Though I watch cash investments closely, it was a shock to see the article in The Australian recently exposing the practice of classifying asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities, commercial bonds, hybrids, credit default swaps, loans and other credit instruments as ‘cash’.

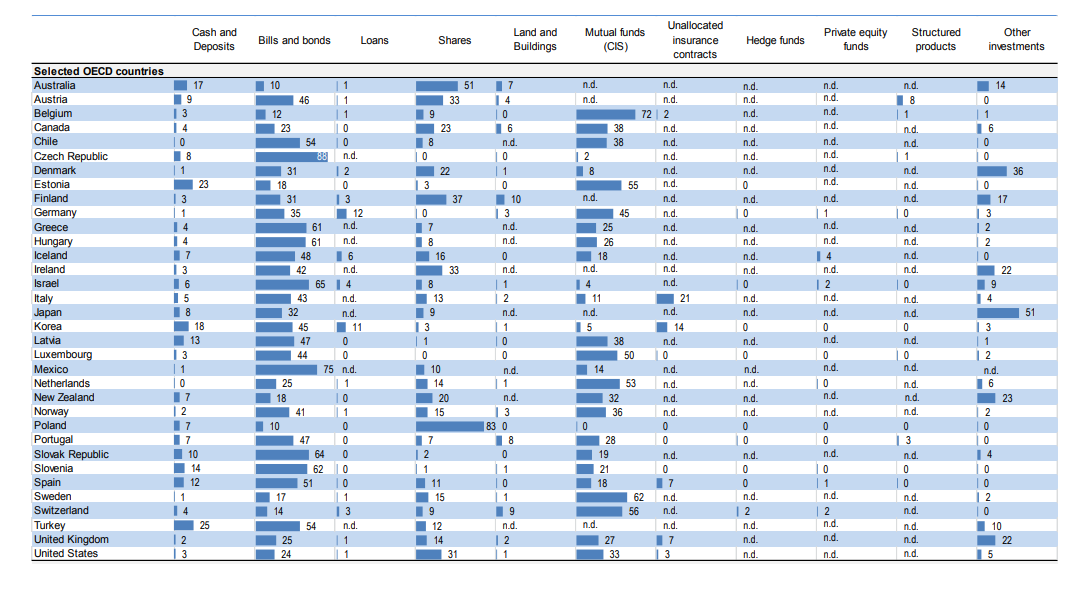

Put simply, this practice makes some funds more riskier than they look. According to the OECD, Australian superannuation funds are already some of the most risky in the developed world, investing some of the highest percentages in shares at 51 per cent and offsetting some of the risk with high cash holdings of 17 per cent.

But what we know is that in some cases – even among the biggest and best known funds – the cash isn’t really cash.

We need some clarity about who the culprits are, how widespread the practice is and how APRA propose to remedy the situation and ensure future compliance.

The Australian superannuation system is different to others in the OECD and is mostly ‘defined contribution’, with the only certainty being how much you put in.

Australian superannuation providers take virtually no risk, unlike superannuation funds in other countries where systems are ‘defined benefit’ and providers are obliged to provide certain cashflows on retirement. Success in these countries is more aligned to funds being available to meet future obligations rather than historic returns.

Defined benefit funds have a long term view and aim to maximise the value of the fund for the member at retirement, while being cognisant of preserving capital. They prefer more consistent, lower risk assets to meet those obligations and typically have significant holdings in bills and bonds, averaging 40 per cent of portfolio allocation.

Australian superannuation funds are desperately underweight this asset class and joint last of 34 OECD countries with Poland, holding an allocation of just 10 per cent.

Without the need to think about providing long term retirement funding and instead being driven by short term returns, Australian superannuation funds take on too much risk. It’s the members of the fund, that are not necessarily financially savvy that take the risk.

They largely rely on superannuation institutions to do the right thing, make the best decisions on their behalf.

The same issue confronts private investors reacting to advertisements for so-called cash rates which on closer inspection turn out to be a mixture of cash and products which can be quite a distance from what might be usually considered as cash, such as first mortgage income.

Unfortunately, the main and perhaps only qualification members seek is returns, compelling domestic superannuation funds to invest a greater proportion in the highest yielding but highest risk assets, shares.

Dangerous territory. Just ask someone that retired just prior to the GFC and had their “comfortable” retirement decimated by a major market dislocation.

Superannuation asset allocation needs to change over the investor’s lifecycle and become much more defensive near and into retirement. Providers should be increasing allocations to defensive assets, rather than exposing unsuspecting member funds to additional risk and notional higher returns to attract more members.

One last thing: investors who are unwittingly in these cash like products might take heed of APRA’s definition of cash under Superannuation Reporting Standard (SRS) 530 Investments, which states that “cash” represents cash on hand and demand deposits, as well as cash equivalents.

“Cash equivalents represent short-term, highly liquid investments that are readily convertible to known amounts of cash and which are subject to an insignificant risk of changes in value”.

That cannot be said of hybrids – the highest risk asset on the list of ‘cash equivalents’. They are not short term even if acquired within a year to first call, as there is no guarantee of conversion or redemption and in fact some are perpetual instruments with no repayment obligations. They are certainly not highly liquid. Instead, they are at times illiquid and at risk of significant changes in value of up to 30 per cent if you take the GFC as an example.

Cash is cash on hand – at call – money you or your fund manager can get at immediately. Anything else does not qualify.

Note: If you are interested in global pension fund asset class allocation, look up the ‘OECD Pension funds in focus 2017 report’.

OECD allocation of assets in funded and private pension arrangements, 2016 (% of total investment)

To view the full image, right click and select ‘Open image in a new tab’.

Source: http://www.oecd.org/pensions/private-pensions/Pension-Markets-in-Focus-2017.pdf, page 17