“Productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything”.

Paul Krugman

Introduction

A hot topic in recent years in Australia amongst economists and policy makers has been the slowdown in productivity growth. This matters because as Paul Krugman points out “a country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.” Productivity is the key to driving real wages growth, real profit growth and asset price growth over long periods of time. It enables governments to boost service provision – in health, aged care, disability, defence etc – without raising the overall tax burden. And it can help keep inflation down. But its rate of increase has been slowing down leading to much angst about what to do about it. Despite lots of talk there hasn’t been a lot of action in addressing the problem over the last 15 years. This may be changing.

What is productivity growth?

Productivity refers to the level of economic output for a given level of labour and capital inputs. Increased productivity means more is being produced for a given level of inputs. The concept of output usually referred to is Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and at its broadest inputs are both labour (hours worked) and capital (ie, buildings, structures & machinery). Dividing these inputs into the former gives “multi factor productivity”. However, its more common to see measures of labour productivity referred to – ie, GDP per hour worked – as they relate to growth in material living standards.

Productivity growth over time

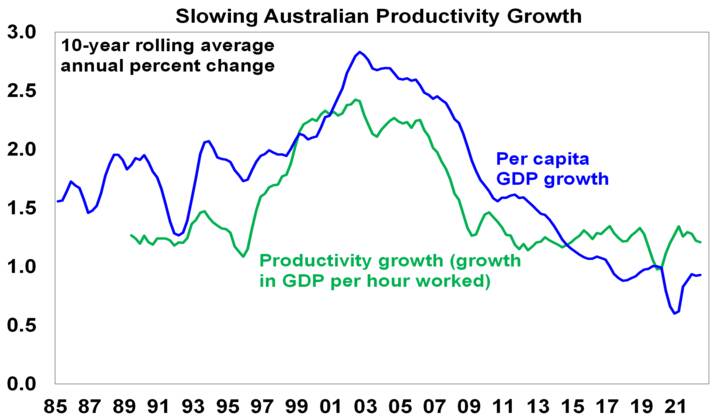

The next chart shows the annual rate of labour productivity growth (ie, the change in GDP per hour worked) since the mid-1980s. It’s shown as a 10-year trailing average so we can focus on the trend. Productivity growth rose to over 2% pa through the 1990s into the 2000s, but it’s slowed to 1.2%pa over the last decade.

Source: ABS, AMP

Productivity growth and living standards

As can be seen in the last chart, the longer-term pattern in labour productivity growth has correlated with a similar pattern in growth in GDP per capita (or GDP per person). Roughly speaking the slowdown in productivity growth from 2.2% pa in the 1990s to 1.2% pa over the last ten years means that after a 10-year period annual GDP will be 9% (or $300bn less in today’s dollars) than would otherwise have been the case, which means much lower average material living standards compared to what otherwise could have happened. Of course, we can make up for the drag on GDP growth by growing the population faster as has been the case since the mid-2000s but this does not address the negative impact on material living standards per person. Lower productivity growth translates to lower real wages growth, slower growth in profits and a reduced ability for the government to provide services that the community expects without taking on more debt.

What’s driven the slowdown in productivity growth?

After the malaise of the 1970s which saw high inflation, high unemployment and low productivity growth, the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s saw a range of economic reforms in Australia designed to improve productivity growth – by making the economy more flexible and competitive, improving incentives and improving skills. These were often referred to as supply side reforms. This included financial deregulation, floating the $A, labour market deregulation, product market deregulation, reduced trade barriers, competition reforms, privatisation, tax reform and an improvement in educational attainment. This, along with baby boomers reaching their peak productivity years, saw productivity growth surge through the 1990s into the 2000s. But since then, a range of factors have contributed to slower productivity growth:

- The boost to productivity from the economic reforms of the 1980s to the early 2000s have worn off.

- Since the introduction of the GST there has been little in the way of significant new reforms and, in some areas, backsliding – eg, labour market changes which introduced a better off overall test for new Enterprise Bargaining Agreements have a seen a decline in the Enterprise Bargaining system, which is likely to have slowed productivity growth.

- Very strong population growth from the mid-2000s with an inadequate infrastructure and housing supply response led to urban congestion and poor housing affordability which contribute to poor productivity growth (via increased transport costs, increased speculative activity around housing diverting resources from more productive uses, households trapped with excessive debt and financial stability issues).

- Just as the entry of the baby boomer wave into the workforce in the 1970s slowed productivity (as new workers are usually less productive) their retirement and replacement with a wave of millennials and Gen Z may drive slower productivity growth.

