by Saskia Kort-Chick

Social issues are perhaps the most difficult to research and least understood by investors with an environmental, social and governance (ESG) focus. But the risks and opportunities they represent are growing, and investors need a way to step up to the challenge.

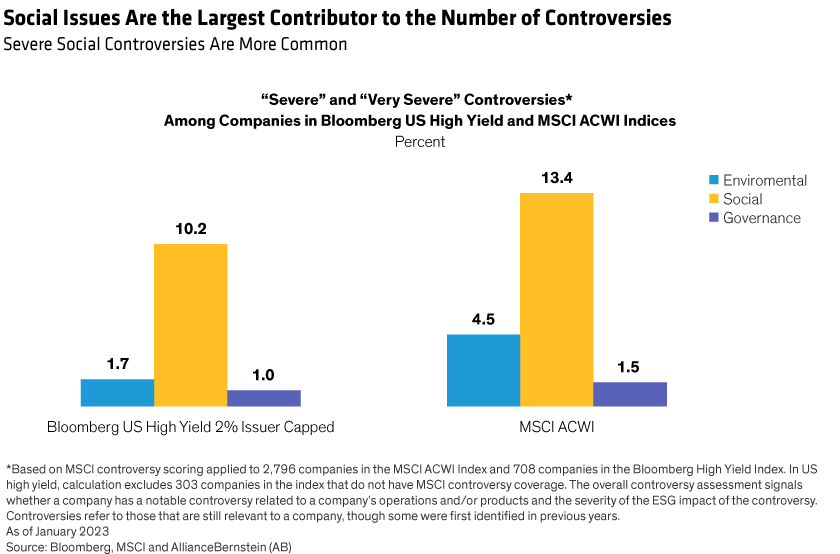

From modern slavery to female representation in the workforce, companies are plagued by a growing list of social concerns. These issues account for a higher proportion of corporate controversies than environmental and governance issues. Yet ESG-focused investors, who have become increasingly systematic and sophisticated in incorporating environmental and governance factors into investment decisions, don’t have similarly robust processes for addressing social factors.

The reason? Data about social factors are relatively scarce, vague and hard to blend easily into a research and investment process. With social trends and new legislation in the spotlight, investors can’t afford to ignore the risks to companies and investment performance.

Investors, in our view, can rise to this challenge—and the opportunities it creates—by understanding how to apply and expand upon the available data within a research framework that captures three critical dimensions of global social change.

Why Social Data Lags

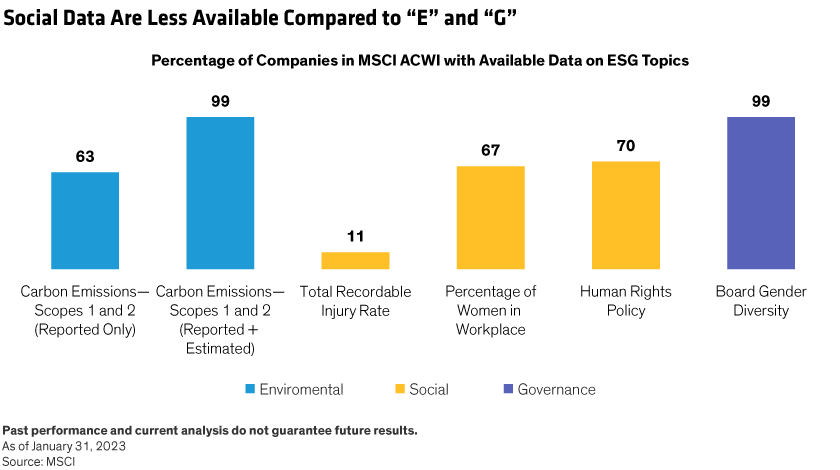

Tighter regulation and quasi-government scrutiny of “E” and “G” issues have prompted dramatic data improvements in these areas. Now, official interest in social issues is increasing. This may help redress the information imbalance, in which the availability of data for social factors remains relatively low compared to “E” and “G”.

