Regular readers will know that since the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have focused on the role of ‘money printing’ in funding government rescue packages and the potential for this to flow through to inflation in goods and services. Our concern has been that a surprising outcome in inflation would threaten the low interest rate environment, which has been a major factor underpinning the worldwide bull market in asset prices. The last six month-period has been interesting as we moved from there being no evidence of inflation, to nascent signs, and now some of the highest rates of inflation, at least in the major economies, that we have seen in decades.

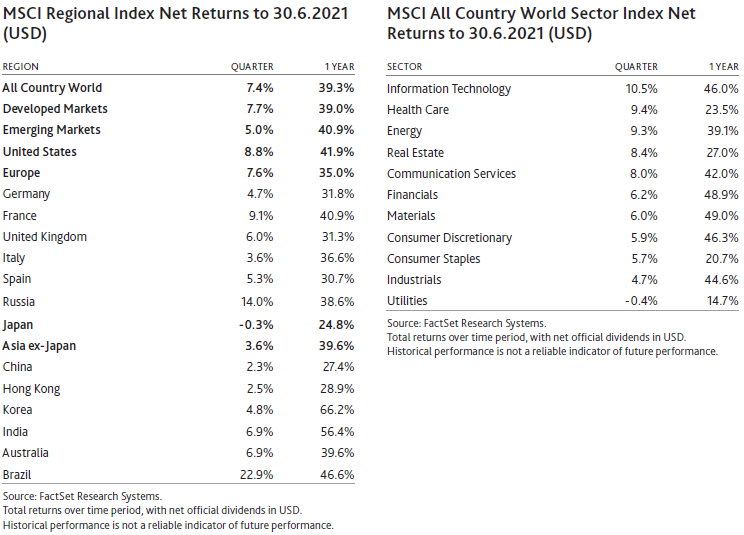

Meanwhile, on other fronts, the relationship between the US (and the developed world) and China, on face value, continues to deteriorate. Attempts by governments around the world to rein in fast-growing monopolies in e-commerce and related areas continue. We are also seeing waves of COVID-19 variants continuing to spread across the globe. Yet, despite these developments, equity markets have broadly moved higher this year, with most markets at, or near, record highs. These share price moves mean valuations remain somewhere between stretched to speculative for much of the market. Admittedly, there has been some nervousness around bond yields, interest rates and inflation at various points along the way, however, by and large, markets have remained bullish. Of course, the positive news has been the very strong economic recovery in regions that are moving steadily toward a post-COVID era.

Making predictions on economic variables is fraught with danger. However, the risk for markets with respect to inflation and the direction of interest rates is unlikely to be symmetric. If the inflationary spike turns out to be short-lived and interest rate rises remain a distant possibility, then the market can likely continue along the same path with valuations remaining elevated for the moment. However, the alternative scenario of persistent inflation that results in much earlier-than-expected interest rate increases by central banks is likely to result in dramatic falls in share prices, especially for the highly valued growth stocks. We would continue to argue, that in this environment, investors should remain cautiously positioned.

Inflation – a temporary blip or here to stay?

The US economy continues to power out of the COVID-induced recession. This is happening, even as unemployment benefits and other government transfer payments are progressively being wound back across the country. Employment growth, higher wages and a drawdown on the extraordinary level of savings stashed away last year are more than offsetting the cutbacks in government spending. In Europe, the economy is steadily making progress, even if at a slower pace than the US, and the Chinese economy is strong enough that the government is focused once again on slowing credit growth and reducing leverage across the economy. While growth rates will fall naturally as the year progresses and comparisons are no longer made against the trough of the recession, we do expect that, absent any other shock, global economic growth will remain robust as such momentum in the economy does not dissipate quickly.

This strong recovery, together with the fact that large service industries, such as travel, are still being impacted by COVID-related restrictions, has resulted in a surprising boom in demand for manufactured goods. This strong demand, together with supply chain disruptions in the early stages of the pandemic, has caused a wide range of commodities and manufactured goods, from copper to semiconductors and new homes, to be in short supply. This has resulted in rising prices for many goods and a spike in the consumer price index (CPI) to an annual rate of 5% in the US.[1]

