Carbon is a chemical element with the symbol C. In combination with two oxygen atoms it forms carbon dioxide CO2. While CO2 is necessary for life, its concentration in the earth’s atmosphere has increased since the pre-industrial era due to human activities. One way governments and institutions are targeting to reduce the level of CO2 is via a carbon price.

It is important to understand what a carbon price is, and what it is not.

A carbon price defined

In 2019, comedian John Oliver, on his show “Last Week Tonight”, described carbon pricing, saying “we’ve universally agreed polluting is bad, and yet it is free to do it. When you litter you pay a fine, when you drive above the speed limit you pay a fine.” Likewise carbon pricing requires polluters to pay for the CO2 they release into the atmosphere. There are two main forms of carbon pricing:

- Carbon taxes; and

- Cap-and-trade programs.

Carbon pricing threads climate change costs into economic decision-making. It incentivises changes in production and consumption patterns toward decarbonisation. In other words, it makes polluting more expensive and clean energy more affordable following innovation and investment in green solutions.

Carbon taxes and cap and trade schemes

A carbon tax is simply a levy on carbon. The price is set by the government.

A cap-and-trade program (also known as an Emissions Trading Scheme or ETS) allows market participants to buy and sell permits for emissions or credits for reductions in emissions. Emissions trading allows established emission goals to be met in the most cost-effective way by letting the market determine the lowest-cost pollution abatement opportunities. By limiting the supply of carbon credits, the government is putting a cap on total emissions.

Carbon credits are either:

- auctioned by the government and then traded, or

- given free to regulated firms who can then trade them.

These primary and secondary market sales and purchases result in a market price for carbon. In other words, there is a market setting the carbon price.

The intention and workings of an ETS

ETSs are regulated by governments. For example, in the EU Emissions Trading System, governments set the supply of carbon credits or a carbon cap in order to achieve certain emission reduction outcomes.

Each year organisations with a large carbon footprint are allocated an allowance proportionate to their historical emissions.

Polluters will either emit more than their allowance or will emit less than their allowance. These companies will then have to trade with each other through intermediaries to be able to balance out their carbon emissions so they can meet the regulatory cap.

Companies that want to buy carbon allowances, that is those that emitted more than their allowance, will have to pay an explicit price to those companies with excess credits, that is those companies that emitted less than their allowance and can sell them.

The result is that it is more expensive to pollute, unless the means of production is improved to reduce emissions.

The price of carbon is thus determined by supply and demand

In an ETS, the price of carbon is determined by supply and demand. A key characteristic of carbon markets is that supply of credits is controlled and limited, determined by the government at an amount deemed acceptable and in line with its emissions reductions targets.

The cost of credits will rise and fall depending on whether firms find alternatives to polluting.

As supply is constrained and expected to fall over time, the market price of carbon credits is expected to rise, resulting in an increased incentive to emit less. The by-product is a price that is structurally designed to rise over time.

While the emissions trading schemes around the world may differ in size and price per carbon credit. Schemes will generally lower the cap on allowed carbon emissions each year as they move towards net-zero.

By assigning a price for polluting activity, these systems provide an economic incentive for companies to reduce emissions.

The development of compliance carbon markets

The oldest and largest active market is the European Trading System which has been operating since 2005.

There are more than 20 such markets around the world, and analysts expect around 20 more to come online soon, most recently China brought one of its emissions trading schemes online.

The growth of big carbon markets is still in the early stages. For the first time in 2021, emissions trading systems (ETS) generated more revenues than carbon taxes. According to the World Bank. ETSs generated around US$55 billion in 2021.

The total size of the ETS market, according to MSCI, is US$270 billion. Credit Suisse says this figure could reach more than US$1 trillion in the coming years, driven by higher carbon prices and the expansion of emissions coverage, while the trading value could be multiples of that driven by improved accessibility and liquidity.

We believe this space will develop and therein lies the opportunity.

Drivers of the carbon price

The global carbon market has experienced fluctuations over 2022 due to the macro environment and individual market pressures, but opportunity persists particularly as governments accelerate towards net zero by 2050.

Generally, each year governments will reduce the caps, or amount of emissions entities are legally allowed to make, thus reducing the supply of permits on the various markets which should lead to higher prices for carbon.

If companies are unable to meet the regulated emissions caps, particularly as the caps reduce on an annual basis they are going to have to pay a potentially increasing price to purchase more carbon credits or face heavy fines and penalties. This will create demand from companies that continue to pollute.

External factors such as variations in general economic conditions will impact the price. If GDP falls, demand for carbon credits will fall, conversely if GDP is rising there will be more demand for credits.

From time-to-time it may be necessary to revise the rules of the systems, including those governing offsets and market stability mechanisms, which will impact the price of carbon credits.

Carbon as a new investment asset class

Investor interest in carbon markets is growing rapidly. According to the institute of Chartered Financial Accountants (CFA) carbon has exhibited attractive historical returns and a low correlation with other asset classes, making it potentially attractive as part of a diversified portfolio.

