Introduction

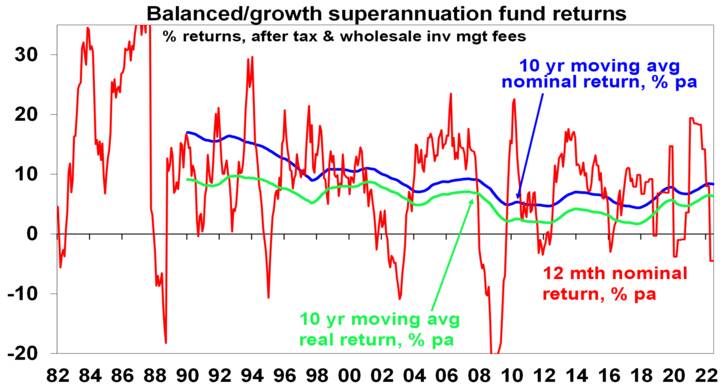

The start of this year has been painful for investors with sharp losses in shares and bonds, dragging most superannuation funds into negative returns for the last financial year. And yet despite this setback and rough patches in 2015, 2018 and in early 2020 with pandemic lockdowns, median balanced growth superannuation funds returned 8.4% pa over the 10 years to June after fees and taxes. While dull compared to the double digit returns of the 1980s and 1990s, it’s pretty good once low average inflation of 2% pa over the last decade is allowed for.

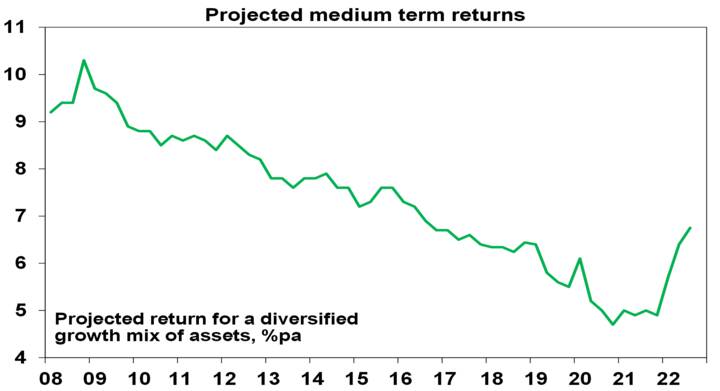

Source: Mercer Investment Consulting, Morningstar, AMP

However, returns have been boosted for decades by a “search for yield” as interest rates collapsed with falling inflation. This pushed down investment yields (bond yields, earnings yields on shares, rental yields on property, etc) and so pushed up asset values. But the sting in the tail was that ever lower yields meant an ever lower return potential for when yields eventually stopped falling. The good news in the recent fall in markets is that it’s pushed potential medium term returns back up a bit.

Lower yields = lower return potential & vice versa

Investment returns have two components: yield (or income flow) and capital growth. What gets confusing though is that the price of an asset moves inversely to its yield all other things being equal. For example, suppose an asset pays $5 a year in income and its price is $100 – this means an income flow or yield of 5%. If interest rates on bank term deposits are cut from say 3% to 1% this will likely encourage increased investor interest in the asset as investors will like its relatively high yield. Its price will then be pushed up – to say $120, which given the $5 annual income flow means that its yield will have fallen to 4.2% (ie, $5 divided by $120). This is great for investors who were already in the asset as its value has gone up by 20%. But its yield is now pointing to lower potential returns going forward (ie, 4.2% which is down from 5%), unless the yield continues to fall further boosting capital growth. But of course, there is a limit to this & it also works in reverse as maybe we are now starting to realise with the surge in inflation over the last year, which is pushing up interest rates, bond yields & yields on other assets.

