvestment, decarbonizing the world’s energy sources, refocusing supply chains, capex and onshoring strategically important industries may provide an improved risk/return profile to many of these traditional “value” businesses.

Will growth stocks rebound?

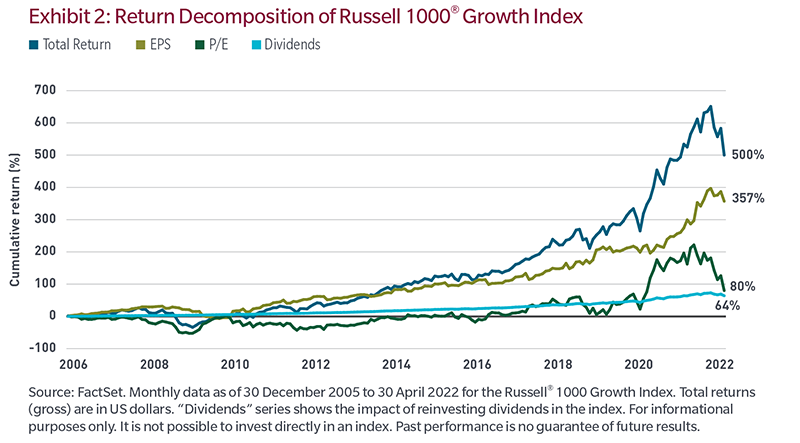

The chart below highlights how two years of loose monetary and fiscal policy drove speculation as P/E multiples expanded in growth stocks, turbocharging returns on blue sky earnings projections. Now, weaker economic growth expectations have caused growth multiples to collapse. Tighter financial conditions and reduced liquidity are increasing the cost and decreasing the availability of capital. In this environment, we expect the focus of managers to change from raising cheap capital and financializing balance sheets to fund growth to prudent capital allocation to drive profitability, as well as reinvesting in their businesses’ future.

Unless inflation falls or unemployment rises quickly, the US Federal Reserve, based on their statements to date, is unlikely to step in and support asset prices. We think a broad rebound in high-growth stocks aided by significant multiple expansion will probably not occur under these conditions. The quality of the high-growth companies whose stocks that have capitulated over the past six months ranges from poor to excellent. However, a change in sentiment like the one we have just experienced has usually resulted in “the baby being thrown out with the bathwater”, or more plainly, good-quality companies being dumped along with bad ones. Some of these businesses will recover as they continue to deliver strong growth. Our job is to attempt to identify the great ones trading at great prices.

Conclusion

We believe a solid, potentially all-weather equity portfolio should be built around how the underlying strategies target different drivers of equity return and an appreciation of the risk/reward profile they bring and not on uninformed decisions. Different points in the economic cycle will provide broad headwinds or tailwinds for each style. However value style exposures without differentiating the potential cyclical effects across sectors may potentially lead to exposures to cyclicality and structurally challenged, or poorly managed industries and companies.

In our view, it is not always easy to tell skill from luck, and investor psychology is usually volatile. Holding deepvalue cyclical stocks may well be an objective, but an appreciation of the return pattern that doing so provides, is also important. While the general climate for value stocks may have improved, identifying idiosyncratic value opportunities may provide dependable but less cyclical exposure to value opportunities and return drivers.

We feel strong fundamental analysis requires teams that look at the issues from a variety of perspectives, allowing them to better account for the ways outside influences, from technological disruption to regulation to financial market dynamics, affect businesses and their share prices.

The seismic shift over the past few years has been the rotation to value after substantial initial support for growth. But the attributes that have supported each of these regimes is changing, and as we witness a rise in cross-sectional dispersion, we believe it will not be bookends of growth or value that drive future outcomes, but rather companies with desirable products and services, higher barriers to entry and the ability to protect their margins, allocate capital wisely and provide good stewardship. We believe these companies will prosper, whether they fall into the value, growth or somewhere-in-between camp.