by Kanish Chugh

Lesson #1. Gold does well in crises, acting like portfolio insurance

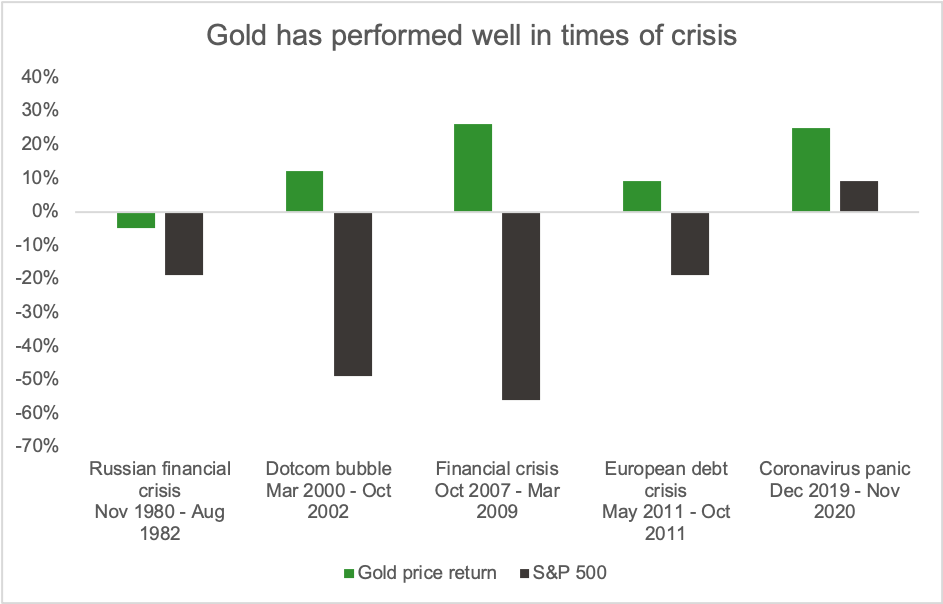

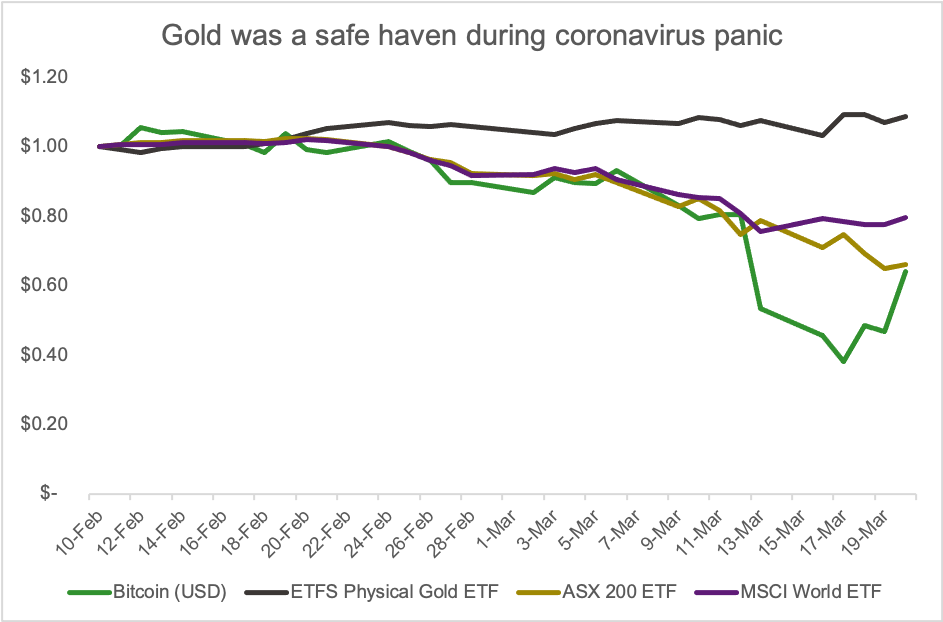

Every investor wants an asset that offers downside protection, or insurance of a sort. And preferably one that is not suspiciously complicated or synthetic. Perhaps the major lesson from the coronavirus is that gold can provide this type of insurance as gold historically does well during collapsing equity markets, as the chart below illustrates.

Source: Bloomberg, ETF Securities, 1 March 2021

Source: Bloomberg, ETF Securities, 1 March 2021

The onset of the coronavirus crisis is generally dated from 31 December 2019, when the virus was first officially reported by Wuhan health authorities in China. The worst of things for markets ended on 18 November 2020, when Pfizer and BioNTech published phase 3 trial results for their vaccine candidate (suggesting that a mass vaccination drive was possible.) Throughout this period, gold provided a return of 25%, compared to the 9% delivered by the S&P 500 in US dollars.