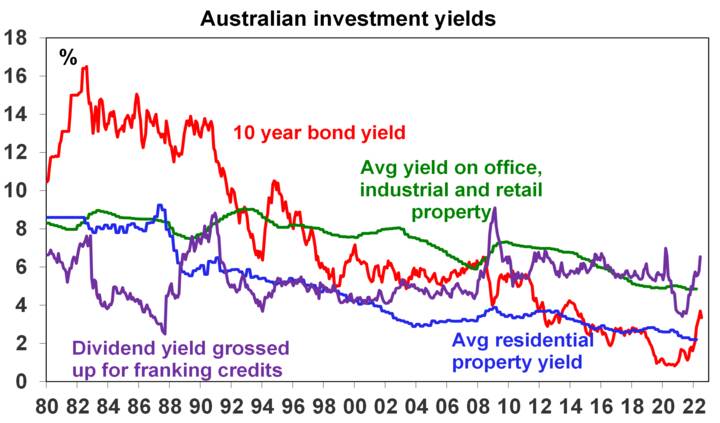

The plunge in yields since the early 1980s

In the early 1980s, the RBA’s “cash rate” was around 14%, 1-year term deposit rates were nearly 14%, 10-year bond yields were around 13.5%, commercial and residential property yields were around 8-9% and dividend yields on shares were around 6.5% in Australia and 5% globally. This meant investments were already providing very high income so only modest capital growth was needed for growth assets to generate good returns. And then with the shift from very high inflation in the early 1980s to very low inflation up until recently, the last 40 years saw a collapse in yields. This was led by falling interest rates and then yields on other assets were pushed down too. See the next chart. Consistent with the explanation in the previous section this led to strong average returns for diversified investors through the last 30 or 40 years, despite periodic setbacks like the 1987 crash, the tech wreck and the GFC.

Source: Bloomberg, REIA, JLL, AMP

At their recent low point the RBA’s official cash rate fell to 0.1%, average bank 1-year term deposit rates fell to 0.25%, 10-year bond yields fell to 0.6%, gross residential property yields fell to 2.2%, commercial property yields fell below 5%, dividend yields fell below 4% for Australian shares (with franking credits) and just 2% for global shares. The problem was that with the cash rate and bond yields around zero there wasn’t much further for yields to keep falling. This saw our assessment of nominal medium term return projections for a balanced growth mix of assets fall below 5%. The good news is that with yields on cash, bonds and shares now up and asset prices down their return potential has improved.

Medium-term (ie, 5 to 10 year) return projections

Our approach to get a handle on medium-term return potential of major asset classes is to start with current yields and apply simple and consistent assumptions regarding capital growth. We also prefer to avoid forecasting and like to keep it simple.

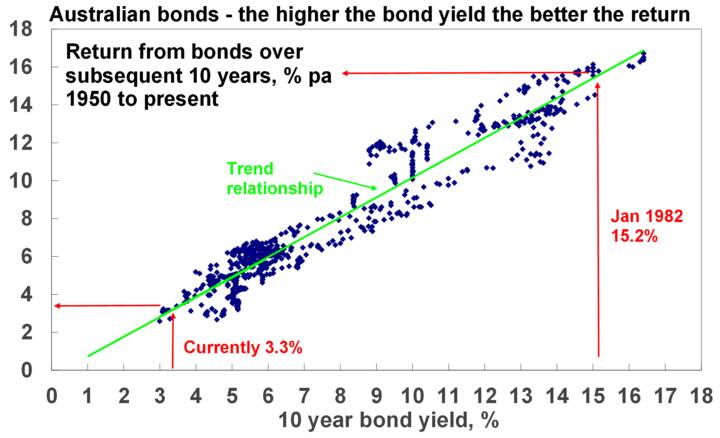

- For bonds, the best predictor of future medium-term returns is current bond yields – as can be seen in the next chart. If a 10-year bond is held to maturity its initial yield (3.3% right now in Australia) will be its return over 10 years. This is still low historically but well up from a low of just 0.6% in 2020.

Source: RBA, Bloomberg, AMP Capital

- For equities, current dividend yields plus trend nominal GDP growth (a proxy for capital growth) does a good job of predicting medium-term returns.1 The Australian dividend yield is up by more than 1% from late last year.

- For property, we use current rental yields and likely trend inflation as a proxy for rental and capital growth. The surge in online spending and “work from home” means greater than normal uncertainty around these returns at present.

