by Garrett Strum – Portfolio Manager | Money Market Analyst and Jim Cielinski, CFA – Global Head of Fixed Income

Concern is mounting in financial markets about the looming debt ceiling. The United States has now met its statutory debt limit of $31.4 trillion. Without an act of Congress, the U.S. Treasury will lose its ability to borrow and will run out of money in the coming weeks. Default on U.S. Treasury bonds or bills, the very definition of a risk-free asset, is almost unthinkable. The ramifications would be far and wide and would likely upend risky assets of all types.

This risk of an actual default is extremely remote. As a tail risk, however, small changes in the narrative can move markets. An increase in default probability from 0.2% to 5.0%, for example, would send shock waves through many parts of the market.

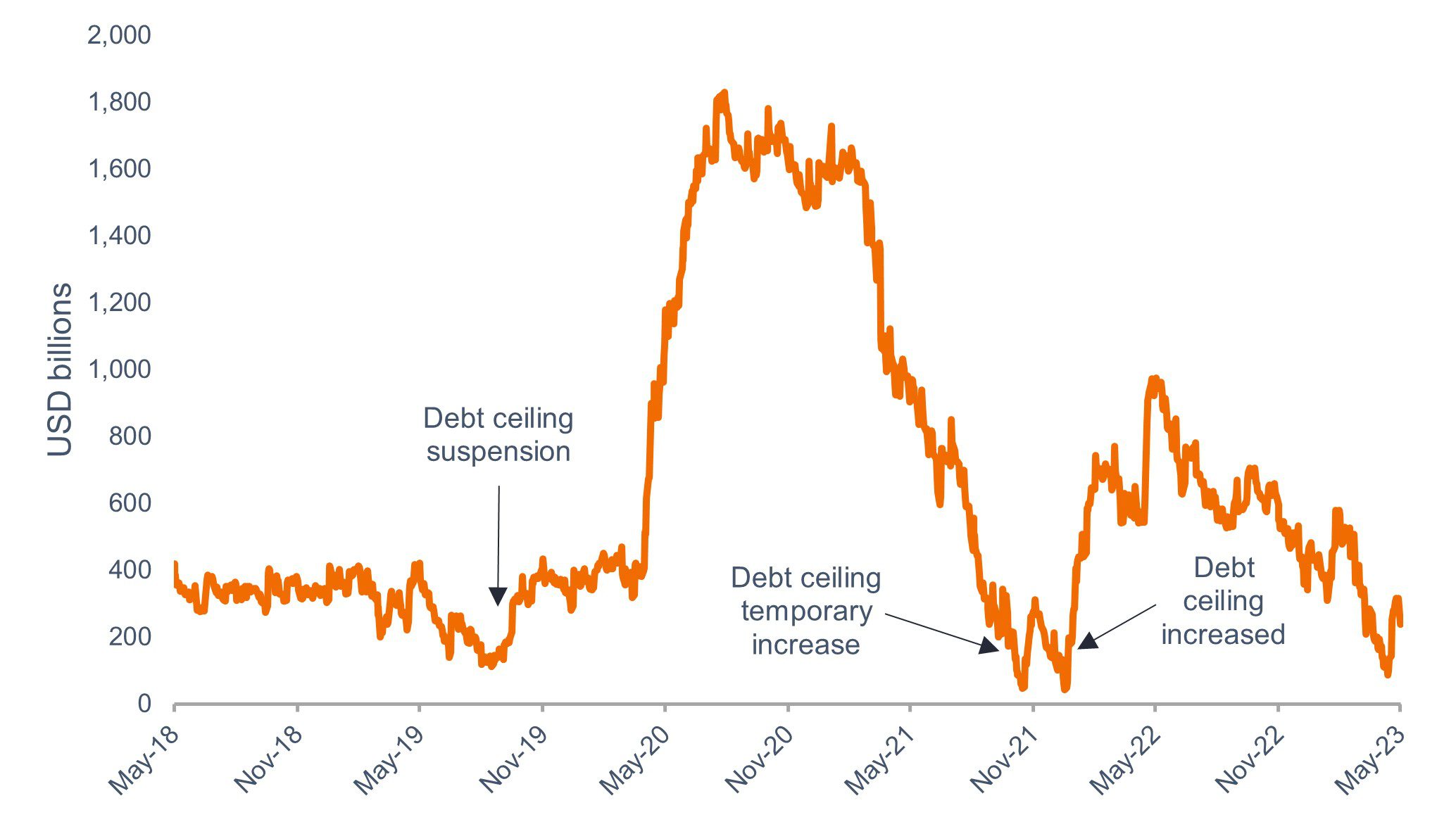

We expect the playbook from previous debt ceiling battles to play out here: Negotiations will go to the wire, but the crisis will be averted at the last moment, if only through one or more temporary agreements. There is no incentive for either side to blink too early. The narrowly split House and Senate provide the ingredients for this to be one of the more brutal fights since 2011, which led to a downgrade of the U.S. debt rating. As shown in Figure 1, political jostling around the U.S. debt ceiling has become commonplace.

Figure 1: Here we go again … U.S. Treasury’s cash balance at the Federal Reserve

Source: FiscalData.Treasury.gov, as of 3 May 2023.

Source: FiscalData.Treasury.gov, as of 3 May 2023.

What paths are available?

