Described as the ‘glue’ for electrification, tin connects all elements of electronic devices whilst enabling the free movement of electrons, making it essential to the foundation of many electronic components.

And with the continual fast-paced growth of electronics – including renewable energy devices and the geopolitical weapon that is semiconductor chips – tin will be a fundamental piece in ensuring the future reliability and performance of such devices.

Despite which, with the likes of lithium, cobalt, and rare earths dominating electrification moving forward, tin has been forgotten.

And this lack of popularity on an international scale has been reflected by the poor performances of many global tin producers.

Cornish Metals (CVE: CUSN), Andrada Mining (LON: ATM) and Yunnan Tin Co (SHE: 000960) have seen their share price fall by 45%, 20% and 8.5% respectively since June 1, 2022.

Whilst one of the biggest tin companies in the world, P.T. Timah (IDX: TINS), operating in Indonesia, has seen their share price drop by almost 40% since the same date.

A lot of this might have to do with a mis- or lack of understanding with regard to tin, its availability, properties and uses.

Tin is a silvery-white, soft, and malleable metal that is widely used in many industries for its properties of corrosion resistance and solderability.

It is relatively abundant, with most of the global production coming from China, Indonesia, Myanmar (formerly Burma), Peru, DRC, Russia, and Australia.

It is widely used in a variety of applications due to its unique properties, including corrosion resistance, low toxicity, and the ability to easily form alloys with other metals.

It also has many traditional and historic uses, such as the humble tin, and its use in pewter, a soft metal alloy used to make household items such as plates, cups, and candlesticks.

Currently, its biggest application is in solder, which is a material used to join two metal surfaces together, making it ideal for use in electronic components and other applications where precision and reliability are important.

Traditionally, solder was a Lead-tin based blend, with the majority of the mix being made up of lead. However, due to the toxicity of lead, tin has replaced it, with the current mix being roughly 95% tin and 5% silver.

Nowadays, this tin-based solder serves a massive purpose in the renewable energy movement and in the manufacturing of semi-conductor chips.

For an electric vehicle battery, solder is used to connect individual battery cells within a battery pack, ensuring a strong and reliable electrical connection. It also encapsulates the battery cells, providing protection against environmental factors such as moisture and temperature changes.

For solar panels, tin-based solder is used in photovoltaic (PV) cells and modules to join metal components and provide a strong, stable electrical connection between different parts of the solar panel, whilst also acting as a coating material to protect the solar panel’s metal parts against environmental factors such as moisture and temperature changes.

Solder’s protection against corrosion is also why it is used in the make-up of wind turbines.

And in regard to its usage in semiconductor chips, tin is used to form thin films or plating on the surface of the semiconductor material to enhance the electrical and thermal performance of the device, whilst also being used for interconnects and bonding pads in semiconductor devices.

By using solder in the construction of these products, manufacturers can ensure that these are reliable, safe, and able to perform effectively over time.

So why hasn’t it become as popular as the other commodities used to make these devices?

There are several potential reasons for this.

Firstly, tin mining can be challenging.

Tin deposits are often associated with complex geological formations, making extraction difficult and requiring specialized knowledge and expertise. In addition, many of the easily accessible tin deposits have been depleted, and new deposits are typically located in remote and challenging environments.

Tin mining can also face environmental and social challenges, including deforestation, soil erosion, water pollution, and human rights abuses, which can make tin less attractive to consumers and investors.

However, the main reason probably aligns with the fact that tin is not used in the production of the actual batteries themselves. Instead, the main components of an EV battery are typically lithium cobalt, nickel, graphite, manganese, and copper, which are metals with high redox potentials that are well suited for battery operation.

Tin, while a useful metal in many applications, does not have the necessary electrochemical properties for use in batteries.

However, ignoring its lack of flair and popularity, Tin will be a fundamental piece in the electronic space moving forward. Which may explain why its price has soared by 80% since June 2022.

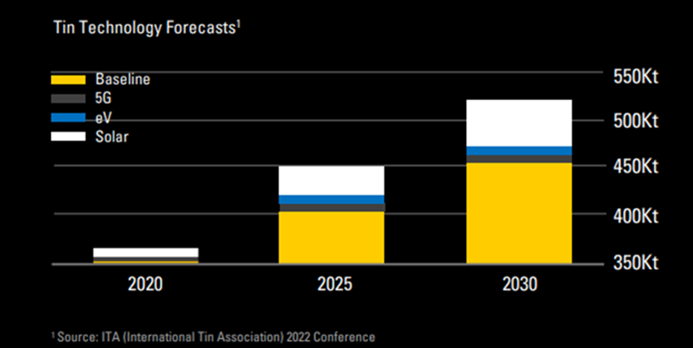

And whilst Tin doesn’t have the projection figures of graphite or lithium, it is growing 2-3 times its historical average, with the breakdown of forecasts projected in the image below.

In addition, both the recent abandonment of China’s COVID-lockdowns and the U.S. Federal Reserve’s hinting at a slowdown in the pace of interest rate rises have caused this spike in the price of tin, along with several other commodities such as zinc and copper. A softening in the US dollar, which importers use to buy commodities, has further exacerbated matters to the point that the prices of this group of base metals have surged more than 20 per cent in the past three months alone. Tin was the superstar of the bunch however, seeing an increase in its price by 65.5% over that period.

And the space is particularly exciting in Australia, especially when – as seems to be an almost universal theme at present – more countries are looking to localise supply chains and stray away from countries such as China, Myanmar (formerly Burma), DRC and Russia with elevated sovereign or geopolitical risk.

Several Australian companies are on track to solve these very issues.

Elementos (ASX: ELE) with its flagship, open-cut Oropesa Tin Project in Spain, which is one of the largest underdeveloped projects in the world, taps into a European landscape that has openly stated that they are looking to localise supply chains within the Eurozone to feed their manufacturing of renewable devices.

Australia’s largest tin producer Metals X (ASX: MLX), which has a 50% interest in the Renison Tin Operation in Tasmania, one of the highest-grade tin mines in the world. The company also holds a 50% stake in the Renison Tailings Retreatment Project, aimed at producing 22.5 million tonnes of tailings at an average grade of 0.44% tin.

And finally, European Metals (ASX: EMH), hosts the largest lithium resource in Europe, and one of the largest undeveloped tin resources in the world – The Cinovec Project. The project is located in the Central Europe, providing convenient access to end-user automobile manufacturers and energy storage companies.

No doubt tin’s versatility has allowed it transition into the modern era smoothly, acting as the ‘salt and pepper’ of the shift toward electrification and becoming essential to the manufacture of renewable devices and semiconductor chips.

As the transition to clean energy accelerates, and with major regions like Europe and the USA looking to diversify from Chinese supply chains, the tin sector in Australia presents a significant opportunity to support these shifts.