Investment textbooks tell us that value stocks generally outperform growth stocks in periods of rising interest rates and economic slowdowns. However, history tells us that investors who wait for certainty that the market has pivoted from favouring value back to growth are likely to miss the mark.

Value investing – not dead…yet

Value stocks are defined as those whose share prices trade at lower multiples to book value or earnings than the broader market. These are often businesses such as banks, supermarkets and utilities that deliver more dependable, immediate profits – which investors favour in the current environment.

After a decade of underperformance, value stocks made a comeback earlier this year.

Technology companies and other disruptors saw their share prices slump, while ‘boring’ companies with more predictable earnings came into fashion.

The MSCI World Value (USD) index has dropped 11.96%, while the Growth index is down 27.15% this year1.

Why did this happen?

Inflation increases business uncertainty. Firms with more predictable earnings streams become relatively more attractive, which supports value stocks.

In periods when interest rates rise to control inflation, they impact growth stocks in two ways:

- Higher variable debt costs reduce company profits, especially hurting those with already-thin profit margins.

- Higher bond yields increase a company’s equity discount rate which reduces the present value of future earnings and thus its market value. This particularly impacts growth companies whose profits lie further out into the future.

This has led some pundits to tip value stocks to continue to outperform growth as higher interest rates slow the economy. They suggest investors would do well to favour a value strategy until the market starts to show signs of recovery, and only then should a portfolio be rebalanced towards growth stocks.

But the data tells us a different story

This ‘recovery moment’ may arrive some time before the interest rate cycle peaks, because share markets are forward indicators of future economic health. Markets look ahead towards the economic recovery which follows the eventual downward turn in the interest rate cycle.

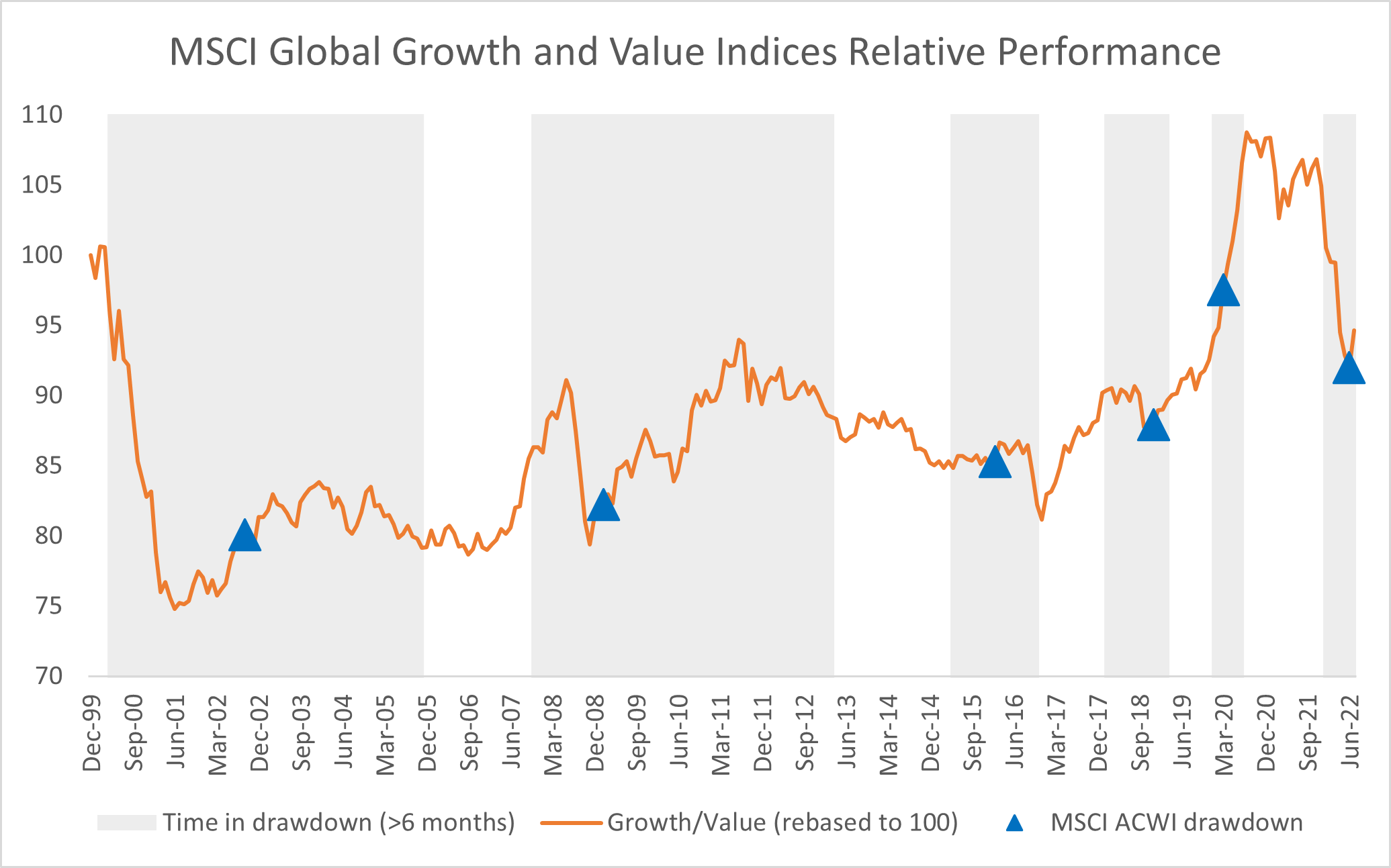

Moreover, the suggestion that growth stocks only begin outperforming value sometime after the maximum drawdown is not supported by historic data. The following chart shows how growth starts to outperform value (i.e. the growth-value relative performance line shifts to sloping upwards) either some time before, or at the point of, maximum market drawdown.

Source: Bloomberg and Pengana

In the tech wreck at the start of the millennium, growth began outperforming value 12 months before the market low in September 2002. Similarly, the February 2009 post-GFC market low was preceded by the start of growth outperforming value by a few months. The COVID market correction bottomed in March 2020, having seen growth outperform value throughout the previous six months.

Market lows and interest rate peaks can only be confirmed in hindsight. However, recent share market history offers little support for ‘waiting until the maximum market drawdown has passed’ before investing in growth companies.

Implications for Investors

All market cycles are unique, and only hindsight will reveal the perfect moment to tilt our portfolios back towards growth stocks.

However, historic data suggests that waiting for certainty that markets have bottomed, and intertest rates are again falling, may mean missing out on periods of strong share market returns. (e.g. The MSCI World Growth Index (USD) outperformed its value equivalent by 5.0% in the 12 months before the September 2002 tech wreck market low, and by 3.49% in the following 12 months.)

Investing in high quality growth companies, with moderate debt levels, has served as a good investment strategy for investors willing to ignore shorter-term market fluctuations. Such a strategy requires investing for the long term and recognising that well managed companies that grow earnings over time can sometimes be poor short-term performers.

1 Year to 16 September 2022