Introduction

It sometimes seems that the worry list for investors has become more threatening and more confusing than ever. This was an issue prior to coronavirus – with trade wars, President Trump, social polarisation, tensions with China, concerns the Eurozone would break apart, slow growth in Australia, and ever-present predictions of a new global financial collapse. Coronavirus has only added to the worries with hourly updates about new cases, lockdowns, vaccines, etc. It sometimes seems that if coronavirus won’t get us, inflation and the mountain of debt will. To be sure these risks are real and can’t be ignored, but the risks around investing seem to receive ever higher prominence these days as the digital age enables the rapid dissemination of news and opinion. The danger is that all this noise is making us worse investors as we lurch from one worry to the next. The key to investor success is to manage the noise and stay focussed. This is an update of a note I wrote a few years ago but the need to turn down the noise is more important than ever.

Ever more worrying worries

While there’s no denying there are things to worry about, there is a psychological aspect to this that is combining with the increasing availability of information, and intensifying competition amongst different forms of media for clicks, which is magnifying perceptions around various worries.

Firstly, our brains are wired in a way that makes us natural receptors of bad news. People suffer from a behavioural trait that has become known as “loss aversion” in that a loss in financial wealth is felt much more distastefully than the beneficial impact of the same sized gain. This probably reflects the evolution of the human brain in the Pleistocene age when the key was to avoid being eaten by a sabre-toothed tiger or squashed by a wholly mammoth. This leaves us biased to be more risk averse and it also leaves us more predisposed to bad news stories as opposed to good. Consequently, bad news and doom and gloom find a more ready market than good news or balanced commentary as it appeals to our instinct to look for risks. So “bad news and pessimism sells”. Flowing from this, prognosticators of gloom are more likely to be revered as deep thinkers than optimists. As Joseph Schumpeter observed “pessimistic visions about anything usually strike the public as more erudite than optimistic ones.”

Secondly, we are now exposed to more information than ever on how our investments are going and everything else. We can now check facts, analyse things, sound informed easier than ever. But for the most part we have no way of weighing such information and no time to do so. So, it becomes noise. As Frank Zappa (and maybe some others) noted “Information is not knowledge, knowledge is not wisdom.” This comes with a cost for investors. If we don’t have a process to filter it and focus on what matters, we can suffer from information overload. This can be bad for investors as when faced with more (and often bad) news we can freeze up and make the wrong decisions with our investment. In particular our natural “loss aversion” can combine with what is called the “recency bias” – that sees people give more weight to recent events in assessing the future – to see investors project recent bad news into the future and so sell after a fall. A 1997 study by US behavioural economist Richard Thaler and others showed that providing investors in an experiment “with frequent feedback about their [investment] outcome is likely to encourage their worst tendencies…More is not always better. The subjects with the most data did the worst in terms of money earned.” As famed investor Peter Lynch observed “Stock market news has gone from hard to find (in the 1970s and early 1980s), then easy to find (in the late 1980s), then hard to get away from.”

Thirdly, there is an explosion in media outlets all competing for our eyes and ears. We are now bombarded with economic and financial news and opinions with 24/7 coverage by multiple web sites, subscription services, finance updates, dedicated TV and online channels, chat rooms, individuals’ comments via social media, etc. And, following from loss aversion, in competing for your attention, bad news and gloom naturally trumps good news and balanced commentary. So naturally it seems that the bad news is “badder” and the worries more worrying than ever.

I Googled the words “the coming financial crisis” recently and found 352 million search results with titles such as:

- “brace for the next crisis”;

- “stimulus spending could cause the next economic crash”;

- “cryptocurrencies will lead the next financial crisis”;

- “a new crisis is ahead – can you survive it?”.

In the pre-social media/pre-internet days it was much harder for ordinary investors to be exposed to such disaster stories on a regular basis. The danger is that the combination of a massive ramp up in information and opinion, combined with our natural inclination to zoom in on negative news, is making us worse investors: more distracted, fearful, jittery and short-term focussed, and less reflective and long-term focussed.

Five ways to manage information & opinion overload

To be a successful investor you need to make the most of the power of compound interest and to do that you need to invest for the long-term in assets that grow with the economy and not get blown around by each new worry and fad. The only way to do this is to turn down the noise on the worry list and the explosion in investment information and opinion. This is getting harder given the distractions on social media. At an obvious level, it makes sense to turn off all notifications on your phone or iPad, but more fundamentally, here are five suggestions as to how to turn down the noise and stay focussed as an investor:

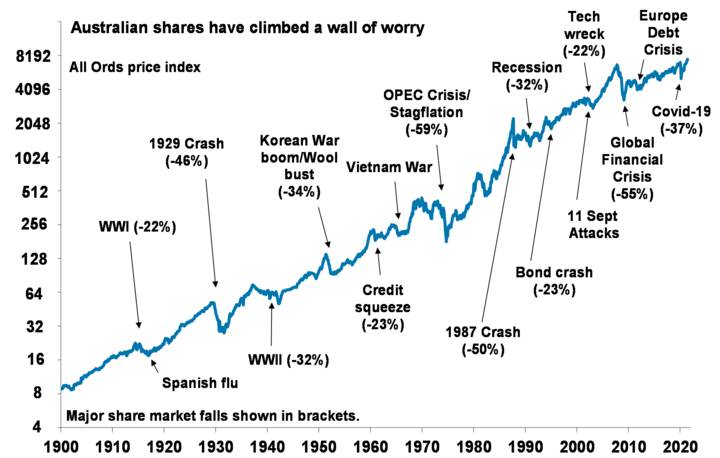

Firstly, put the latest worry in context. There’s always been an endless stream of worries. Here’s a partial list since 1900: 1906 San Francisco earthquake; 1907 US financial panic; WWI; 1918 Spanish flu pandemic (up to 50 million killed); The Great Depression; WW2; Korean War; 1957 flu pandemic; 1960 credit crunch; Cuban missile crisis; Vietnam War; 1968 flu pandemic; 1973 OPEC oil embargo; Watergate; the cancellation of The Brady Bunch; stagflation in the 1970s; the 1979 oil crisis; Latin American debt crisis; Chernobyl disaster; 1987 crash; First Gulf War; Japanese bubble economy collapse; US Savings & Loan crisis; Asian crisis; Tech wreck; 9/11 terrorist attacks; Second Gulf War; the GFC; the Eurozone public debt crisis; US trade wars; President Trump; & the coronavirus pandemic. But despite this investment returns have actually been good as shares climb a long-term wall of worry with the result being that since 1900 Australian shares have returned 11.8% pa and US shares 10% pa (including capital growth and dividends).

Source: ASX, AMP Capital

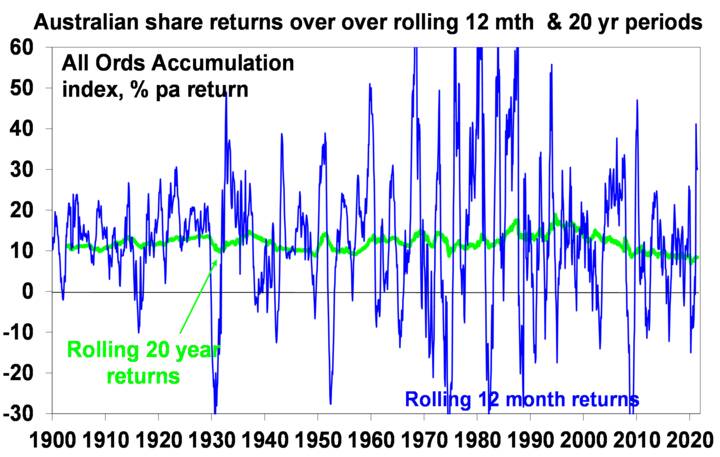

Secondly, recognise how markets work. A diverse portfolio of shares returns more than bonds and cash long term because it can lose money short term. As seen in the chart below, while the share market can be highly volatile in the short-term it has strong returns over all rolling 20-year periods.

Source: ASX, AMP Capital

And invariably the short-term volatility is driven by investors projecting recent events around profits, dividends, rents and interest rates into the future, and so, causing shares to periodically diverge from long-term fundamental value. So, share market volatility driven by worries, bad news, and bouts of recovery and investor euphoria is normal. It’s the price investors pay for higher longer-term returns.

Thirdly, find a way to filter news so that it doesn’t distort your investment decisions. There are lots of ways to do this depending on how much you want to be involved in managing your investments. If you want to be heavily involved it could mean building your own investment process or choosing 1-3 good investment subscription services and relying on them. Or simpler still, agreeing to a long-term strategy with a financial planner and sticking to it.

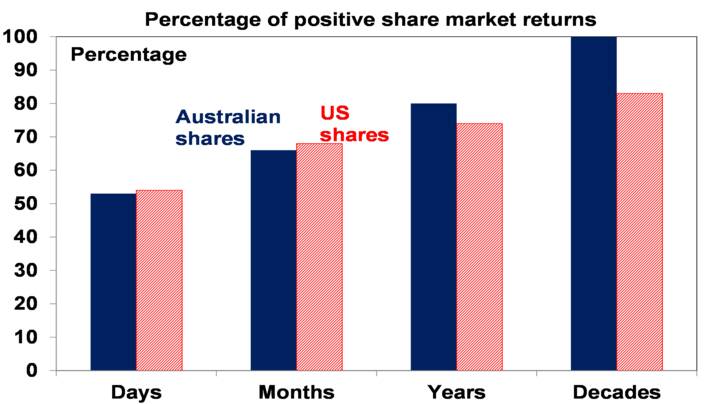

Fourthly, don’t check your investments so much. If you track the daily movements in the Australian All Ords price index, measured over the last twenty-five years or so it has been down almost as much as it has been up (see the next chart). It’s little different for the US S&P 500. So, each day is pretty much a coin toss as to whether you will get good news or bad as markets are thrown around by the daily noise. By contrast, if you only look at how the share market has gone each month and allow for dividends, historical experience tells us you will get bad news less than 35% of the time. Looking only on a calendar year basis, data back to 1900 indicates that the probability of bad news in the form of a loss slides further to just 20% of the time for Australian shares and less than 30% for US shares. And if you can stretch it out to once a decade, again since 1900, positive returns have been seen 100% of the time for Australian shares and 82% of the time for US shares.

Daily and monthly data from 1995. Data for years and decades from 1900. Source: ASX, AMP Capital

The less frequently you look the less you will be disappointed, and so, the lower the chance that a bout of “loss aversion” will be triggered which leads you to sell at the wrong time. So, try to avoid looking at market updates so regularly and even consider removing related apps from your smartphones & tablets.

Finally, look for opportunities that bad news and investor worries throw up. Always remember that periods of share market turbulence after bad news throw up opportunities for investors as such periods push shares into cheap territory from which strong gains have historically been seen. This is exactly what we saw last year at the height of coronavirus uncertainty.

Concluding comment

There is no denying that things occasionally go wrong weighing on investment returns. But predictions of imminent disaster are a dime a dozen. My long-term experience around investing tells me it’s far more productive to push against prognostications of financial gloom because most of the time they are wrong and end up just distracting investors from their goals.