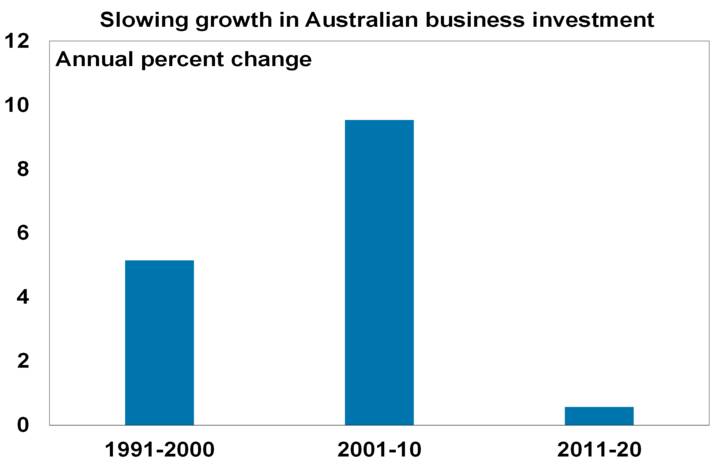

- Growth in real business investment growth fell from 5% pa in the 1990s and 9.5% pa in the 2000s to just 0.6% pa in the 2010s and the last 15-20 years have seen declines in research and development investment as a share of GDP.

Source: ABS, AMP

- The services sector has grown as a share of the economy and its harder to raise productivity in services industries.

- Market concentration has increased, reducing competition.

- Confusion regarding climate policies has likely contributed to underinvestment in power supply, driving high energy costs.

The impact of this may have been masked through the mining boom years. But given increased risks around China – geopolitical risks and medium-term threats to Chinese growth from its property downturn and increased government involvement in its economy – we cannot rely on strong Chinese demand and commodity prices boosting national income indefinitely. And mining sector strength seems to have had a less beneficial impact recently (as measured by a rising mining sector profit share of GDP but a falling wages and non-mining profit share) which may lead to increased social tensions. And now real wages are falling rapidly.

What to do about it?

There are no quick and easy fixes. Simply boosting wages growth to match or exceed current high inflation may provide a short-term feel-good factor, but as we saw in the 1970s this would just run the risk of a wage-price spiral, the end result of which would likely be higher unemployment. The key is to acknowledge the problem, explain the options to Australians and then chart a path forward to boost productivity and growth in living standards. In recent years numerous reports – notably the Productivity Commission’s 2017 productivity review – have looked at what needs to be done. Key areas for action include the following:

- Labour market reform to relax the “better off overall test” to reboot Enterprise Bargaining. Fortunately, the Government, following the Jobs Summit, is moving down this path.

- Measures to boost workforce capability – with more skills training and reforms to raise education standards. This could involve more incentives for training by companies and a greater focus on teacher proficiency.

- Maintain high levels of infrastructure spending to reduce urban congestion, lower transport costs and allow more Australians to relocate expensive housing in big capital cities.

- Boost the supply of housing to more than match underlying population driven demand for several years – this is limited in the short term by building supply constraints, but longer term requires a focus on more efficient planning and approvals, making it easier for institutional involvement in the provision of social build to rent housing and decentralisation. Housing affordability and supply should be key considerations when setting immigration levels.

- Competition reforms to reduce market concentration.

- Better healthcare by focussing on prevention & management.

- More incentives to boost investment and innovation – although such policies have not been overly successful in the past.

- Reduce climate policy uncertainty – in order to encourage more energy investment. The Government is moving down this path which should boost investment in renewable energy.

- More efforts to simplify regulations and remove redundant regulation. The tendency is for regulation to mount whenever there are problems in an industry, but this seems to replace one problem (say poor advice from some financial advisers) with another (eg, unaffordable financial advice for many).

- Remove areas of protection that remain but serve no purpose other than to raise taxation revenue.

- Limit the size of government – disability insurance and more spending on the aged, health and defence are all generally supported by society. But it also needs to be recognised that the progression to ever high government spending as a share of GDP (as we have seen lately) can lead to lower productivity growth so a tight rein may need to be kept on other areas of government spending.

- Tax reform – the Australian tax system has a high reliance on inefficient income taxes, a GST levied on a declining portion of the economy, distorting taxes like stamp duty and the absence of super profits tax on resources. So ideally tax reform should include: a rebalancing from direct tax to a broader GST, compensation for those adversely affected, and the removal of nuisance taxes like stamp duty. But as we have seen in recent times, tax reform is hard to get done.

Concluding comment

Australia is in far better shape than many comparable countries – public debt, while up, is relatively low; inflationary pressures are weaker here than in the US and Europe; unemployment is very low; and we are politically less polarised and more open to compromise than the US and parts of Europe. After 15 years of policy drift though, declining productivity growth is contributing to falling real wages, high inflation and rising social tensions. This will weigh on investment returns if not adequately addressed. The best way to address these issues is to build a consensus and commitment for reform. Fortunately, the new Federal Government appears to be heading down this path, albeit there is a way to go.