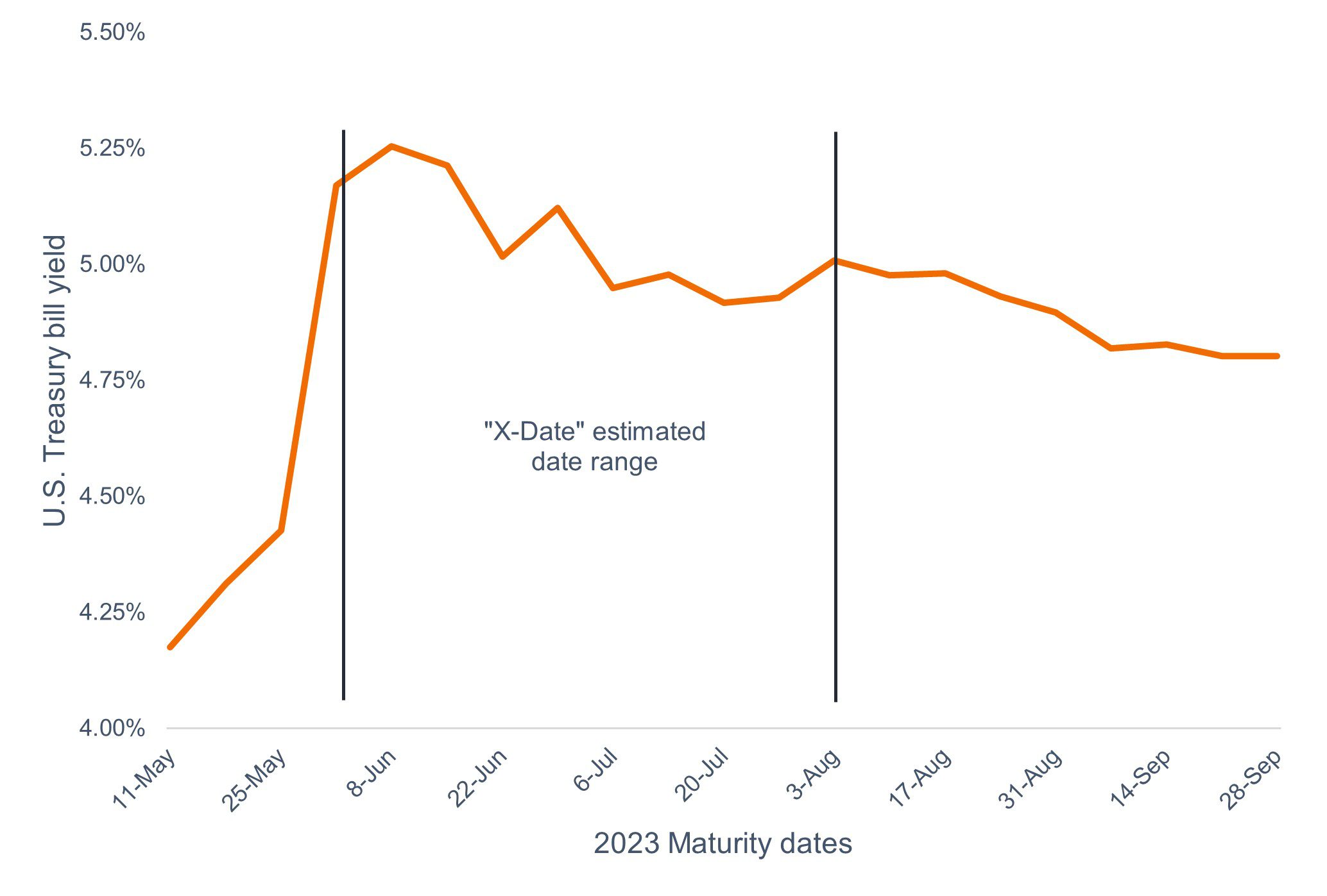

There has been a focus on the “X-Date,” the day where the Treasury exhausts its cash reserves and can no longer honor its obligations. Most estimates suggest this may happen in July or August, although it could be earlier, as indicated by Janet Yellen’s most recent forecast signaling the potential for an early June date. As shown in Figure 2, the potential X-Date window spans a relatively wide short-term maturity window, and investors are demanding a sizeable yield premium to hold securities maturing just after the anticipated X-Date.

Figure 2: Treasury bill yield curve

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as of 3 May 2023.

Resolution will depend heavily on who is taking the blame for the chaos. The public will view default as a byproduct of incompetence. The first rule of politics is that it’s fine if the opposition looks incompetent – but not if it’s you! Thus, the battle in the coming days will center on ensuring the other side takes the blame.

Several outcomes may unfold as we approach the X-Date. One, both parties may simply agree to a short-term extension of the borrowing limit, kicking the can down the road as was done in October of 2021. Two, either party may blink and seek compromise, although such a path would be difficult as House Speaker McCarthy would struggle to get the more extreme elements of his party to agree. Democrats would find a compromise slightly more plausible, but it would be perceived as a sign of weakness.

Importantly, even with a breach of the X-Date, a default on debt can and will be forestalled. The Treasury might attempt to prioritize interest and principal repayments, although this is viewed as operationally difficult. Other obligations – such as pensions and federal payrolls – could be suspended. A full-scale government shutdown would likely ensue, and the public would quickly turn on Congress.

The worst case