- For unlisted infrastructure, we use current average yields and capital growth just ahead of inflation.

- In the case of cash, the current rate is of no value in assessing its medium-term return. So, we allow for our forecast cash rate over medium term.

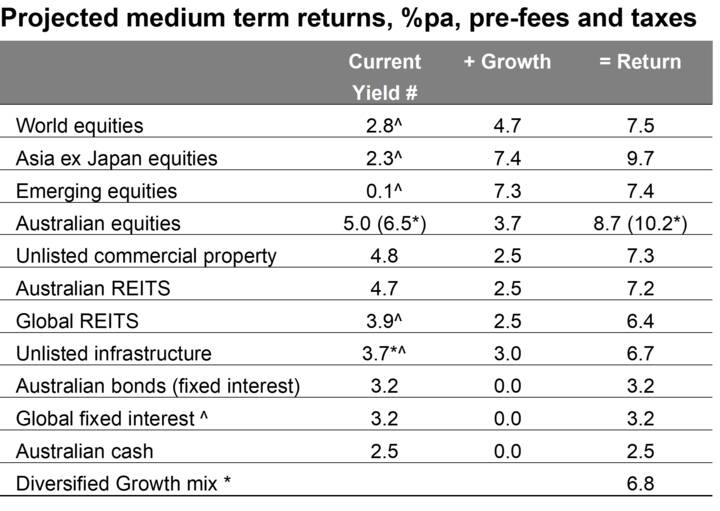

Our latest return projections are shown in the next table. The second column shows each asset’s current income yield, the third shows their 5-10 year growth potential, and the final column shows their total return potential. Note that:

- We assume inflation averages around 2.5% pa, and this has been revised up from 1.5% pa (after years of low inflation pre-pandemic). We are assuming that central banks are successful in bringing inflation back to around target and keeping it there on average over the next 5-10 years.

- We have cautious real economic growth assumptions reflecting the: retreat from globalisation, deregulation and small government in favour of populist, less market friendly policies; rising geopolitical tensions between the West and China/Russia; and aging populations and slowing population growth – resulting in slowing labour force growth. All of which will likely constrain capital growth for growth assets.

# Current dividend yield for shares, distribution/net rental yields for property and duration matched bond yield for bonds. ^ Includes forward points. * With franking credits added in. Source: AMP

Key observations

- After falling for many years due to the fall in starting point yields for major assets the medium-term return potential using this approach fell below 5% in late 2020 but has improved this year to nearly 7%. This is partly due to a 1% higher medium term inflation assumption, but the rest is due to the rise in interest rates, bond yields and yields on assets including shares over the last year. This is the silver lining to the cloud (or rather storm) that has hit investment markets.

Source: AMP

- The return potential from commercial property and infrastructure has not improved much because their yields have not risen unlike those for bonds and shares (as their valuations lag). There is also greater uncertainty in the demand for office and retail space as the full impact from working from home and on-line retail is yet to impact rents.

- The return potential of bonds is still poor but with now higher bond yields its well up from the lows of the last two years.

- Australian shares stack up well on the basis of yield and Asian shares stack up well for growth potential.

- The main downside risk to our medium-term projections is that inflation trends even higher driving a further trend rise in interest rates, bond yields and yields on other assets (including property & infrastructure) resulting in an ongoing drag on capital growth (ie, further reversing the “search for yield” driven surge in values over the last 30 years or so).

Implications for investors

- First, bear markets are painful and are hard to predict, but they do push up the medium-term return potential of shares and so provide opportunities for investors.

- Second, have reasonable return expectations. Interest rates and investment yields are still historically low so its unreasonable to expect sustained double-digit returns.

- Finally, focus on assets with decent sustainable income flow as they provide confidence regarding future returns

1 Adjustments can be made for: dividend payout ratios (but history shows retained earnings often don’t lead to higher returns so the dividend yield is the best guide); the potential for PEs to move to some equilibrium level (but forecasting the equilibrium PE can be difficult and dividend yields send valuation signals anyway); and adjusting the capital growth assumption for some assessment regarding profit margins (but this is hard to get right). So, we avoid forecasting these things.