by Jessica Cairns – Head of ESG & Sustainability

The Australian ESG world was sent into a flurry by changes to the Safeguard Mechanism and Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) that were proposed in January. The Safeguard Mechanism was put in place in 2016 as part of the Emissions Reduction Fund. It essentially set emissions limits (baselines) for high-emitting industrial facilities across Australia and required facilities to buy carbon credits to compensate for any emissions in excess of that baseline. The scheme covers more than 200 individual facilities, each of which emits more than 100 000 tonnes of carbon equivalents per year. These Safeguard Facilities generate almost 30% of Australia’s total emissions between them and many are owned by some of Australia’s biggest listed companies including BHP, Rio Tinto, BlueScope Steel, Santos, Woodside Energy, Orica, and South32.

Last year, when the new Federal Government made a commitment – and legislated – to reduce national emissions 43% by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050, it flagged the need to strengthen the Safeguard Mechanism which would continue to encourage Australia’s largest emitters to reduce emissions. The Government finally released its position paper in January which proposed changes to the scheme. Although many expected this would be the final say on the changes, the Government has committed to one more round of feedback (due 24 February), before final changes will come into force on 1 July 2023.

There are a number of key changes to the scheme which may mean many companies will exceed their baselines at a facility level (at least initially), however, this will be more of an issue for companies which have most of their operations in Australia. The Safeguard Mechanism will have less of an impact on companies like BHP, that operate globally, since the facility level impact will be diluted at the group level.

Changes to the scheme

A few important changes to be aware of:

- Safeguard Mechanism facilities can no longer generate ACCUs: Historically, the scheme allowed companies to generate ACCUs for activities which promote carbon abatement. These ACCUs were then sold to the Government or into the market, and essentially helped fund energy efficiency projects. Now, Safeguard Facilities can no longer generate ACCUs. Safeguard Facilities which reduce emissions below their assigned baselines will instead be allocated Safeguard Mechanism Credits (SMCs) which they can either bank and use later, sell to another safeguard facility, or use to meet a baseline at another of its facilities. Any existing contracts with the Government would still be valid. The paper states that “it doesn’t make sense to allow projects that reduce regulated emissions to generate offsets”. We agree with this statement, and support the overall aim to improve the credibility of ACCUs, however we do have some concerns that introducing another crediting system is going to introduce complexity in pricing and trading.

- Baselines will decrease by 4.9% year-on-year and be set based on industry averages:

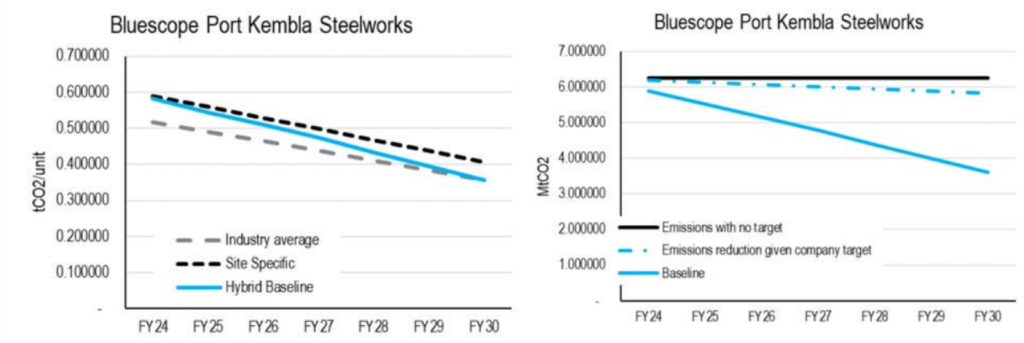

- The Government intends to retain the existing production-adjusted (intensity) baseline framework, which allows baselines to grow and fall with production. However, baselines will now be set using a “hybrid approach”. Initially, baselines will be tilted towards the historical site-specific emissions, but as 2030 approaches baselines will move towards industry averages. Baselines for any new facilities will be set based on international best practice.

- Baselines will reduce 4.9% per annum from the industry average. This means that reductions of more than 4.9% will be required for some companies to meet the baseline if the current emissions are above industry average.

For example, the graph below shows the change to the baselines for Bluescope Steel’s Port Kembla asset. Assuming its production remains largely consistent, there would be a 14% difference between emissions at the facility and the baseline requirements in 2030.

Source: Credit Suisse

- Lots of flexibility in the scheme: Recognising that emissions pathways are rarely linear, the scheme builds in a lot of flexibility so companies will be able to meet their compliance requirements without being unfairly impacted at any particular point. For example, unlimited banking of SMCs would be allowed to 2030. Borrowing of up to 10% of the baseline each year would also be allowed to 2030. Finally, multi-year monitoring periods up to 2030 would be available, whereby a facility that has exceeded its baseline emissions due to a lack of available technology, but has a firm and credible plan in place to reduce cumulative emissions before the end of the five year period, has room to move. There is also a proposed penalty for facilities which don’t meet the compliance requirements, although we believe it is unlikely that this will be imposed on many companies when it will likely be much cheaper just to buy ACCUs or SMCs.