What about an actual default? If all else fails, the Treasury might miss some maturity and coupon payments, and market chaos would unfold. This would likely be short-lived, however, as the volatility would prompt a resolution within days, and likely before any technical “default cure” periods expired (i.e., fewer than three days). Even in these cases, debt holders would be highly confident of being “made whole.” No losses would be realized, even though the road would be very bumpy. The Federal Reserve would have a range of untested strategies at its disposal, such as repurchasing defaulted bonds at full value, mammoth short-term repo facilities, and the acceptance of defaulted securities in its money market liquidity facilities. And it would use all of them – probably even a few that are not yet vetted.

Conclusion

An outright default on Treasury debt remains less than a 1% probability. As an important tail risk, it would have pronounced effects on markets were it to occur, but those consequences would likely fade quickly as a resolution would be swift. This explains why early signs of volatility have been confined to short-term markets, where money market investors are loathe to hold delayed or defaulted maturities; Treasury bill yields have been elevated in the June-to-August maturity range, with largely benign movements elsewhere.

We have learned much over the past several debt-ceiling battles. Volatility may be pervasive through the final hours of this reckless game of chicken, but common sense – if not good governance – should ultimately prevail.

DEFINITIONS

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due.

Repurchase (repo) facility an entity that enables eligible firms, who are mainly large banks, to quickly convert their Treasuries into short-term cash loans.

Yield: The level of income on a security, typically expressed as a percentage rate.

Yield curve is a graph that plots the yields of similar quality bonds against their maturities. In a normal/upward sloping yield curve, longer-maturity bond yields are higher than shorter-dated or front-end bond yields. For an inverted yield curve, the reverse is true.

Volatility: The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index, moves up and down. If the price swings up and down with large movements, it has high volatility. If the price moves more slowly and to a lesser extent, it has lower volatility. It is used as a measure of the riskiness of an investment.