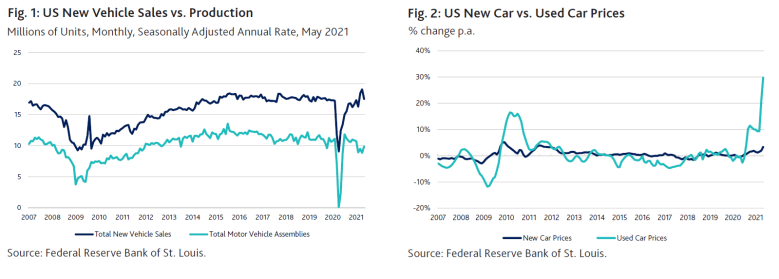

A most curious example of this phenomenon is evidenced in the US auto market, which is known for its endless supply of new vehicles. As new car sales reached the highest level recorded on a monthly basis since the global financial crisis (GFC) in April, production of new vehicles has simultaneously fallen to depressed levels as a result of component shortages (see Fig. 1). This has resulted in a 30% increase in the price of used cars and trucks over the past 12 months (see Fig. 2),[2] with stories that used cars are selling at levels well above the listed price for the same vehicle on the showroom floor!

So, is this the beginning of a new era where inflation heads higher and remains persistent? The argument that this is a temporary phenomenon caused by unusual circumstances generally rests on two key propositions. The first is that the supply/demand imbalances we are experiencing will be temporary, even if they take a year or two to resolve, and prices will fall back to where they were. We strongly agree with this proposition. If the economy is good at one thing, it is resolving shortages in the supply of goods and services. The second part of the argument, is that, as government spending winds back, economies will slow dramatically. As we have pointed out, this isn’t actually happening to date, and we don’t expect it will. Still, that would only suggest that it may take a little longer for prices to fall away.

The debate on inflation is quickly moving to the cost of labour. Despite high unemployment rates in most economies, employers are universally reporting that it is hard to fill roles. This is true not only in the developed world, but also in China. There is strong anecdotal evidence that wages are rising and it is expected that various measures of employment costs will post high numbers as the year progresses. There were some expectations that the roll back of government benefits would help ease wage cost pressure as more people returned to the labour force, but it’s not clear that this is happening. Time will tell.

However, the escalating cost of labour is not the concern that leads us to be wary about the re-emergence of inflation. Rather, it is the economic premise that if the rate of growth in money circulating in the economy is faster than the growth in the value of the economy’s output (i.e. nominal GDP) it will necessarily be inflationary. It is an idea that has long been out of fashion and ignored because it wasn’t apparently true.

Money printing post the GFC didn’t seem to create huge inflationary pressures, at least in the price of goods and services. This is partly because the excess growth in money supply (using aggregates such as M2 or M3) was quite timid. Additionally, inflation was only apparent in the price of assets such as property and shares – not goods and services. In the past 12 months in the US, the printing of money has been prodigious and there has been inflation not only in assets, with residential property prices up 15% over the year to June[3] and the stock market up strongly, but now also in the CPI, with some of the highest numbers recorded in decades.

As fiscal spending initiatives roll off, the printing presses will slow. What is not known though is what happens to the so-called velocity of money (or more simply, how often money is spent in a given period). Where households had received government payments and simply left them in the bank, this money was passive and had no influence on the financial system. Economists would view this as driving down the velocity of money. As economies recover, if US households now elect to spend these savings over the next year or two, the velocity of money will start to recover and it remains possible that additional inflationary effects of the money printing last year could be experienced.

Does it really matter though if the Fed and other central banks keep interest rates at low levels?

It is important to appreciate that the role of central bank statements is not to tell us what they think is the likely course of interest rates, but to tell us what “they want us to believe” will be the likely course of interest rates. This is not quite as Machiavellian as it sounds. Central banks have rates set low for a reason and they want consumers and businesses to act as if they will stay low for the foreseeable future. When the central banks see the need to change, they will let us know, but the idea that they have the predictive powers to know that this will be sometime in 2023 or 2024 is insane. I think a far better premise for investors is that central banks will increase rates if it becomes clear that inflation is likely to be persistent.

Does it really matter if inflation is persistent? Why should the central banks respond at all?

Ultimately, the issue with inflation is that it represents a transfer of wealth between different groups in society. This is clearly seen in the discussion around the question of house affordability for first-time buyers that has been taking place in many countries. With goods and services inflation, the impact is usually felt mostly by lower-income households who struggle to put food on the table as prices rise faster than wages. Ultimately, workers will respond and demand higher wages, sparking a wage-price spiral. For this reason, inflation historically has been a serious problem for governments.

Even if central banks don’t respond initially to persistent inflation, it is ultimately a political issue. The experience of the 1970s and 1980s was that, the longer it took for governments to respond to rising inflation, the longer and more persistent the problem became.

What does this all mean for markets?

