by Julian Howard – Lead Investment Director, Multi-Asset

In Central Asian folklore, the rascal Khodzha promises the Emir in exchange for 1,000 coins that in 20 years he will have taught his donkey to talk. Of course he knew very well that in 20 years, either the Emir or the donkey would be dead, enabling him to make such a bold claim free from any fear of reprisals. Equity investors too are often made very long-term promises about the potential returns from equities by professional managers, except in place of cynicism there is the hard evidence of history and the intuitively logical potential for listed corporations to grow over time.

That evidence is arguably best personified in two major studies of asset returns over time. The first is the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (NBER) ‘The Rate of Return on Everything 1870-2015’ published in 2017 which, as the name suggests, explores long term returns across equities, fixed income and real estate. The second is Jeremy Siegel’s regularly updated ‘Stocks for the Long Run’ which has become the Old Testament of buy-and-hold investing. The conclusions of both are remarkably similar – that over a multi-decade period the real return on equities has historically been around 6.5-7%.

Detractors would point to the current era of volatility as a reason why such a return may not be replicated in the future. The recent Covid-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the ensuing inflation spike and rising interest rates in response, as well as a new banking crisis make a smoothly-delivered 7% annual real return feel like a very distant prospect. But all of this, and much worse, has been seen before within living memory and is included in the 6.5-7% figure quoted. The case for a structural allocation to stocks therefore remains undimmed, in our view. It also makes intuitive sense when one considers that many of the greatest human innovations are packaged, delivered and ultimately monetised by the corporate entity. From the mass manufacture of the Model-T Ford in the 20th century to the introduction of artificial intelligence into our search engines, listed companies can be reasonably expected to continue to play a central role in advancing human progress, thus generating ongoing returns for their shareholders. This renders vital a structural allocation to stocks in nearly all long term portfolio solutions.

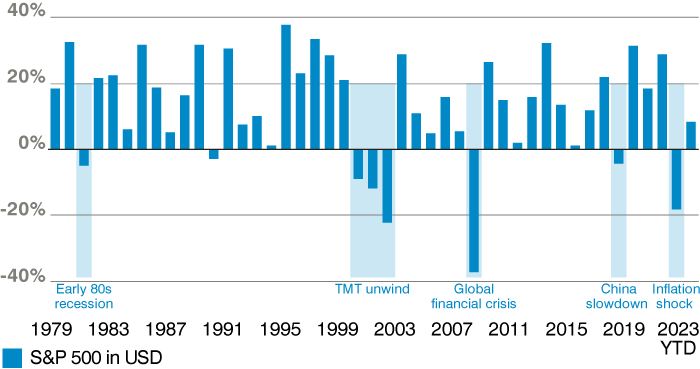

That is the ‘easy’ part. The challenge is when a time horizon is introduced that demands at some definite point in the future that funds be made available. For individuals this may be a retirement date, for institutions perhaps a funding requirement for a planned project. Such a specifically-defined ‘landing zone’ is at odds with the concept of indefinite buy-and-hold simply because there can be entire years or longer in which markets underperform. The dot-com unwind from 2001-2003, the global financial crisis from 2007 to 2009 and more recently of course the post-pandemic inflation shock of 2022 are among the more notable recent examples. Times like this are clearly not ideal for selling, yet planned (and indeed unplanned) liabilities can often fall due at such inconvenient moments.