Nothing comes for free of course. And gold can underperform during strong equity market bull runs; such as the dotcom boom of the 1990s. However, this is often the way with insurance policies: when times are good, they fall in price, leaving investors mulling over whether they need them at all. Yet when bad times return, as they inevitably do, policy holders can be glad that they kept them.

Lesson #2. Gold has outperformed most asset classes long-term

The market is a noisy place. And getting caught up in the daily sound, it is easy to lose sight of the long-term picture. For gold, there are two ways of looking at the big picture. First, its long-term returns. Second, the impact that a small allocation can have on a portfolio.

The pandemic has highlighted both benefits gold can bring.

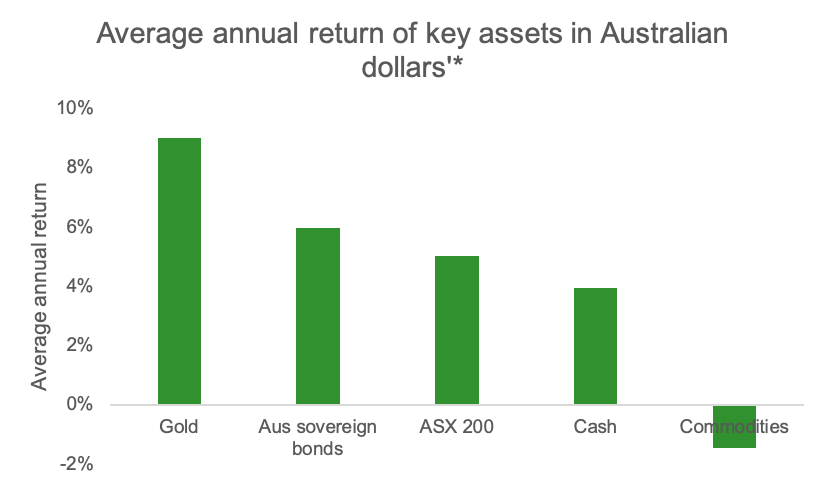

The long-term performance of gold is something that can surprise investors, as received wisdom suggests that Aussie equities outperform other assets over the long term. However, for the two decades leading up to January 2021, gold has been the top performing of the major asset classes. Gold’s outperformance was accentuated by the pandemic, as the ASX 200 is yet to re-achieve its pre-pandemic peak.