The most commonly available social data concern workforce gender diversity, health and safety, product recalls, and human rights policies. But data quality remains sketchy. For example, the fact that a company has a human rights policy doesn’t mean it is a good policy or well implemented.

It’s also difficult to compare social metrics across companies and industries. Unlike carbon footprints and governance standards, which can be easily compared across companies or sectors, social issues differ across industries.

In the apparel industry, for example, key issues include forced or child labor, the proportion of employees covered by trade unions or bargaining agreements, grievance reporting mechanisms, and supplier codes of conduct.

In retail banking, predatory lending is a big social concern, along with access to services for customers from lower-income backgrounds, privacy and data security, and fines levied for regulatory breaches. Food and beverage companies should be judged on product quality and recalls, investment in safety and quality systems, and production time lost because of workplace injury or safety incidents.

These issues will gain more prominence because official scrutiny of “S” factors is increasing steadily.

Investors Face a Tsunami of “S”-Related Legislation

Our research shows that, between 2011 and 2022, key Western governments and quasi-governments took 23 significant actions—such as introducing legislation or guiding principles and holding parliamentary inquiries—to curb forced labor and human rights abuses. Most actions (17) took place in the second half of that period.

This slow-moving tsunami of legislation will force companies to carry out and report due diligence in their operations and supply chains. Government moves to ban products made with forced labor are already underway in the US and will soon be followed by the European Union.

Grassroots awareness of social issues is becoming more vocal. COVID-19 highlighted the inequality of vaccine distribution and the strain on healthcare, while supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic and by the war in Ukraine have shed light on challenging conditions in some export-producing countries. Rising inflation and the cost-of-living crisis are increasing public awareness of social issues.

Investors, in our view, should take two steps to accommodate the growing importance of “S” factors in their portfolios.

Data Science and Qualitative Analysis Can Drive Insights

The first is to address issues of data quality and availability. Where data are available, their materiality for various industries should be mapped appropriately. Then, data science and qualitative analysis can help drive better insights.

For example, specialized third-party providers may have more in-depth knowledge of “S” factors than in-house securities analysts, but they typically cover fewer companies. Using data science, investors can access new data sources with the help of artificial intelligence.

Understanding the data is important to avoid drawing false conclusions. “S” controversies are more common in some industries, such as autos. But don’t assume that industries with less data have a correspondingly low level of controversies. Similarly, fundamental research can verify that a company’s human rights policy is effective and appropriately implemented.

Three Dimensions to Understanding “S” Issues

The second step is to develop a research framework that can identify key “S”-related risks and opportunities.

We have identified three broad themes to help investors make sense of the evolving “S” investment environment: a changing world, a just world and a healthy world.

These themes cover multiple and far-reaching changes. From a changing world perspective, for example, they include understanding how human capital management can give firms a competitive advantage, the implications of an aging workforce and the risk that 30% of jobs could be lost to automation by 2030.

Thinking about the world in social justice terms can focus investors on growing evidence of a positive correlation between female corporate leadership and corporate performance. It can also alert them to industry-wide costs of import bans on products made with forced labor.

The global transition to a low-carbon economy puts pressure on governments to develop policies to help people adapt as old jobs are lost and new ones created; how well governments perform in this respect will have implications for sovereign-bond investors.

Health is also important for companies and investors. In fact, poor health is estimated to cost the world US$12 trillion a year—equivalent to about 15% of annual global GDP. 1

Avoiding a Rock and a Hard Place

Companies and investors are under increasing pressure from governments and the public to identify and take responsibility for social issues that arise in their business operations and investment portfolios.

Given the data issues, some investors may feel they are wedged between a rock and a hard place. That pressure can be eased, in our view, by capturing and collating the available data, wringing better insights from them with data science and qualitative analysis, and applying those insights through a comprehensive research framework.

Saskia Kort-Chick is Director of ESG Research and Engagement—Responsible Investing at AB

Roxanne Low, ESG Associate from AB’s Responsible Investing team, contributed to this analysis.

1 Jaana Remes et al., “Prioritizing Health: A Prescription for Prosperity,” July 8, 2020, McKinsey.com