- Trade-exposed industry facilities (known as IETE) can apply for special considerations: 80% of companies under the scheme are considered to be trade exposed. If the cost impact of buying ACCUs/SMCs is more than 3% of revenues at a facility level, these companies can apply for funding support and a baseline adjustment to reduce the pace of baseline decline to 2% instead of 4.9%. The Government has also allocated some funding for these companies to support emissions reduction initiatives.

- ACCUs issued by the Government will be capped at $A75/tonne: This cap does not apply to ACCUs bought and sold in the broader market or to SMCs traded between facilities. For context, at the time of writing, ACCUs cost about half that amount, and their equivalents were trading at ~€85 ($A130) in Europe and ~$US80 ($A110) in California. It is envisaged that these credits would be purchased by Safeguard Facility companies that exceed their baselines and need credits (ACCUs or SMCs) to meet their compliance requirements. This cap will be reviewed in 2026-27. There has been no comment on the pricing structure for SMCs. There has also been no commitment from the Government that it will ensure there will be sufficient ACCUs to service all the facilities which need them. This means it is possible there will be a third pricing structure consideration for companies that buy ACCUs from the wider market, rather than from the Government.

Stock implications

Most companies under this scheme will be impacted in some way. However, we expect that companies with concentrated assets in Australia that are also considered ’hard to abate’ will be most negatively impacted. For example, the following potential impacts for Bluescope (BSL), Adelaide Brighton (ABC) and Woodside (WDS) have been estimated by Credit Suisse:

- BSL would need to reduce its emissions at its Port Kembla steel-making facility by 42% to meet the new 2030 baseline. The potential cumulative cost for carbon credits is $712 million (assuming the company meets its existing climate targets and the price of credits is $75/tCO2e). At 2025, assuming production stays the same, the potential EBITDA impact could be 9.5%.

- ABC would need to reduce its emissions at its Cockburn and Birkenhead cement-making facilities by 28% to meet the new 2030 baselines (Dongara is excluded from this assessment). Assuming a $75/tCO2e carbon price, the potential cumulative cost could be $109 million. At 2025, assuming production stays the same, the potential EBITDA impact could be 10%. The potential cumulative cost to buy carbon credits between now and 2030 is $89m

- WDS would need to reduce its emissions at two facilities by 68% to meet the new 2030 baselines, and there is a potential cumulative cost of $384 million assuming the company meets its existing climate targets and the price of credits is $75/tCO2e. The EBITDA impact in 2025 however is only expected to be 0.3%.

- These companies could all be eligible for the IETE funding/baseline adjustment, however most modelling that we have seen estimates the cost impact would be less than 3% of revenue.

The changes to the ACCU rules could also have potential implications for Santos (STO) and its Carbon Capture and Storage development at Moomba. As far as we are aware, Santos was not able to secure a contract to sell ACCUs to the Government last year which means that under this new rule, it will not be able to sell ACCUs at all. It may be able to generate and sell SMCs instead, however this has not been confirmed.

Companies with ambitious emissions reduction targets and programs in place may benefit from the scheme changes. For example, Credit Suisse has estimated that Fortescue Metals Group (FMG) may be able to generate and sell SMCs between now to 2030 for $129 million (assuming a $75/tonne price consistent with ACCUs) if they meet their stated decarbonisation targets.

Summary

The changes support the Australian Government’s commitment to reduce national emissions by 43% by 2030 however we expect that there will need to be further broad regulatory efforts to reduce Australia’s emissions. A number of elements in the scheme will be reviewed again in 2026/27, including the ACCU price cap and baseline reduction rates.

At a company level, we expect that the cost impact will be most material for companies whose revenue-generating assets are primarily in Australia. Companies with global operations will have a smaller overall impact because the cost to purchase ACCUs or SMCs will be diluted at the group level.

Some companies may also generate SMCs if emissions are below the facility baseline. These companies can then either bank them for later years, use for compliance at other facilities, or sell these SMCs to other companies that need them for compliance.

Although the $75/tonne cap gives some certainty on pricing for Government-held ACCUs, there are still many questions about the price for non-Government held ACCUs and SMCs, and the trading mechanism for SMCs.

At this stage, all of the above changes are proposed and yet to be confirmed. However, given the amount of consultation that has taken place to date, we expect that the reform won’t change materially between now and when it goes live on 1 July 2023.