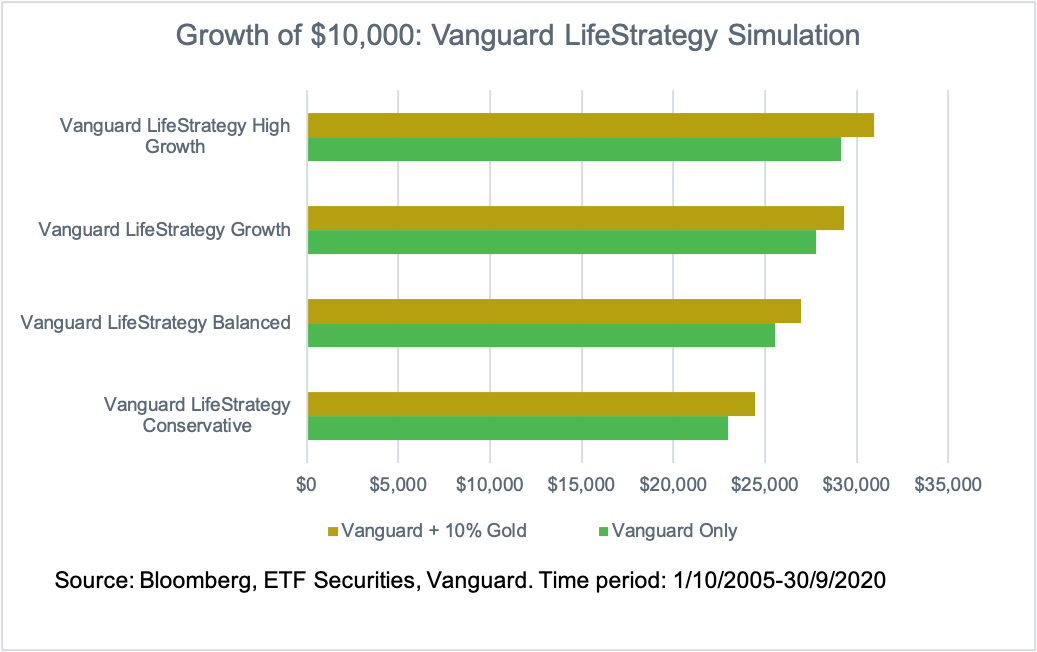

Gold’s ability to enhance portfolio’s risk-adjusted returns was also on display. As gold maintains a low correlation with shares and bonds, it can improve the overall returns of a portfolio. (“Push out the efficient frontier” in the jargon). This can be seen below, with some simulations we have run with Vanguard’s famous LifeStrategy funds. It can be seen that the portfolio with a small gold holding does better on almost every measure. Investors are welcome to try their own simulations, with a small allocation to gold.

Lesson #3. The gold price is driven by negative real yields

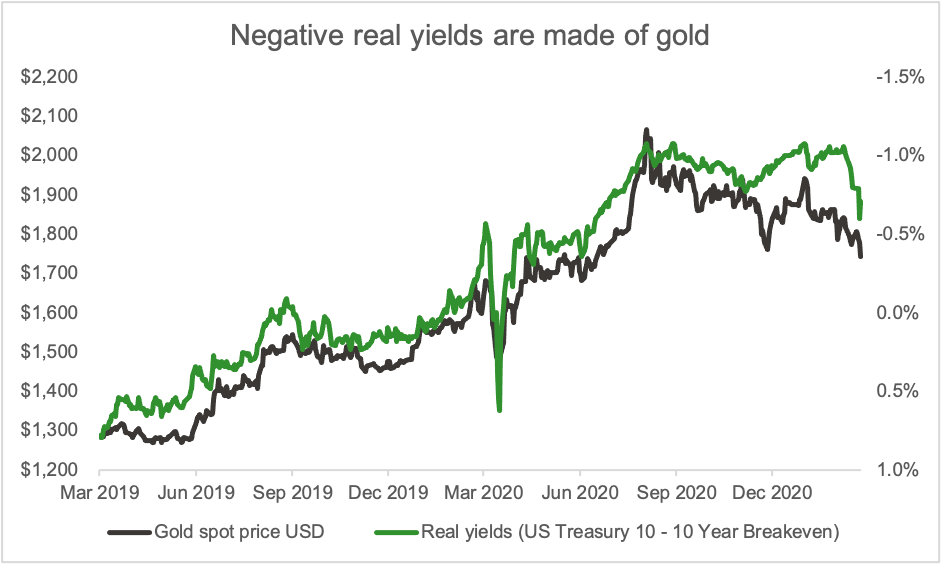

The gold price correlates with the real yield on the 10-year US treasury, the pandemic has shown. Meaning investors who want a signal on the gold price’s future direction potentially have one.

It makes sense that gold would correlate with real yields. As gold provides no income, it can become more appealing when bonds do not have a real income either. And when bonds provide a negative income – meaning bonds are mathematically guaranteed to lose value if held to maturity – it is logical to expect gold to be more appealing still.

Source: Federal Reserve; ETF Securities, 1 March 2021

Aiding golds tether to real yields has been the rise of ETFs, which have allowed more flexibility about how gold is used in portfolios. Prior to 2006, gold did not correlate with real yields. The correlation only emerged after the mainstreaming of gold ETFs in the early and mid-2000s.

That gold ETFs should have this influence has caused some to raise an alarm. Campbell Harvey, professor of international business at Duke University, argues that gold ETFs driving the gold market could create larger drawdowns in the price of gold. He wrote:

“The ETF financialization of gold ownership, in which the real price of gold may be correlated with the amount of gold held by gold-owning ETFs, could possibly lead to higher peaks and lower troughs for the real price of gold relative to the experience of the past.”