Furthermore, because of the design parameters of ETSs including the objective of higher prices and lower emissions, there is a well understood and logical case for a forward-looking risk premium for carbon.

Many experts see carbon as an emerging asset class. In fact, McKinsey says “when we look at the development of carbon markets, what strikes us are the parallels it has with the evolution of other commodity markets, whether its soybeans, pork bellies or natural gas. And, in commodities markets like that, investors and financial institutions really have an important role in providing liquidity, aiding price discovery, matching supply and demand over time, being market markers. Similar to commodity markets we think carbon markets will evolve in pretty much the same way. So it’s about providing these value-added services rather than trading speculatively.”

Credit Suisse goes further saying “carbon is an emerging asset class that could potentially rival the global oil market in size.”

What a carbon price is not: voluntary carbon markets and offsets

You may have read about Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM), because that is what Australia has. Australia’s voluntary market has been the subject of criticism of late for a number or reasons. It’s important to note that VCMs are not ETSs. VCMs are often not regulated by governments (Australian carbon credit units or ACCUs are regulated by the Clean Energy Regulator), and the contracts being traded are called carbon offsets.

It is even possible for individuals to purchase carbon offsets. You may have seen a tick-box on an online order form that allows you to select to offset the carbon for your delivery. Some airlines give you an option to buy a carbon offset for flights.

Carbon offset contracts represent sponsorship of a project that is meant to decrease the amount of carbon being emitted, which serves to offset the emissions. The projects backing these contracts are varied; they range from a reforestation initiaves, to solar farms, or clean cooking stoves.

There are well noted issues surrounding the legitimacy of carbon offsets.

In 2022, John Oliver dedicated a whole episode of Last Week Tonight to carbon offsets, and as he humorously points out in that episode he “doesn’t open this beak to squawk out good news.”

The Financial Times says, “the market is opaque and unregulated, with resellers in the form of middlemen brokers accused of cashing in at the expense of environmental causes.”

McKinsey says “Today’s voluntary market, is fragmented and complex. Some credits have turned out to represent emissions reductions that were questionable at best. Limited pricing data make it challenging for buyers to know whether they are paying a fair price, and for suppliers to manage the risk they take on by financing and working on carbon-reduction projects without knowing how much buyers will ultimately pay for carbon credits.”

Unlike carbon allowances at ETSs, where rules are set by national or international public authorities, the voluntary carbon market does not have any governance body.

The price is not set by any demand or supply factors.

What a carbon price is not: An investment in companies that claim to be carbon neutral

Companies that claim carbon neutrality or working toward net-zero may participate in ETSs or VCMs, but their activities are not likely linked to the price of carbon. This is unlike gold miners or nickel producers, their financial outcomes are inexorably linked to the price of the metal they produce.

In this way it is difficult for investors to access carbon markets.

VanEck is giving investors that opportunity.

VanEck Global Carbon Credits ETF (Synthetic) (XCO2)

XCO2 which launched recently, is an Australian first and an innovative way for Australian investors to potentially benefit from changes to the price of carbon.

XCO2 tracks the ICE Global Carbon Futures Index which is an index made up of carbon prices from the four most actively traded carbon futures markets in the world:

- European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), started in 2005

- Western Climate Initiative (California Cap and Trade Program), started in 2013

- Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), started in 2009

- UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS), started in 2021

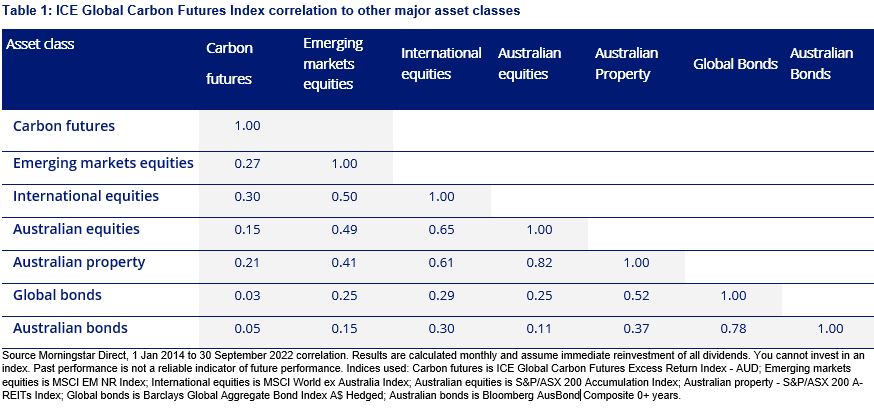

As a diversifier, investors are attracted to carbon credits because of its historically low correlation to other asset classes. The table below shows the correlation of carbon futures compared to other asset classes. In the table, a 1 is perfectly correlated. The lower the number, the lower the correlation.

Key risks

An investment in the ETF carries risks associated with: ASX trading time differences, market risk, concentration risk, futures strategy risk, cap and trade risk, currency risk, political, regulatory and tax risks, fund operations and tracking an index. See the PDS for details.

As always, if you are considering an investment in VanEck Global Carbon Credits ETF (Synthetic), we recommend that you speak to your financial adviser or stock broker.