After the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) Open Market Committee meeting in mid-June, where the comments post the meeting were interpreted as bringing forward the first rate increase from 2024 to 2023, the stock market’s reaction was curious. Investors returned to buying their favourite growth stocks and avoiding those more dependent on a good economic environment. This is an odd reaction, as a rate increase is literally years away (if we believe what the Fed tells us) and generally the economically sensitive stocks would be expected to perform well throughout the period of rising rates. This is quite possibly a reflex action by investors to return to perceived certainty (growth stocks and defensive businesses) at a time of uncertainty, rather than a statement that a possible rate increase in two years’ time will immediately stifle the economic recovery. This period is also coincident with a rise in concerns around the spread of the COVID Delta variant.

How will the China/West relations play into the market’s concerns?

The Group of Seven (G7)[4] meeting held in mid-June and celebrations of the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party in early July have brought the topic of China’s relationship with the West to the front pages of the newspapers once again. As we have discussed previously, the interdependence of our economic systems is a significant limiting factor on actions that can be taken by either side.

Certainly, statements from both sides in recent months appear to be more theatre for domestic politics than an intention of meaningful action. This is not to say there are not serious issues at stake here that need attention. When interviewed by the Financial Times, Armin Laschet, who is the current frontrunner to become Germany’s next chancellor, was quoted as saying, “The question is — if we’re talking about ‘restraining’ China, will that lead to a new conflict? Do we need a new adversary?” He also said “And there the European response was cautious, because, yes, China is a competitor and a systemic rival, it has a different model of society, but it’s also a partner, particularly in things like fighting climate change.”[5] This more nuanced approach to the issue of China relations is one that provides some small hope of resolving the current conflicts. In the meantime, the markets are treating the issue as a sideshow, which short of some dramatic developments, it probably is.

Finally, the issue of the anti-monopoly movement continues in the background. In China, action has been taken in regulating areas such as fintech and anti-competitive behaviours in e-commerce. The approach in the West is clearly more process driven and will most likely be a drawn-out affair. In the US, President Biden appointed Lina Kahn, a high-profile academic who has argued for a reframing of US competition laws, to chair the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). This is a pretty clear statement of intent. In the short term though, the FTC case against Facebook has been dismissed. We expect this movement to be a feature of the investment environment for the large e-commerce and payments businesses around the globe.

The outlook for markets?

In this overview, we have focused on a number of negative elements in the current investment environment. However, the one real positive is the strength of the global economy coming out of the 2020 recession. Generally, one would expect this to be a good time to own shares. Certainly, there are many companies that we hold across our portfolios that we expect will likely benefit from the recovery and still trade at reasonable valuations.

While there are reasons to be optimistic about stock market returns, there are obvious areas of concern, notably the risk of persistently high levels of inflation and the impact on interest rates. It is not a definitive prediction but a reason to remain wary, particularly for investors in the highly favoured growth stocks trading at extremely high valuations.

ENDNOTES

[1] Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[2] Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

[3] As measured by the S&P Case-Shiller National Home Price Index. Source: FactSet Research Systems.

[4] The G7 includes Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States.

[5] Source: Financial Times, 21 June 2021.

DISCLAIMER: This article has been prepared by Platinum Investment Management Limited ABN 25 063 565 006, AFSL 221935, trading as Platinum Asset Management (“Platinum”). This information is general in nature and does not take into account your specific needs or circumstances. You should consider your own financial position, objectives and requirements and seek professional financial advice before making any financial decisions. You should also read the relevant product disclosure statement before making any decision to acquire units in any of our funds, copies are available at www.platinum.com.au. The commentary reflects Platinum’s views and beliefs at the time of preparation, which are subject to change without notice. No representations or warranties are made by Platinum as to their accuracy or reliability. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by Platinum for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information.

MSCI Disclaimer: The MSCI information may only be used for your internal use, may not be reproduced or redisseminated in any form and may not be used as a basis for or a component of any financial instruments or products or indices. None of the MSCI information is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such. Historical data and analysis should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of any future performance analysis, forecast or prediction. The MSCI information is provided on an “as is” basis and the user of this information assumes the entire risk of any use made of this information. MSCI, each of its affiliates and each other person involved in or related to compiling, computing or creating any MSCI information (collectively, the “MSCI Parties”) expressly disclaims all warranties (including, without limitation, any warranties of originality, accuracy, completeness, timeliness, non-infringement, merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose) with respect to this information. Without limiting any of the foregoing, in no event shall any MSCI Party have any liability for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, punitive, consequential (including, without limitation, lost profits) or any other damages. (www.msci.com)