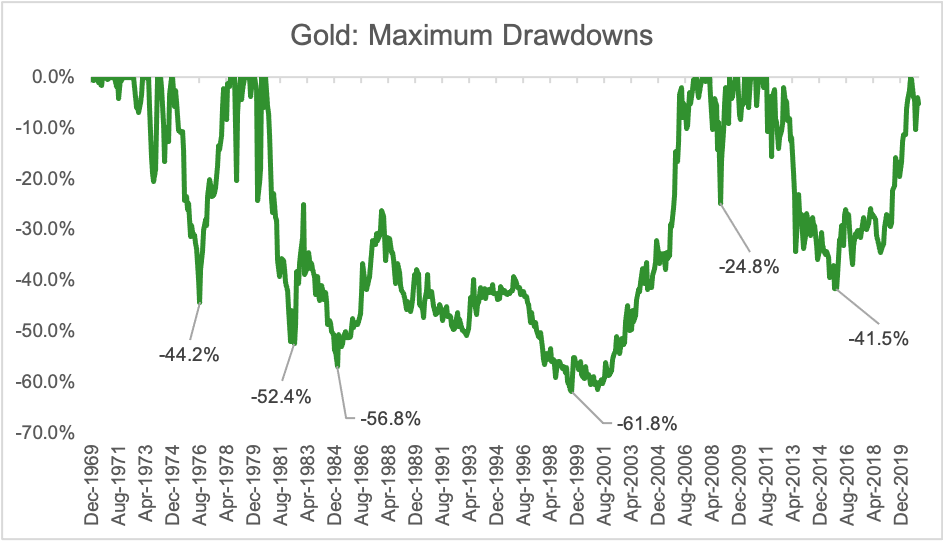

From where we sit, the evidence suggests that the opposite is at least equally possible. Drawdowns in the gold price were larger in the 1980s and 1990s – prior to gold ETFs. What is more, it is hard to see how gold is different from some pockets of the bond market, such as local government bonds, where demand for ETFs can also set prices. This was in evidence in the March 2020 where bond ETFs provided price discovery on untradeable municipal bonds.

Nonetheless, if gold ETFs are part of the reason that gold follow real yields, and gold ETFs are also here to stay – then it follows that the relationship should be robust. And for investors wanting clues on the gold price: watch real yields on the 10 year.

Lesson #4. Bitcoin is not the new gold

Gold and bitcoin are sometimes lumped together – given their apparently limited supply and potential use as alternative currencies. Some analysts have taken the inverse flows between gold and bitcoin ETFs the past several months – gold has seen outflows at the same time bitcoin has seen inflows – as evidence of gold investors migrating to bitcoin.

However, gold and bitcoin are very different, as the pandemic has shown.

|

Past two years |

Volatility |

% of weekly returns lower than -2.5% |

95% VaR per US$10,000 |

|

Bitcoin |

9.9% |

26.9% |

$1,382 |

|

Nasdaq |

3.2% |

8.7% |

$382 |

|

S&P500 |

3.3% |

8.7% |

$306 |

|

Gold |

2.2% |

7.7% |

$291 |

Source: World Gold Council; ETF Securities, 1 March 2021

The most obvious difference has been their volatility—which hit fresh extremes in 2020. Gold for its part was far less volatile than equities throughout the most volatile trading days in February and March. As panic selling peaked, our gold ETF traded sideways, not sustaining any loss of value.

The ASX 200, as measured by an ETF, fell quite significantly. So too, did the MSCI World. But bitcoin was another matter entirely. It dropped more than 50% in the panic in US dollar terms—in keeping with its reputation as a highly volatile asset. Bitcoin and gold behaved very differently.

Source: Coindesk; Bloomberg; ETF Securities, 1 March 2021

The second is that the sources for demand for gold are very different. Bitcoin’s use case is quite narrow, with most end demand coming from speculators. By contrast, most demand for gold comes from central banks and industry, according to the World Gold Council. Investment makes up a significant fraction of demand, but still a minority. This then feeds back into volatility: more diverse demand ensures that gold is, again, less volatile.

Lesson #5. Tactically trading gold has risks

While the gold price has crept steadily upwards over the past 50 years, the precious metal has had periods of sustained drawdowns. This cyclicality might suggest that gold should be traded tactically. In this way, some of the downtrend can be missed.

However, the lesson from our own gold ETF throughout the pandemic is that tactical gold trading has risks. From 17 August 2018 – 6 August 2020 GOLD produced a return of 76% for those who stayed fully invested. But for those who missed the best 10 days in that two-year period, the return GOLD produced was just 29%.

The consequences of missing the best days are not unique to gold. Burton Malkiel, Princeton professor and author of best seller A Random Walk Down Wall St, notes the same thing occurs in the share market. He takes it as evidence in favour of buying and holding an index fund. He wrote:

“Buy and hold investors in the US stock market made an average annual return of 8% during the 15 years from 1995 through 2009. But if they had missed the 30 best days in the market over that period, their return would have been negative [1].”

To be sure, tactical trading may also help avoid the worst days, which can then produce a better return. But knowing whether tomorrow will be a best or worst day is impossible. As we all know, no-one has a crystal ball.

ENDPOINTS

[1] https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703848204575608623469465624