Chart 1: Not a linear delivery process – stocks can and do pause for years

The portfolio construction response to this lies in ironing out the downdrafts of a stock-dominant portfolio without excessively holding back upside potential. Such a perfect asymmetry is hard to come by but a well-diversified sleeve of assets focused on capital preservation can get much of the way there. The investment universe supplies, among others, two key means of doing this, both of which are worthy of investigation. First is fixed income and credit, or bonds, which can accrue a steady income with varying degrees of capital stability. The second is alternative investments which, as the name suggests, can potentially generate returns independent of the stock market. Both approaches are fraught with practical difficulties. Wringing out a good yield from bonds usually demands some combination of risk-taking in the form of time, default potential or esoteric complexity. In alternative investments, the HFRX Hedge Fund and Macro CTA peer group indices in USD have delivered lacklustre compound annual returns of 1.5% and 0.7%, respectively, over the last decade to 13 April, despite premium fees and being home to some (but apparently not all) of the brightest investment talent. Of course, it would be absurd to ignore the significant role fundamental research plays in identifying effective instruments and funds within both asset classes. But a glance at the performance of the Lipper Flexible Global peer group suggests that consistency in multi-asset portfolios holding more than just equities remains a general challenge.

Today, there is a real-world solution to this problem in the form of short-dated fixed income instruments issued by the Treasuries of the US, UK and eurozone. Such cash and near-cash instruments have directly benefited from rising interest rates in those respective economies. Focusing on the US, the 6m US T-Bill now offers a cool 4.7% nominal yield, far in excess of the 10-year annualised return from the HFR Hedge Fund index quoted above, and with near-instant liquidity. This return is also essentially risk-free unless one feels the US Treasury is about to default on its obligations. Admittedly, it is still just below the 5% rate of US headline inflation, and thus represents a negative real return, but beating inflation consistently is arguably best covered by long term investment in stocks that can exert pricing power over time. For the portion of a portfolio designed to protect nominal capital and smooth out the delivery of returns, the US Treasury bill and to a lesser degree its UK and European equivalents, are almost unbeatable capital preservation assets.

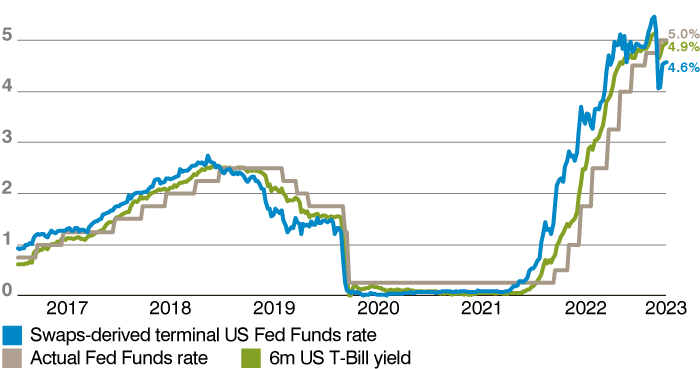

But as the anti-hero Khodzha knew, nothing lasts forever and the real issue with riding short-dated fixed income instruments is that at some point monetary policy in the major economies will peak and start to ease off again, thus reducing the risk-free yields on offer. Here investors can be somewhat reassured that, in the US at least, market participants have consistently underestimated the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) resolve to defeat inflation. Even amid the recent banking issues and a decelerating headline inflation picture, it remains determined to keep tightening policy. Inflation, after all, remains way above its 2% target while unemployment is low, prompting the Fed’s rate-setting committee in the minutes of their March meeting released in mid-April to remark that “Some additional policy firming may be appropriate.” At some point of course, inflation will drop down to the Fed’s target and the central bank will be able to pause and then lower rates. But for now investors, especially in USD, still have time to ‘lean in’ to short-dated fixed interest instruments as an effective nominal capital preservation tool.

Chart 2: Market continues to underestimate Fed’s resolve

Constructing truly suitable portfolios for investors requires the marrying of two concepts to produce practical, real-world outcomes. The significant potential of equities is best unlocked over a multi-year period but smoothing out the characteristic volatility to better meet future funding requirements demands a consistency from capital preservation that has proven frustratingly elusive in recorded outcomes. The very word ‘cash’ has (unjust) connotations of defeat in some dogmatic investment circles but short-dated fixed income, as it should be termed, can periodically offer a near-total solution to the capital preservation issue, even if it is a temporary one. Now is the time to be flexible and pragmatic.