by Robert M. Almeida – Global Investment Strategist / PM

Financial markets are sending mixed signals. The US Treasury market, inverted at every standard point, is signaling the material risk of recession while the performance of the equity market points to only a slight pause in growth. At the same time, leading indicators such as tightening corporate lending standards, rising bankruptcies and falling housing suggest that economic and financial stress is increasing. How can investors make sense of it all?

Leading economic indicators can turn out to be coincidental and can flash false negatives. Also, we shouldn’t forget Goodhart’s Law, which posits that when everyone’s watching the same indicator, it tends to lose its predictive power. Since I’m not an economist, I’ll instead focus on the equity market’s complacency and why investors should be concerned.

Ultimately, the only thing equity investors care about is future profits. To arrive at their profit expectations, they incorporate assumptions about the economy, capital costs, tax rates, production costs, pricing power and dozens of other macro and fundamental factors. The weight investors place on these inputs varies by investor and company type since some matter more and some less depending on the circumstances, and some inputs don’t matter at all. Taken together, they funnel down to a single output: earnings expectations.

Exhibit 1 illustrates forward earnings expectations for the S&P 500 Index overlayed with market drawdowns. Despite cautionary signals from the economy or the bond market in advance of most recessions, equities tend to wait until recession risk is looming before pricing in weakness. The equity market typically falls into a deep sleep late in the cycle and wakes up long after other markets, albeit with a jolt.

Thesis creep

A common equity market dynamic late in the cycle is investors filtering out information that runs counter to their bullish investment thesis. In such circumstances, what may have started out as an investment turns into speculation as the hope for financial gain causes investors to ignore the accumulation of worrisome data points.

One data point currently being filtered out is the impact of rising capital costs. Interest rates reflect time preference, or the extent to which people value current versus future consumption. For savers, it’s the reward for forgoing consumption. For borrowers it reflects the preference for current consumption. The rewards for savers and price for borrowers vaulted higher in 2022 and may go higher still. Regardless, what matters now is how funding costs, a financially material input, will affect future profits.

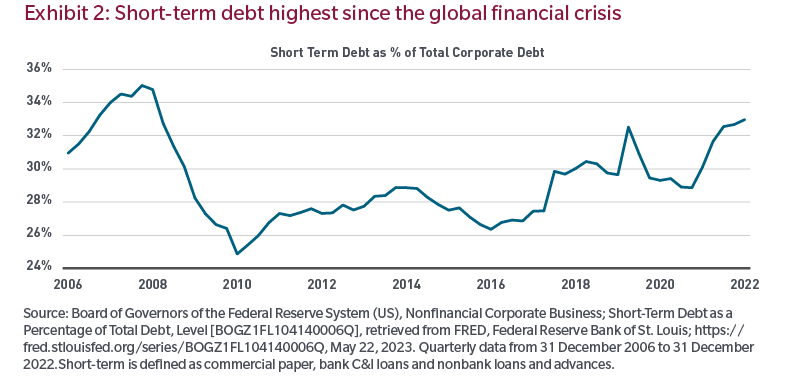

Exhibit 2 may help put this into context. Approximately $1 out of every $3 of US corporate debt is short-term, the highest percentage since the lead-up to the global financial crisis.

A rebuttal to our concern over the significant buildup of corporate debt is that leverage ratios look reasonable compared to trailing profits. But we don’t think that’s the best way to look at it, particularly late in the business cycle. Recent profits were abnormally high due to COVID stimulus, suppressed interest rates and a boost from economies reopening in the wake of the pandemic, all of which have faded. In our view, what will matter isn’t what leverage ratios are today but what they’ll be when profits are stressed.

In 2006 and 2007, MFS fixed income analysts made sure our equity analysts were incorporating higher borrowing costs and stressing their cash flow models. Those preparations benefited many of our equity strategies versus their benchmarks. While conditions are different today, it’s still probably a good time for investors to stress their models again.